Fading Photos and Stories of Conflicts

An Interview with Emeric Lhuisset

Photography is a medium among many others I use. For my work on politics and human crisis, photography is the medium that (re)views reality.

Emeric Lhuisset

Emeric Lhuisset (*1983) grew up in the suburbs of Paris. He studied art at l’École nationale superièure des beaux-arts (ENSBA) in Paris and geopolitics at the University Panthéon-Sorbonne/École normale superièure. His work has been shown in several exhibitions and private collections worldwide (i.a. Tate Modern, Museum Folkwang, Institut du monde arabe, Stedelijk Museum, Sursock Museum, CRAC Languedoc-Roussillon, Musée de L’Armée, Kalfayan Galleries). Lhuisset was awarded many prizes (i.a. BMW Residency for Photography 2018, Grand Prix Images Vevey-Leica Prize 2017). He also published several books and participated in co-edited publications (i.a. “Quand les nuages parleront”, 2019). Emeric Lhuisset currently teaches contemporary art and geopolitics at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po).

As a photographer, artist and expert in geopolitics, Emeric Lhuisset has a remarkable understanding of human tragedies and areas of conflict. Through his projects in various areas of conflict he opposes the abridged representation of these tragedies; shows hidden aspects of wars; and invites us to re-think war through art. The work of Lhuisset takes up historical and political narratives in their context. The following two projects by Emeric Lhuisset recall tragedies and intervene in spaces where drastic events have taken place.

“I Heard the First Ring of My Death”

The journalist Sardasht Osman (1987-2010) was repeatedly threatened after he wrote an article criticizing the regional government of Kurdistan and the president of Iraqi Kurdistan, Massoud Barzani. His courage and persistence were stronger than fear. Sardasht Osman was kidnapped by gunmen outside the precincts of Salahaddin University in Erbil. He was later found dead in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul in May 2010 with bullets in his head. The fate of Sardasht Osman was a shock that caused dread and provoked questions. Many organizations condemned his murder, and mass demonstrations took place calling for an independent investigation and for the arrest of those involved. A year later, the Kurdistan Regional Government issued a short report claiming that the extremist group Ansar al-Islam killed Osman because he had not completed some promised work. The report did not confirm the allegation and was not considered credible.

Emeric Lhuisset was in Iraq for the first time in 2010 as a guest on the campus of Salahaddin University. Shortly afterwards, Sardasht Osman was abducted in front of the university. Since Lhuisset was almost the only foreigner on campus, many of Osman’s friends told him about the journalistic activities of their colleague in exposing corruption in local government. Osman’s last article was entitled “I heard the first ring of my death”, in which he mentioned the death threats he received to stop his investigations and critical reporting of local politicians and security officials. In this article Osman said that he would neither run away nor stop to write. He wanted to continue, even if the price would be his own life. These words touched Lhuisset deep inside. When Sardasht Osman was found dead, Emeric Lhuisset was deeply shocked and felt the need to do something to pay tribute to Sardasht Osman.

I was the only foreigner on that campus located in a pacified area. I was trusted by students who approached me and told me about Saradasht: his activism and his articles. I was emotionally taken by the news of his death. He was almost the same age of my younger brother. I witnessed the aftermath of what happened, and I could not remain an observer. Being an artist gives you access to the public, which is also your responsibility at the same time.

Emeric Lhuisset

He worked closely and intensively with Osman’s family, who gave Lhuisset a small portrait of their late beloved son. Back in France he scanned the portrait to make larger photographs on unfixed salted paper. These pictures had to wait one year before they could fly to Iraq. On the first anniversary of Sardasht Osman’s murder Lhuisset put the salty paper pictures with Osman’s portrait on the walls in the dark streets before sunrise. Sardasht Osman’s face was the first thing people saw when they came out of their houses in the morning.

Photo: Emeric Lhuisset © with courtesy

Photo: Emeric Lhuisset © with courtesy

The portraits of Sardasht Osman were transformed into time-based installations distributed in the urban space to commemorate the journalist and his fate. Sardasht Osman used to publish invisibly under a pseudonym, and through Emeric Lhuisset’s work the absence of Osman had a new nuance. The work wanted to occupy the spaces of the city where Sardasht Osman lived, raised his voice, and died. The unfixed salted paper photographs gradually faded and disappeared in direct sunlight, leaving black memorials in their place. An allegory of an unsolved murder for which no one was prosecuted.

“L’autre rive” (The Other Shoreline)

Conflicts not only cause the disappearance of people and death. Wars also uproot and change lives. Lhuisset tackles with the – generally mistaken – discourse on refugees, a discourse that is often reduced to three misrepresentations. The first interpretation shows refugees through snapshots detached from the context (arrests, walls, dead bodies on the beach …). The second one is an oversimplified accusation that connects all the problems of the host societies with the refugees and spreads a manipulative fear. The third misrepresentation is an oversimplified one, which often shows refugees as poor and miserable.

Emeric Lhuisset did not only want to show photos and tell stories about the refugees. He wanted to experience what most of them have been through. What could be more challenging than crossing a barbed wire fence at the border? After two failed attempts, accompanied by gunfire, Lhuisset crossed the border between Syria and Turkey. There is too much complexity between one step before and another one after the barbed wire fence. Before crossing the border one is faced by death and by the fear of what is coming. After crossing the border, fear persists with the beginning of a new destiny: the life as a refugee. Either on the land or on the sea there is another shore.

Photo: Emeric Lhuisset © with courtesy

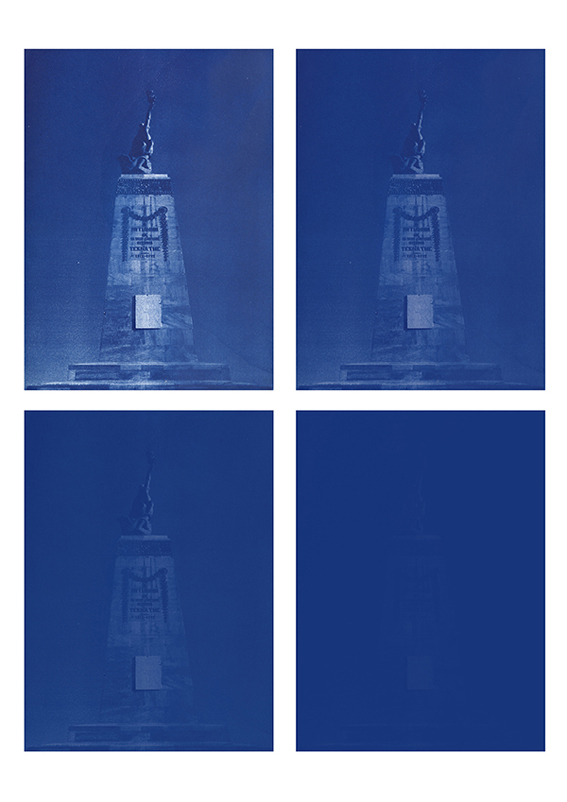

The bronze Statue of Liberty at the harbor of Mytilene on the Greek island of Lesbos was created by Greek sculptor Gregorios Zevgolis after a design by the local painter Georgios Jakobides. The statue was cast in Germany in the 1920s to commemorate the victims of WWI and then erected in 1930. It is the site of the annual commemoration of the Greek Revolution on 25th March. The statue has become a landmark for many refugees. Inspired by the statue of New York, which has long been a symbol of the “American Dream”, the Statue of Lesbos has become for asylum seekers and refugees a symbol of the “European Dream”, and a nightmare at the same time.

The Greek island of Lesbos has been in the headlines since 2015. Because of its proximity to the Turkish mainland, Lesbos is the first shore that refugees and asylum seekers reach (or try to reach) on their way to Europe. After working in many war zones, Lhuisset made many friends in Iraq, Syria or Afghanistan with whom he remained in contact. Some of them decided to move to Europe, risking their lives. He followed their journey through messages. Some came to Europe, others never did.

Emeric Lhuisset remembers the stories of his grandmother’s journey to North Africa (Tunisia) when she left war-ravaged Europe. The same kind of tragedies have occurred again and again throughout history, and Lhuisset wanted to work for remembrance.

Just look at how Europe evolved throughout history. One can simply notice that centuries of exchanges of ideas, peoples, languages and cultures have given Europe its real diversity and richness. The ”tissu provençal” illustrates this well: the Armenian refugees, who fled from the Cretan War, brought it with them to Marseille and introduced it to the local artisans. People migrate with their cultures, which they do not lose: they take from the new culture they encounter and in return they give back as well.

Emeric Lhuisset

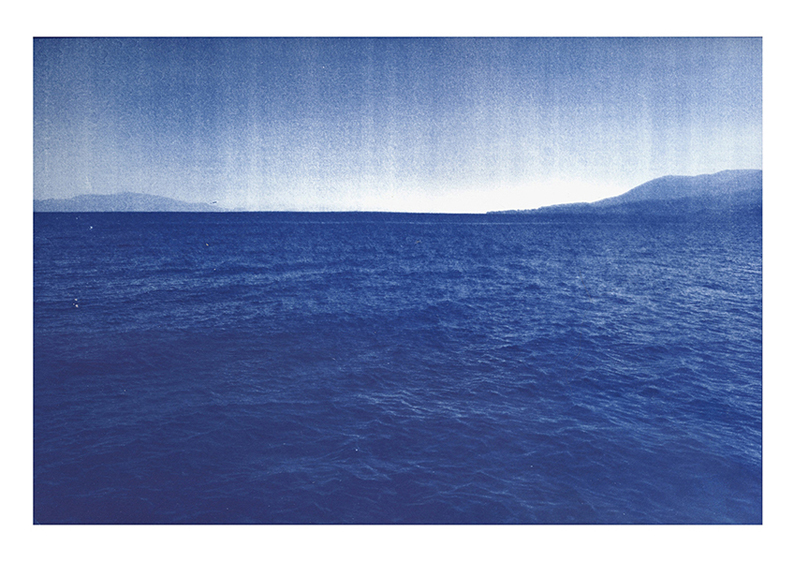

Cyanotype is a photographic printing process in which the images gradually fade after prolonged exposure to sunlight. This process results in a monochrome blue color palette. The project “L’autre rive” is a tribute to every person forced by the war to leave ”home” to seek refuge elsewhere. The non-fixed cyanotypes gradually fade to a monochrome blue. And this is the reality of refugees fate. Some disappeared in the blue color of the sea, while others reached their refuge under the blue flag of Europe to become part of it.

Photo: Emeric Lhuisset © with courtesy

Between the Turkish and Greek coasts, the tragedy of refugees and asylum seekers has turned the Mediterranean Sea since 2015 into a blue space of hope, fear and death.

The work of Emeric Lhuisset is a creative record of geopolitical examination. It invites us to question our view of events, their representation and their interpretation. Although art cannot necessarily affect political events, it can strongly influences the way we perceive them: through a new voice and new perspectives. Lhuisset understands his role as an artist as a responsibility to represent the tragedy of displacement and the horrors of wars. After all, photography tells stories.

Zitation

Zeina Elcheikh, Fading Photos and Stories of Conflicts. An Interview with Emeric Lhuisset, in: Visual History, 15.01.2020, https://www.visual-history.de/2020/01/15/fading-photos-and-stories-of-conflicts-emeric-lhuisset/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-1717

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Copyright (c) 2020 Clio-online e.V. und Autor*in, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online Projekts „Visual-History“ und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber*in vorliegt.

Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <bartlitz@zzf-potsdam.de>