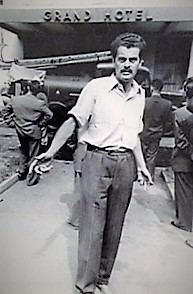

Friedrich Klinsky (1925-2002) Press Photographer

A visual search for traces

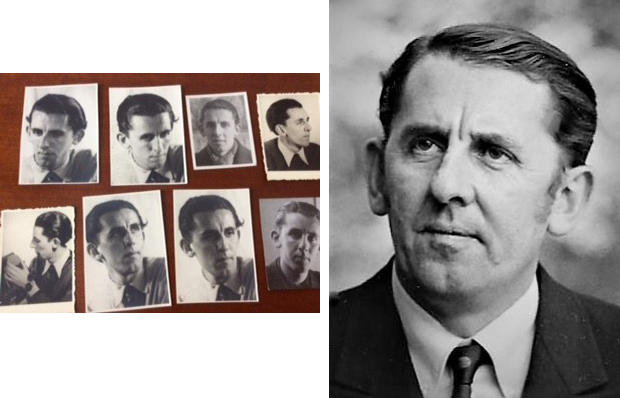

Fig. 1: Selected passport photos of Fritz Klinsky, Source: Private collection

My father was the press photographer Friedrich (“Fritz”) Klinsky. He was born in Vienna in 1925 and died there in 2002. At the age of ten, he became interested in photography. He was on the road with a cheap camera and developed the first pictures himself in his parents’ kitchen. He had been allowed to watch a photographer of a family friend. Due to the lack of financial resources he was denied an education at the Höhere Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt. At the age of 17, he began an apprenticeship as a photographer at the Gaulichtbildstelle of the National Socialist People’s Welfare (NSV), which he had to cut short after just one year due to a lung disease. After 1945 he succeeded in continuing his work as a photographer for various photo agencies as well as for the daily newspapers “Bild-Telegraph”, “Express”, “Kurier” and “Wochenpresse”. Friedrich Klinsky worked as a press photographer in Austria for forty years total, from 1946 until his retirement in 1984.

After his death, I began to follow the photographic traces my father left in his life. Basically, I would like to portray the life’s work, busyness, and uninterrupted mobility of this man – a photographer of the last century in the service of print media and integrated into a network of colleagues. Not surprisingly, the estate, which has so far only been incompletely catalogued, also contained photographs from a little-discussed past. In this article, I therefore present some of his photographs, which I will link with biographical stations in order to lay out an image mosaic for the first time. Future research by historians would be necessary in order to correctly place Friedrich Klinsky and his work in the history of press photography in Austria.

Fig. 2: “Gauhaus” of the Vienna NSDAP (the former parliament building) on Ringstrasse, Vienna 1939. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky ©, Source: Private collection

In March 1938, the so-called annexation of Austria to National Socialist Germany took place. The Klinsky family hardly talked about the early years after the annexation. According to his wife Franziska, shortly after the Anschluss in 1939 Fritz Klinsky, was detained by the Gestapo for one night at Morzinplatz in the notorious Hotel Métropole, which had become the Gestapo headquarters. He had photographed the sunset at the Reichsbrücke. In the evening, the Gestapo picked him up from his frightened mother, as it was suspected that he had taken up military matters.

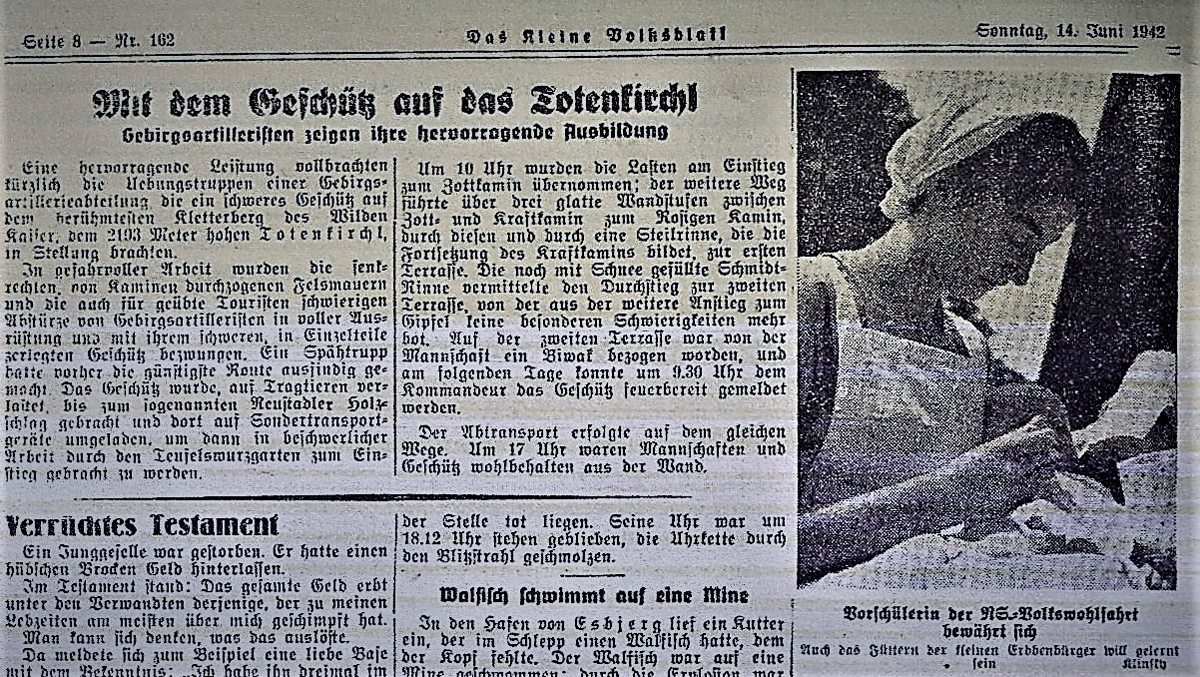

After dropping out of an apprenticeship as a radio technician, 17-year-old Friedrich Klinsky was offered the opportunity to work in the photo office of the National Socialist People’s Welfare. He described his employment as that of a “chancellery employee” and worked in the so-called Gaulichtbildstelle of the NS-Volkswohlfahrt, Vienna 1st district, Am Hof 6, under Alois Sedacek.

The NSV was a Nazi state organization that had the goal of “developing and promoting the vibrant, healthy forces of the German people,” as it was stated. [1] It was divided into six “offices”: organization, financial administration, welfare and youth welfare, public health, propaganda and training, and was mainly responsible for child and youth work during the war years.

Fig. 3: Photo: “Preschooler of the NS-Volkswohlfahrt proves herself. Even the feeding of the little earthlings needs to be learned.” Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky ©, in: “Das kleine Volksblatt”, 14 June 1943

Fig. 4: Erntedankfest Wien-Mödling, Festzug Eichkogel, 1942. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky © , Source: Private collection

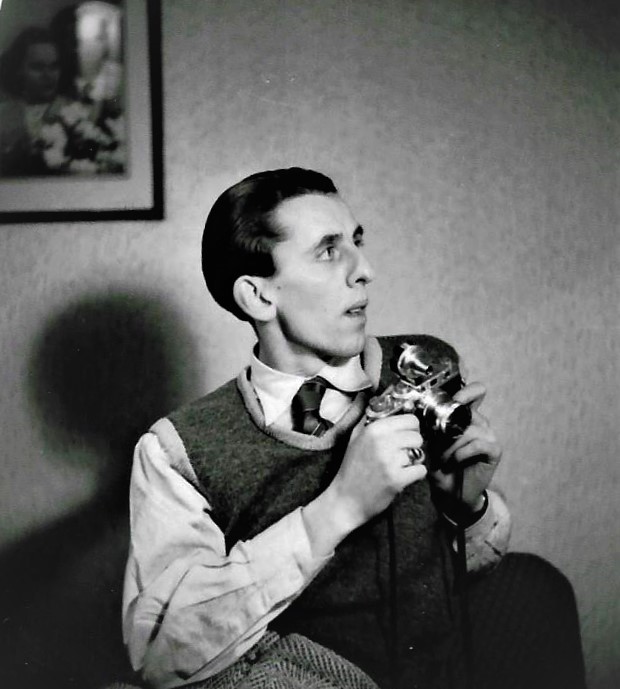

However, Friedrich Klinsky’s training at the NSV lasted only for a short time: 1943, a diagnosed lung disease led to an one-year stay in the so-called War Cure House for Lung Patients in Davos, Switzerland. He had already recovered and returned to Vienna, by then heavily fought over, when his mother died in an air raid in the autumn of 1944 during a visit to her sister in Vienna-Simmering. His father worked as a “Markör”(an old Austrian term for waiters) at an inn and often came home late at night. After the end of the war in 1945, his collaboration with the Wien-Bild agency (formerly Schostal, then “aryanized” and led by the Nazi Friedrich Gondos) and his lifelong friendship with photographers such as Harry Weber prove his will to enable himself to survive in difficult times through the medium of photography.

Fig. 5: A shot like a film still from a “Zauberberg” film adaptation: Fritz Klinsky (2nd from right) in the Kriegskurhaus für Lungenkranke in Davos, Switzerland, 1943. Negative 5.5 x 5.5 cm, photographer: unknown. Source: Private collection

Fig. 6: The young photographer in the 1940s. Negative 5.5 x 5.5 cm. Photographer: unknown, source: private collection

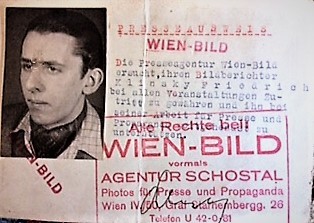

Fig. 7: Press card Wien-Bild, formerly Agentur Schostal, for the “Bildberichter Klinsky Friedrich”, undated, Source: Private collection

Friedrich Klinsky, not to be confused with Emilian Joseph Smetanic Klinsky (1899-1962), turned twenty in 1945. He began working as a press photographer in the destroyed city, which was divided into sectors, at the agency Wien-Bild, formerly press photo agency Schostal. [2] Founded by Robert Schostal in 1926, the agency had a collection of over one million photos, making it one of the leading agencies of the interwar period. [3] The company was represented in Paris, Milan, Stockholm, Warsaw and Berlin. But with the establishment of the Nazi regime, Jewish photo agencies were expropriated: From 1938, Friedrich Gondos provisonally led the Schostal agency , taking it over in September 1941 for a small purchase price. From then on, the press photo agency operated under the name Wien-Bild. Robert Schostal himself managed to escape to the USA, where he founded a new photo agency with his brothers.

Fig. 8: Photographer colleague Erhard Grandegger at the agency Wien-Bild, formerly Schostal, 1945. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky ©, Source: Private property of the Grandegger family

Friedrich Klinsky switched from Wien-Bild to other renowned agencies such as “Austrofot”[4] and Interpressphoto[5]. His work as a photographer at the nova-Press agency from 1946 to 1947 is documented through private papers. A portfolio [6] contains evidence of his photographic works from the “Wiener Bilderwoche”, the “Wiener Illustrierte”, the “Abend” and the “Weltpresse” from 1946 to1956, initially drawn with the agency Austrofot, then Nova-Press [7]. In 1947 “KLI”, as he was briefly called by fellow journalists, acquired a certificate of entitlement to own and operate a broadcast reception facility for his apartment in the Soviet sector to promptly receive information about current events.

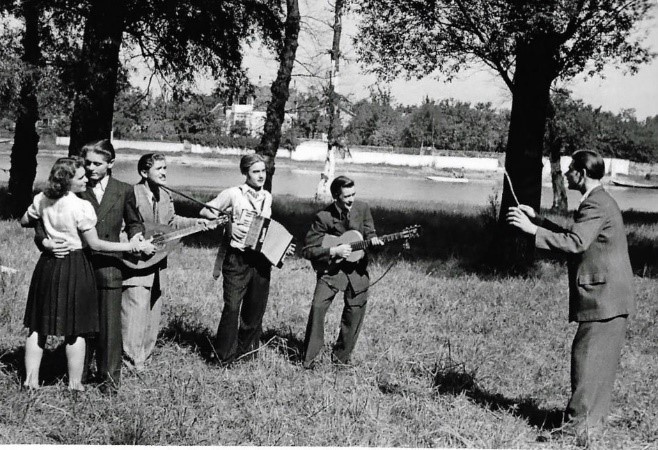

Fig. 9: Musicians in the Weissau in Kaisermühlen, 1940s. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky ©, Source: Private collection

Fig. 10: “Shuffling types” (“semi-strong”) in the Weissau in Kaisermühlen, 1940s. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky © , Source: Private collection

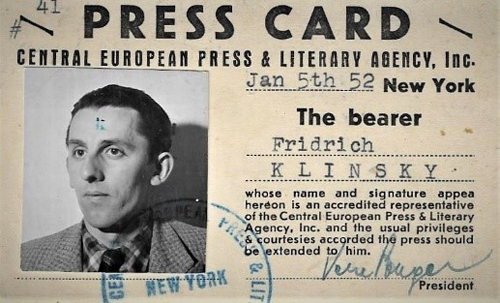

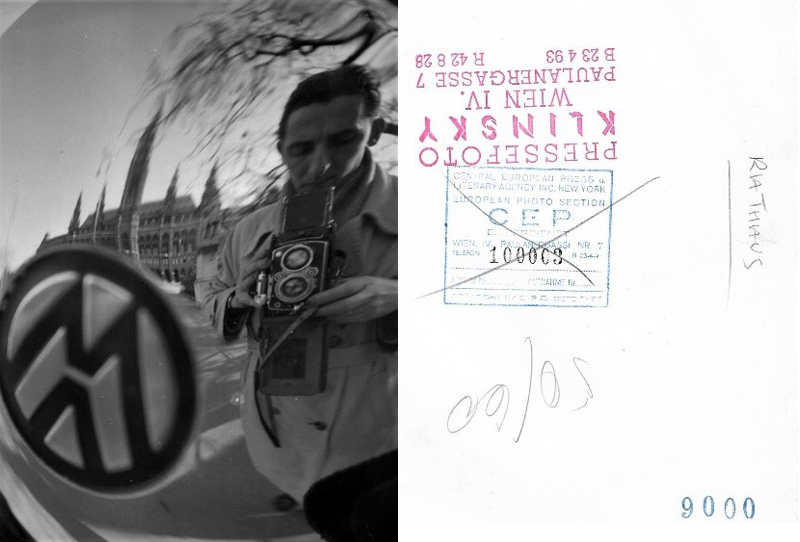

In a competition of the American Economic Cooperation Administration from 1950, a US office founded in 1948 to manage the funds of the Marshall Plan, Klinsky’s photograph of a coal mine was honored with a high prize money of 1500 shillings. The stamp “CEP – Bilderdienst” appears on the back of pictures from 1952 to 1955 handed down in the estate. This note is so far the only reference to a period of Friedrich Klinsky’s life with many open questions. The abbreviation stands for Central European Press & Literary Agency Inc. New York. The European representation of this agency – European Photo Section – was based in the Soviet sector of Vienna in the 4th district, Paulanergasse 7. The press card issued to him in January 1952 in New York proves that he worked for this agency, which was managed by Vera and Curt Ponger.

Fig. 11: Press card CEP 1952 for Fridrich [sic!] Klinsky, signed by Vera Ponger. Official address of the agency: 100 W 43nd Street New York, USA. Source: Private collection

Fig. 12: Self-portrait with Volkswagen in front of the Vienna City Hall, 1952, CEP. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky ©, Source: Private collection

Curt Ponger (1913-1979), born in Vienna to Jewish parents, was able to emigrate to the US via England in 1940 thanks to an affidavit of his future wife Vera Verber, but only after being detained at the concentration camps (in) Buchenwald (1938) and Dachau (1939). [8] Ponger, who was deployed as an interrogator for the Americans at the Nuremberg Trials against the main war criminals, was probably close to the communist youth organization of Austria in the 1930s, as was his wife Vera. In 1953, he was arrested on suspicion of espionage for the Soviet Union and sentenced to several years in prison in the United States. Curt Ponger did not return to Austria until the early 1960s.

Fig. 13: Kurt (Curt) Ponger (1913-1979), photographer: Friedrich Klinsky © , Source: Private collection

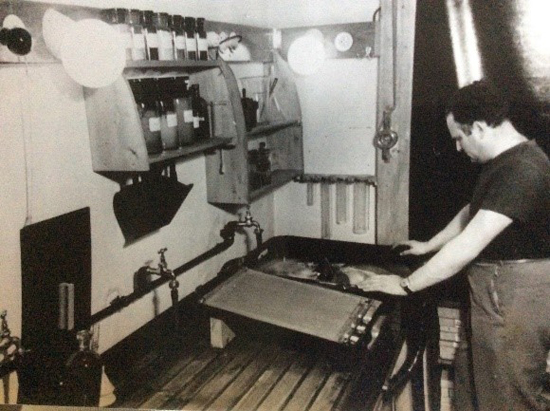

Fig. 14: Kurt (Curt) Ponger, 1952, in his laboratory in Vienna, at that time located in the Soviet sector, 4th district, Paulanergasse 7. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky © , Source: Private collection

To what extent Friedrich Klinsky as well as other employees of the CEP image service came into the focus of the CIA is not known to me. Likewise, I am not aware of the nature of his relationship with Curt and Vera Ponger. However, the existing pictures – especially ones of the children of the family – document a great familiarity with the couple before the arrest of Curt Ponger. Vera Ponger died of pneumonia in 1957 without seeing her husband again. Curt Ponger returned to Vienna after his release from prison and was appointed in 1970 as editor of the central organ of the Communist Party of Austria, “Volksstimme”, publishing mostly under his pseudonym “CUPO”.

Fig. 15: The Ponger kids, Vienna 1953. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky © , Source: Private collection

Fig. 16: Vera Ponger (3rd from left) with her daughter and friends. Vienna 1952. Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky © , Source: Private collection

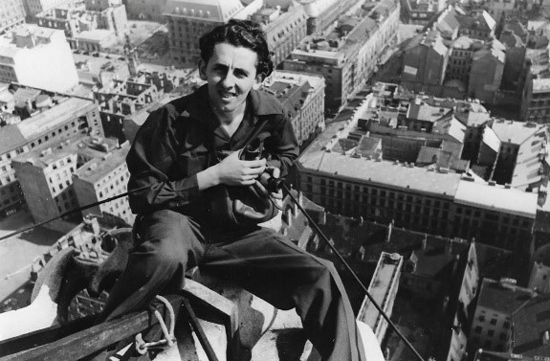

Fig. 17: Fritz Klinsky during photo session on the roof of St. Stephen’s Cathedral, unsecured, but wearingtrousers with crease, Vienna 1952, CEP. Photographer: unknown, Source: Private property

From 1953 Klinsky also worked as a photographer for the Fritz Kern Agency and a year later he became an active member of the Syndicate of Press Photographers, Press Photo Agencies and Film Reporters of Austria, which was founded in Vienna in 1947 and was the oldest and most important professional interest group of Austrian press photographers. [9] Since 1955, Klinsky was able to establish himself as a press photographer for the tabloid “Bild-Telegraf”, founded in 1954. The newspaper was printed in the renowned Viennese press house on the Fleischmarkt, which had been leased by the editor Fritz Molden at the time. After the fierce journalistic and legal disputes of several publishers in the “Wiener Zeitungskrieg” in 1958, Klinsky switched to the left-liberal “Express” under the editor-in-chief Gerd Bacher, who later became the general director at ORF.

Fig. 18: Cameramen and press photographers in 1961 at a reception of the Federal President with cameraman – “Mister Celluloid” – Hans Imber ( r. in a bright suit) Heinz Lazek, Ernst Kloss (4th from left), Fritz Kern (3rd from right), Fritz Klinsky (right) and others. Photo: Kristian Bissuti © courtesy, Source: Private collection

Fig. 19: The photographers Grandegger, Klinsky, Weber and others at Vienna Airport in the 1950s. Photographer: unknown, Source: Private collection

In order to increase the efficiency of image reporting, a “Press House Photo Pool” was established during this time, which included “Express” (with all three editions) as well as “Die Presse”, “Wochenpresse” and “Auto-Touring” and some weekly district newspapers. The overall organizational management of the pool was held by the journalist Dr. Emil Zálešák, who was responsible for adhering to a predetermined rotation service. The photographers Fritz Klinsky, Ernst Kloss and Fritz Mottl were intended for this purpose. Photographer and photojournalist Barbara Pflaum took over other ongoing assignments, which didn’t focus on actuality. [10] Together with Pflaum and her colleagues Fritz Schaler and Erst Kloss, Friedrich Klinsky was also involved in a photo group exhibition at the Vienna Konzerthaus in 1959. [11]

Fig. 20: Fritz Klinsky with Boxerhund, Fritz Mottl, Peter Lehner with Marianne Mottl and Erika Lehner as well as Harry Weber and Erhard Grandegger pose in front of Vienna’s downtown café Bobby, Seilergasse, in the 1950s. Photographer: unknown, Source: Private property

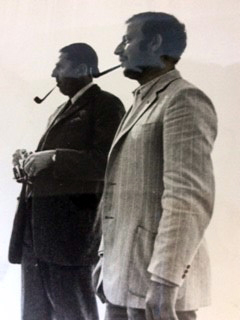

Fig. 21: Colleague Barbara Pflaum, Fritz Klinsky with pipe and Harry Weber (4 from left) and others Photo: Julius Büschel © Keystone Press Agency

While in May 1958 Fritz Molden decreed that photographers were entitled to resell their photos taken as part of their contract work to domestic and foreign newspapers – with the exclusion of all Viennese daily newspapers, the “province paper” “Salzburger Nachrichten” and all communist newspapers and magazines – Molden, in a letter from November 1958, threatened with “immediate dismissal” if photographers from the photo pool should pass on the pictures taken as special orders to other editorial offices. The “graphic staff” responded with passive resistance. [12]

Fig. 22: Press photographer Fritz Klinsky front left with flash, Vienna, March 1965. Photo: Barbara Pflaum ©, Source: Private collection

Fig. 23: Friedrich Klinsky with his long-time photographer colleague at the daily newspaper “Kurier”, Kristian Bissuti, from the 1970s. Photo: Kristian Bissuti © courtesy, Source: Private collection

Finally, Fritz Klinsky established himself as one of the leading photographers at the daily newspaper “Kurier”, for which he worked together with Gerhard Sokol, Kristian Bissuti, Fred Riedmann, Peter Lehner and Gabriela Brandenstein from 1960 to1977. The publishing house, at that time located in the 7th district between Seidengasse and Lindengasse, had integrated editorial offices, printing and administration. The photo reporters had a darkroom with an employed laboratory technician, to whom they usually passed on the exposed films in order to rush to the next appointment.

In addition to his always elegant clothing and his “trademark”, the pipe, Klinsky was known for his compact photographic equipment. He usually worked with Leica and Nikon cameras, which he carried with him in a small metal case. In addition to documentaries on domestic politics and major sporting events, such as the Winter Olympics in Innsbruck in 1964 and 1976, so-called foreign missions were also repeatedly on his schedule, such as in Hungary i1956 and in the CSSR 1968, or the documentation of devastating earthquakes such as the one in Skopje in 1963 and in Friuli in 1976. The mobility factor was extremely important to him. Since the 1940s, he had a moped, a motorcycle and later a large number of cars, which gave him quick access to the respective events with the press logo.

Fig. 24: The official press sign issued by the syndicate, source: private collection

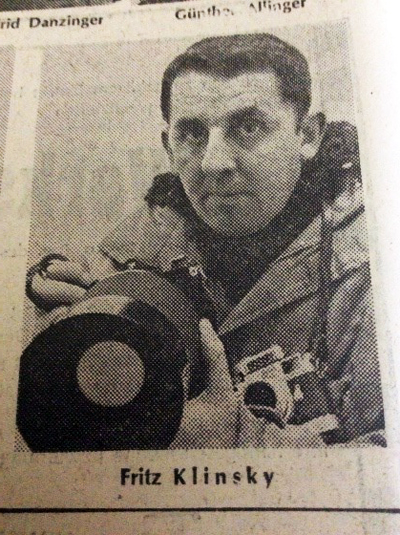

Fig. 25: Portrait “Fritz Klinsky”; Ein Bericht über das Kurier-Team bei der Winterolympiade Innsbruck 1964 von Günther Allinger Bleibt Deutsch?, in: Kurier, 1964

The “Kurier” presented the reporters of the 1964 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck to its readers in detail – including then 38-year-old Fritz Klinsky: “There is hardly a photographic problem that he would not be able to cope with. Whether it’s a smoky fire at midnight, a telephoto shot from a well-‘camouflaged’ hiding place, an atmospheric scene from a dark (lightning forbidden) courtroom. Or a sports situation that has to be captured in fractions of a second. There is hardly an international football match in which Fritz Klinsky would not lie ‘in wait’ behind a goal line with the camera. This time he will wait at the Olympic venues for the most favorable moment for his recordings, and each of his telegraphic images from Innsbruck will again convey ‘more than a thousand words’ to KURIER readers.” [13]

The Kurier editor Georg Markus also reported on this so-called telegraphic image transmission in retrospect and described it as “one of the most curious affairs in Austrian newspaper history”: In the province of Carinthia, after days of rainfall, flood alarms had prevailed and the state of emergency had been declared. “Federal President Franz Jonas had travelled to Klagenfurt, where he was received with all military honours on the square in front of the Lindwurm. It turned out that a harmless, but obviously not quite right-minded? guest saluted next to the Federal President, while he walked the parade. KURIER photographer Fritz Klinsky had captured the bizarre scene and reported to Vienna that the picture was traveling by telegraph?.”

Fig. 26: Curious affair about a photo showing Federal President Franz Jonas Photographer: Friedrich Klinsky ©, Source: Private collection

Editor-in-chief Hugo Portisch placed the photo on page one of the evening edition and commissioned a Viennese local editor to write the appropriate text. He wrote – without e having seen the picture – a few lines about the incident and put the title “A madman walks along at the parade.” A few minutes later, the picture transmitted from Carinthia arrived in Vienna. The photo laboratory assistant, who was not informed about the connections, had looked at the snapshot, recognized the Federal President and an unknown person, for whom, according to his assumption, no one would be interested anyway. Therefore, he had cut away the unknown man.

It was the first and only time in the history of the newspaper that the entire evening edition of the “Kurier” had to be stamped out. Because next to the title “A madman walks along at the parade “, the picture of the Austrian Federal President was displayed. [14]

Fig. 27: His two children preparing for Easter, Vienna 1966. Photographer: Fritz Klinsky ©, Source: Private collection

In addition to all these motifs from politics and society, the review of the surviving photographic material from the estate showed that the photographer Fritz Klinsky had preferred his family as actors for the execution of many commissions placed by the editors, such as in the symbolic image for Easter 1966.

Klinsky often showed solidarity with fellow photographers, as during the state visit of King Olav V to Schönbrunn Palace in 1966, where there was a scandal. After the head of the Federal Press Service had allowed the duly accredited Viennese press photographers to enter the State Hall, the newspaper people were thrown out again by other officials. These officials then put their cameras away and defiantly crossed their arms. The next day, the local newspapers reported the snub of the Norwegian monarch. [15]

Fig. 28: Photographers’ strike 1966, Schönbrunn Palace, on the right the photographers Eberhard Grandegger and Fritz Klinsky, in front of the picture the deposited photo equipment in front of the grandstand, Vienna 1966. Photographer: unknown, source: private collection

Fig. 29: Photo session with the family of Federal President Rudolf Kirchschläger, Fritz Klinsky left, Vienna 1974. Photo: Nora Schuster ©, Source: Private collection

With the change to the “Wochenpresse” in 1977, his area of responsibility changed, too: From now on, domestic politics and reports from the Viennese theaters again dominated his photographic work. The editor-in-chief Hans Magenschab and the head of the domestic policy department Gerald Freihofner provided the employed photographers Fritz Klinsky, Nora Schuster and Barbara Pflaum with a relatively pleasant working atmosphere. The photographers were expected to bring the already developed images to the editorial office for submission. In Klinsky’s house, a laboratory was set up in the so-called laundry room.

Fig. 30: Gunter Sachs, 1970, front and back. Photographer: Fritz Klinsky © Kurier

Fig. 31: “Kurier” front page on the 30th anniversary of the death of former Chancellor Bruno Kreisky, 2020, using a photo by Fritz Klinsky © / Kurier

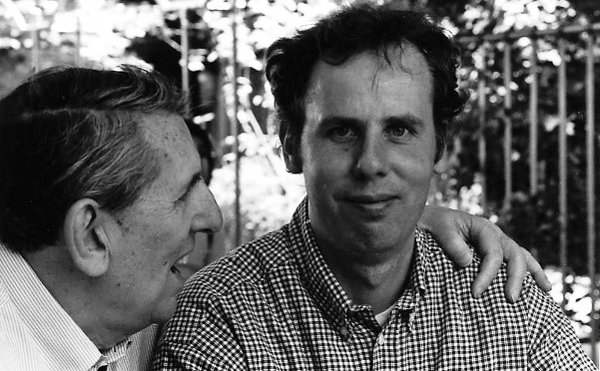

When Friedrich Klinsky retired in 1984, the profession of press photography began to change fundamentally. In addition to the emerging color photography, which increasingly displaced the classic black-and-white technique, photo technology evolved from analog to digital. Thus, actual darkroom work became obsolete: the classic craft, the “bathing of the images in the developer and fixer”,[16] which Klinsky had carried out early in the morning and late at night throughout his life, fell away. And cumbersome image transmissions from distant destinations using image telegraphy were also part of history in the new age of wireless communication. Friedrich Klinsky died in 2002 at the age of 77. Many years later, I began to trace back my father’s images.

Fig. 32: Friedrich and Alexander Klinsky, Augsburg 1998. Photo: Harry Weber © , Source private collection

The image archive of the Austrian National Library contains the estate of Friedrich Klinsky: a collection of about 20,000 photographs in 23 boxes, Leica negatives from the years 1961/62 and 1971/83, including photographs for the “Kurier” and the “Wochenpresse”, 22 folders (per volume about 100 titled slides with 24 black-and-white photographs in the format 24 x 36 mm) in rough chronology. Part of the collection is available digitally via the photo agency APA-PictureDesk [17]. The quality of his photos is evidenced, among other things, by his long-standing cooperation with the photo agencies Votava and Keystone Austria, whose representation was held by Julius Büschel.

[1] Cf. Herwart Vorländer, NS-Volkswohlfahrt und Winterhilfswerk des deutschen Volkes, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 34 (1986), H. 3, S. 341-380, hier S. 347f., online at https://www.ifz-muenchen.de/heftarchiv/1986_3_3_vorlaender.pdf [23.02.2022].

[2] Cf. Milena Greif, Agency Schostal. Mit den Fotos kehrt die Erinnerung zurück, in: Rundbrief Fotografie Bd. 9, Nr. 2 / N.F. 34, Juni 2002, , pp. 30-33.

[3] Cf. Anton Holzer, Rasende Reporter. Eine Kulturgeschichte des Fotojournalismus. Fotografie, Presse und Gesellschaft in Österreich 1890 bis 1945, Wien 2014, S. 241ff., online at https://e-book.fwf.ac.at/view/o:564 [22.02.2022].

[4] See the agreement between the company Austrofot, Vienna, 4th district, Schwindgasse 10, sole owner Wilhelm Nassau, with Friedrich Klinsky of 30.06.1946. End of employment 01.01.1947. Private property Alexander Klinsky.

[5] Interpressphoto – Photos for the domestic and foreign press, Eduard Zillich, Vienna, 1st district, Schulerstraße 19.

[6] This portfolio was in the domestic estate of Friedrich Klinsky and is now in the private possession of his son Alexander Klinsky.

[7] Nova-Press, press photo and sound reports, led by Hans Pfiffig and Gustav Gontard, Vienna, 7th district, Mariahilferstraße 118. Fritz Klinsky was employed there as a photo reporter from 1 July to 31 October 1947.

[8] See Vera (Verber) and Kurt (Curt) Ponger and others: Gaby Fahlböck, Narrative des Dazwischen. Writing in exile as identity-creating communication in the crisis carried out using the example of the Austrian exile magazine “Austro American Tribune”, undr. Phil. Dissertation, Vienna 2009, Chapter 5.2.3. “Vera Ponger”; Entry “Vera Ponger” in: biografia: biografische Datenbank und Lexikon österreichischer Frauen, http://biografia.sabiado.at/ponger-vera/ [22.02.2022]; “Chartered in Nuremberg”, in: Spiegel, 10.02.1953, online at https://www.spiegel.de/politik/in-nuernberg-gechartert-a-5e490bcd-0002-0001-0000-000025655788 [22.02.2022]; see also the CIA document of 7 January 1953 on the arrest, online at https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/KRICHBAUM,%20WILHELM_0024.pdf [22.02.2022].

[9] Cf. Marion Krammer/Margarethe Szeless, Berufsfeld Pressefotografie. Wettbewerb, Netzwerke und Bildkultur im besetzten Österreich 1945-1955, in: Matthias Karmasin/Christian Oggolder (eds.), Österreichische Mediengeschichte. Vol. 2: Von Massenmedien zu sozialen Medien (1918 bis heute), Wiesbaden 2019, pp. 99-123; Marion Krammer, Raging Standstill or Zero Hour? Austrian Press Photographers 1945-1955, Vienna 2022. See also the “Database of Austrian Press Photographers 1945-1955” compiled by Margarethe Szeless and Marion Krammer.

[10] In the estate of Friedrich Klinsky, see the instructions with detailed information from the publisher Fritz Molden to the photo reporters of the photo pool. See Barbara Pflaum: Wolfgang Kos (ed.), Photo: Barbara Pflaum. Bildchronistin der Zweiten Republik, Vienna 2006.

[11] See the reference to the exhibition in: Kos (ed.), Photo: Barbara Pflaum, p. 56.

[12] See the letters in the estate of Friedrich Klinsky.

[13] Günther Allinger, in: Kurier, 1964.

[14] See Anecdotes from the Kurier, Georg Markus, in: Kurier 16.10.2019.

[15] See, inter alia, Express, evening edition, 14.09.1966.

[16] Such an often used formulation from his mouth.

[17] Photo agency APA-PictureDesk, https://www.picturedesk.com/bild-disp/apa/de/home.html [22.02.2022]. In 2022 there are 71 entries under the name Fritz (Friedrich) Klinsky.