Gendered Bodies on Soviet Posters, 1917-1924

The Visual Representation of Backwardness

Women had to be drawn into the revolutionary struggle, Nadezhda Krupskaya insisted in 1913: “The woman question for male and female workers is a question how to draw the backward masses of women workers into organization, how best to explain to them their interests, how best to make them into comrades in the general struggle.”[1] Lenin also condemned women’s backwardness as interfering with the revolutionary struggle: “The domestic life of the woman is a daily sacrifice of self to a thousand insignificant trifles. [….] Her backwardness and her lack of understanding for her husband’s revolutionary ideals act as a drag on his fighting spirit, on his determination to fight.”[2]

In this essay, I explore the visual representation of that backwardness. For revolutionaries of all stripes, a core value in the revolution was overcoming Russia’s backwardness. In Russian it literally meant “lagging behind” [otstalost], but it had a wide compass to include illiteracy, superstition, drunkenness, syphilis, lack of culture, and lack of political engagement.[3] I ask how early Soviet artists conveyed this backwardness – especially as synonymous not only with ignorance, but also with “darkness” and a lack of revolutionary consciousness. How did they compose posters for the masses in those early years of Soviet power, especially during the extensive civil and national wars of 1917-1921? How and why was gender such an important part of that visual imagery?

These questions relate to the larger question of visuality more generally, especially how images can serve as tools of specific ideologies. How might images such as these complicate or even contradict a prevailing or desired gender ideology? How might such images reveal ambiguities and anxieties? What tropes and messages might these images convey that were not necessarily intended by the original image-makers?

The topic of Soviet posters – and even the topic of gender in Soviet posters – is not a new one. Victoria Bonnell, Stephen White, and many others provide excellent analyses of what Bonnell calls “the iconography of power” conveyed in such mass-produced images. Their premier work has shown that blacksmiths (typically male) in particular epitomized advanced workers, while a woman’s economic status was usually signaled by the position of her kerchief (tied behind her head for a woman worker or under her chin for a peasant woman).[4] However, there has not been enough analysis of gender-specific issues related to backwardness and forwardness during the early Soviet period.[5]

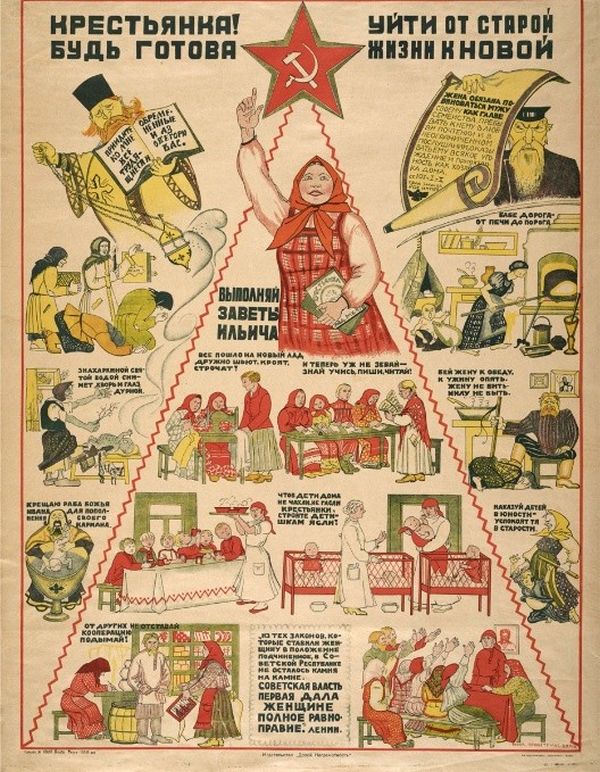

In this visual essay I would like to address two main points. First, I argue that early Soviet artists chose to represent backwardness in literal, spatial terms. Subjects (mostly men) demonstrating revolutionary consciousness tended to look and move forward or out toward the viewer, while those who were less advanced (mostly women) looked backward over their shoulders, toward the rear. Secondly, early Soviet poster artists tended to portray women workers and peasants in domestic settings that showed the old, prerevolutionary lifestyle that had to be overcome, with illustrations of poor practices including ignorant childcare, failed sanitation and hygiene, and illiteracy. As I have shown elsewhere, men were often portrayed as holy warriors, even icon-like, and vanquishing external enemies.[6] Women, as I show here, were depicted as benighted and in need of tutelage from the Communist Party, which would point them to the perfect future. These portrayals tended to perpetuate gender binaries despite early Soviet claims to women’s equality and even sameness. And they showed women as irrevocably associated with the domestic. Men, by contrast, were rarely shown in these early years as immobilized and stuck in the past. Although theoretically women could overcome the backwardness of the domestic sphere, and some posters even showed the new practices that would help them, the most vivid images depict them as old and crone-like with very disturbing features.

Of course, it is true that visual propaganda from this early, embattled period tended to be schematic by its very nature. It was created during an era of intense fighting, and the imagery had to be quickly grasped by citizens on the go. Men were more likely than women to be serving in the Red or White cavalry, riding horseback as well as holding and using arms. Women did have a greater role in the domestic sphere in popular imagination. Yet the contrast with Bolshevik propaganda in written texts is stark. While official Bolshevik PR emphasized women’s equality and their new roles in industrial production, these visual works tended to place women in classic spheres of backwardness (especially poor childrearing and medical care). Although both men and women appeared in association with illiteracy and sometimes drunkenness, nonetheless, on the whole, the posters tended to intensify gender differences in representations rather than diminishing them by showing men as active, forward-moving and women as stuck in the home and backward-looking.

This essay will examine four groups of images, all meant to be illustrative rather than exhaustive: 1) male warriors in dynamic positions; 2) women as static Marianne figures (following Eugene Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People”); 3) women following behind men and barefoot; 4) women subverting the cause, plus female “healers” propounding dangerous practices and needing basic literacy training.

Forward Charging Men

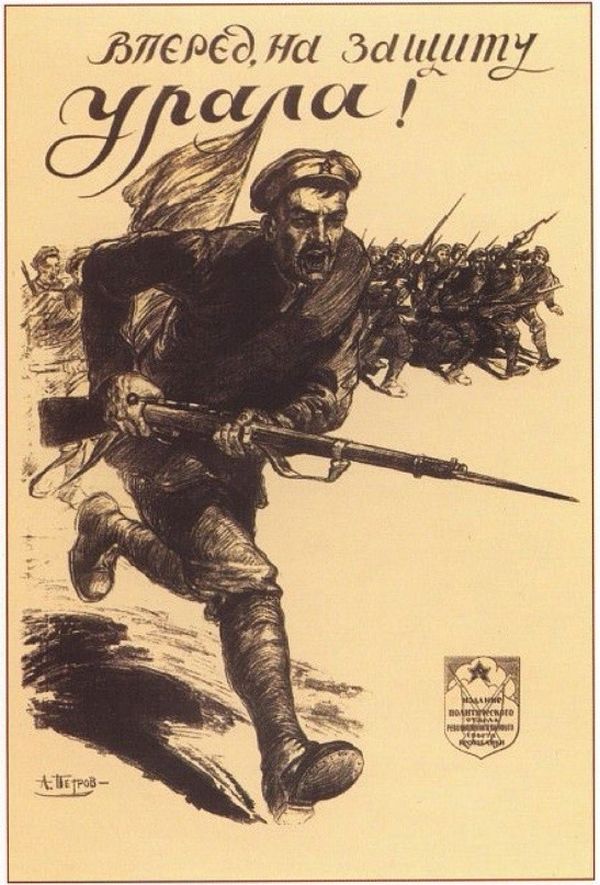

An early example of men’s dynamic movement can be seen in the image “Forward – To the Defense of the Urals!” (1919) by Aleksandr Apsit (pseud. A. Petrov). Here the lead soldier races into battle with his rifle extended and his mouth open to form a cry: “Forward! To the Defense of the Urals!” Behind him, the mass of men charge with outstretched arms and rifles. With eyes trained on the horizon and wide strides propelling them into battle, they clearly focus on their forward motion. While nothing is known about why Apsit chose this image, it seems likely that he was responding to the Bolsheviks’ 1918 spring campaign to dislodge White (anti-Bolshevik) forces in the Ural Mountains. Trotsky himself, in a speech at the time, exhorted his followers saying that while the revolution and war had reached a critical moment, “only one of these forces [fighting now] is progressive, leading mankind forward, and that is the force of the working class.”[7]

Fig. 1. Aleksandr Apsit (pseud. A. Petrov): “Forward. To the Defense of the Urals!” [Vpered,

Na Zashchitu Urala], Moscow 1919. Source: Russian Poster, [08.10.2025]

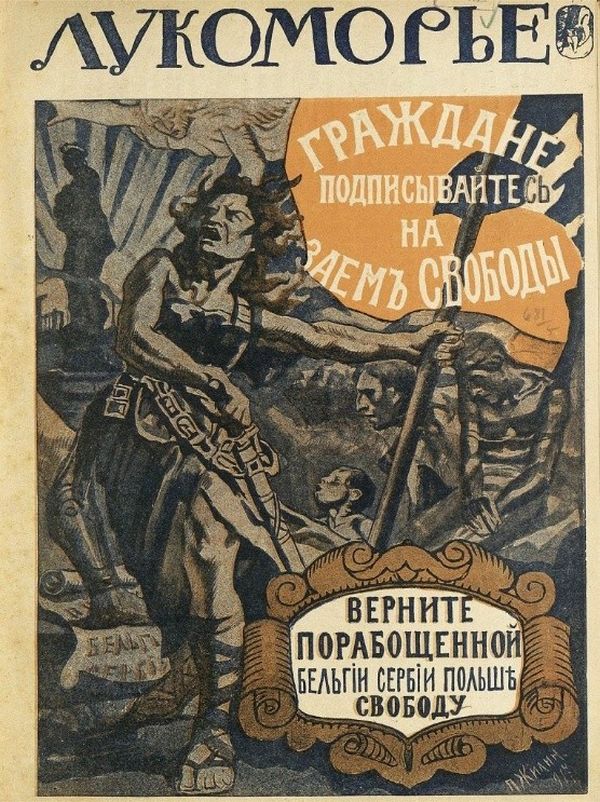

Female figures in the earliest years tended to be abstract, representing Liberty, Equality or Justice. In fall 1918, the state authorities produced a poster by Panteleimon Zhilin’s “Long Live the Great Anniversary of the Proletarian Revolution! Long Live the Commune!”[8] The central figure appears to be an allusion to Revolution itself, either as Marianne (as in Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People) or La Marseillaise of François Rude (both from the 1830s). With Medusa-like hair, her face is decidedly androgynous, even masculine. Clad in Roman sandals with a sword at her belt, she seems designed to give both a military and a masculine look as well as a classical one. In her left (muscular) arm, she grasps a red banner with the words “October 25, 1917 – November 7, 1918.” (At this time the Soviet government had changed to the Western calendar, so the authorities were doubtless signaling that henceforth the “October Revolution” would be celebrated on November 7.) The leading woman overshadows three wraith-like figures, perhaps two men and a boy, all seriously emaciated. In the background, a factory or a city streams blue rays of light toward the heavens. While she does not appear to be particularly “backward,” her androgyny suggests the difficulties of drawing a positive female figure. If she was to be a “comrade” and call others out to join the revolution, she could not be a “baba,” the backward woman. But it is difficult to see her as any kind of role model for women workers and peasants.[9]

Fig. 2. Panteleimon Zhilin: “Long Live the Great Anniversary of the Proletarian

Revolution! Long Live the Commune!” Cover “Lukomor’e”, No. 19-20, June 17, 1917.

Source: Laboratoriia fantastiki, https://www.fantlab.org/edition430514 [08.10.2025]

Fig. 3. Plotnik Grav: “Woman Worker of Free Russia! Hold your Communist Banner

more Firmly. Behind you the Women of the whole World Go to Battle against Capital”

[Rabotnitsa Svobodnoi Rossii! Krepche derzhi znamia kommunizma. Za toboi idut

zhenshchiny vsego mira na bor’bu s kapitalom], 1921. Source: Pikabu, [08.10.2025]

Many revolutionary images conveyed just one or two men, usually a worker and a peasant, to portray the idea of smychka, i.e., joint revolutionary union of those two classes. While some did include female figures, they were often portrayed as third, behind the other two. Or they were helpers in some way, who facilitated the work of the men.

Fig. 4. Aleksandr Nikolaevič Samokhvalov: “Long live the Komsomol! Toward the 7th

anniversary of the October Revolution” [Da zdravstvuet Komsomol! K sed’moi

godovshchine Oktiabr’skoi revoliutsii], Leningrad 1924. Source: Russian Poster [08.10.2025]

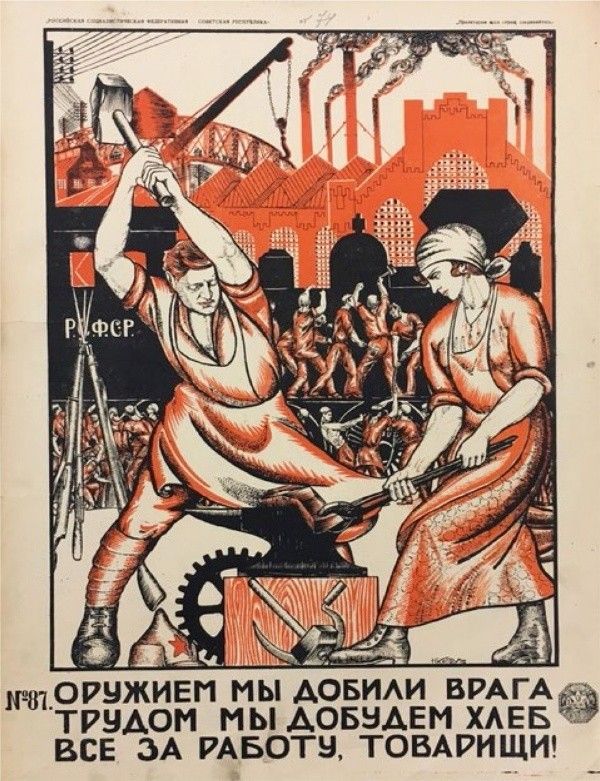

Fig. 5. Nikolai Kogout: “With our Weapons we Defeated the Enemy. With our

Labour we Shall Have Bread. Everyone to Work, Comrades!” [Oruzhiem my dobili

vraga. Trudom my dobudem khleb. Vse za rabotu, tovarishchi!], Moscow 1920.

Source: Russian Poster [08.10.2025]

Fig. 6. Unknown artist: “What Has the October Revolution Given the Woman

Worker and Peasant” [Chto dala Oktiabr’skaia revoliutsiia rabotnitse i ‘krest’ianke],

Moscow 1920. Source: Russian Poster [08.10.2025]

At the same time, she also looks over her shoulder, away from the future idyllic scene. The posters’ title emphasizes what the October Revolution has given women, not what women have taken or won through struggle. In other words, women are the recipients, more than the actors. The buildings in the background are topped by the maternity hospital, linking women firmly to the domain of motherhood – Soviet propaganda rarely discussed parenting by fathers or other individuals. And she is standing still. In this, she resembles more the messenger than the activist, more Angel Gabriel in the Annunciation than Delacroix’s Liberty.

Dangerous and Backward Women

Perhaps the most iconic image of women’s backwardness and one of the earliest was Mikhail Cheremnykh’s famous “Story of the Bubliki (Bagels) and the Baba who Did not Acknowledge the Republic” (1920). Here a quintessentially backward woman (the baba) sells bubliki, refusing to give any to the Red Army soldier, as a result of which she ends up being swallowed whole by the greedy Polish pan (rich man). Vladimir Mayakovsky’s poem, which was reproduced on this poster, ends with the moral of the story: “Feed the Red [Bolshevik] warriors and bring your grain without howling [i.e., without resistance].”

Fig. 7. Mikhail Cheremnykh: “Story of the Bubliki (Bagels) and the Baba who Did not Acknowledge the Republic” [Istoriia pro bubliki i pro babu, na priznaiushchuiu Respubliki], Petrograd 1920. Source: Russian Poster [08.10.2025]

Fig. 8. Moskovskii proletkul’t. V.Kh.M.A: “Peasant Woman! Be Prepared to Go from the Old Life to the

New” [Krest’ianka! Bud’ gotova uiti ot staroi zhizni k novoi], 1920. Source: Duke University [08.10.2025]

Fig. 9. Unknown artist: “Protect your Children from Infections. Don’t Kiss Children on the Lips. Give

Children more Fresh Air and Sunshine.” [Beregite detei ot zarazy. Ne tseluete deti v guby. Daite detiam

bol’she vozdukha i solntsa], Source: Stena, [08.10.2025]

In “Protect Your Children from Infections” (anonymous, 1920s), the viewer is instructed “Don’t Kiss Children on the Lips. Give Children more Fresh Air and Sunshine.” Here a crone stands to the left as the mother pushes her away from the child. The mother with her kerchief tied behind her head (symbolizing that she was closer to being a woman worker than a peasant) sits peacefully outside a wooden house with a healthy toddler on her lap. The sunshine, beautiful house, dog, and leaves on the tree suggest a wholesome environment. The old woman, by contrast, encroaches with extended arms to take the child. Wearing a scarf tied below her chin (as peasant women did) and a long apron with folk designs, the older woman has skin darkened from the sun and enlarged lips. The age and skin tone of the older woman seem clearly designed to convey the danger she represented to the blond, white-skinned child.

Fig. 10. Okhmatmlad: “Give Birth in the Hospital. [Otherwise] the Woman Healer [Babka] Will Cripple your Health” [Radi v

bol’nitse. Babka kalechit tvoe zdorov’e], 1920s. Source: pikabu [08.10.2025]

As in Western Europe and North America in the 19th century, women healers were now being marginalized and excluded in favor of medical doctors.[13] To encourage this change through visual media, the older women had to be stigmatized with long noses and grim expressions. In the “new” sanitized world, they had to literally be erased from the image of the hospital and the healthy new mother.

Fig. 11. Book cover of the courtroom drama “Kurynikha. Trial of a Woman Healer

/ Kurynicha. Sud nad znacharkoj”, 1925, published by the Leningrad branch of Proletkul’t

One of the most striking images of a so-called wise woman [znakharka or babka] made to look evil is not a poster but rather the cover of a play called “Kurynikha: Trial of a Woman Healer” (1925). The eponymous Kurynikha, whose name means “chicken,” looks out at the viewer with her long fingers poised over a soup bowl that resembles a cauldron. With her green coloring, wide eyes, long nose, and toothless, gaping mouth, she can only be seen as a witch. Her nickname – the chicken lady – moreover, reminds the viewer of the famous Slavic witch Baba Yaga, whose house stands on chicken legs and who herself is sometimes known as the “bony-legged one.” As in the previous image, the clear message here is that the woman healer, who is untrained and superstitious, will cause harm with her ignorant practices and beliefs.[14]

Fig. 12. “Are You Helping to Liquidate Illiteracy? Everyone Join the ‘Down with

Illiteracy’ Society.” Leningrad 1925. Source: Wikimedia Commons [08.10.2025]

In “Are You Helping to Liquidate Illiteracy?”, the central woman looks squarely at the viewer. She is both dynamic and demonstrative. Yet, viewers would have automatically compared her, perhaps seeing her as secondary and derivative to Moor’s “Did You Volunteer?” It is also possible that the motif would have evoked the WWI propaganda of the “Women’s Battalion of Death,” that was explicitly designed to shame male laggards who had failed to volunteer for the front. For the organizers of Likbez, the poster “Are You Helping to Liquidate Illiteracy?” used this kind of military imagery to indicate the critical importance of this campaign. Both women and men would have been shamed into joining Likbez with an eye to eliminating their unacceptable illiteracy.

Fig. 13. Elizaveta Kruglikova: “Learn to Read and Write. Oh, Mama. If only You Were Literate – You

Would be able to Help Me!” [Ekh, Mamania! Byla by ty gramotnoi, pomogla by mne!], Petrograd 1923.

Source: Russian Poster [08.10.2025]

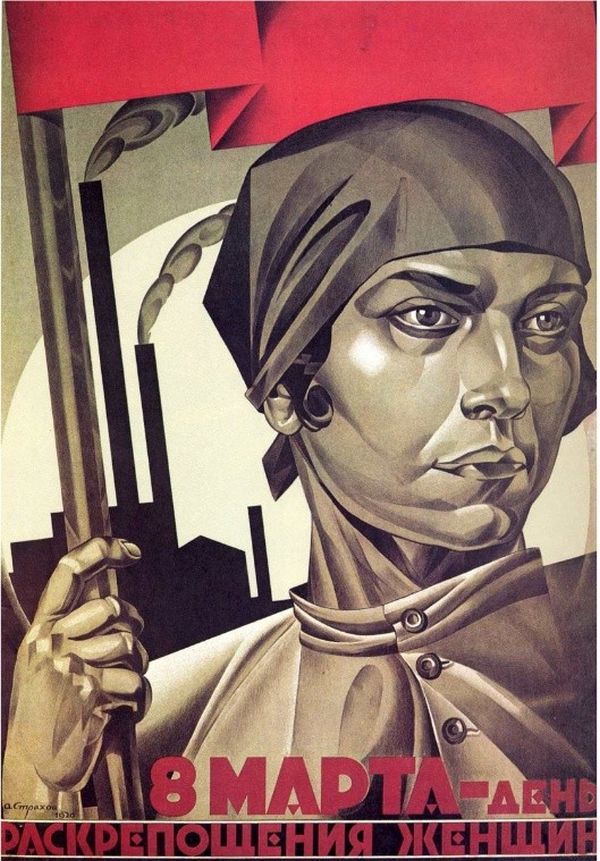

Fig. 14. Adol’f Iosifovič Strachov-Braslavskij: “March 8 – Day of Women’s

Emancipation” [8 marta – den’ raskreposhchenia zhenshchin] 1926. Source:

Russian Poster [08.10.2025]

Conclusion

From this brief sketch of these four categories – forward men, ugly “Mariannes,” lagging women, and backward, passive women – we see that there were few positive images of women. Backwardness shows up in women’s positions behind men, their lack of movement and dynamism, the danger they might bring to the revolution through their ignorance. Even when women are shown with the most advanced images of the day – smokestacks and the gifts of the revolution – they are shown in heraldic positions rather than fighting ones.

[1] N.K. Krupskaya, Editorial for the first issue of Rabotnitsa (Feb. 13, 1914), in: Istoricheskii arkhiv 4 (1955), p. 38.

[2] Clara Zetkin, Lenin on the Women’s Question, Marxists Internet Archive, https://www.marxists.org/archive/zetkin/1925/lenin/zetkin2.htm [08.10.2025].

[3] This question of backwardness is a key focus of my first two monographs: Elizabeth A. Wood, The Baba and the Comrade: Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia, Bloomington, IN, 1997; idem, Performing Justice: Agitation Trials in Early Soviet Russia, Ithaca, NY 2005.

[4] Victoria E. Bonnell, Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin, Berkeley 1997; id., The Representation of Women in early Soviet Political Art in: Russian Review 50.3 (1991), pp. 267-288; id., The Peasant Woman in Stalinist Political Art of the 1930s, in: The American Historical Review 98 (1993), pp. 55-82, online https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article/98/1/55/64207 [08.10.2025]; id., The Iconography of the Worker in Soviet Political Art, in: Lewis H. Siegelbaum/Ronald Grigor Suny (eds.), Making Workers Soviet: Power, Class, and Identity, Ithaca 1994, pp. 341-375; Stephen White, The Bolshevik Poster, New Haven, 1989; Elizabeth Waters, Childcare Posters and the Modernisation of Motherhood, in: Sbornik: Study Group on the Russian Revolution 13 (1987); id., The Female Form in Soviet Political Iconography, 1917-1932, in: by Barbara Evans Clements/Barbara Alpern Engel/Christine D. Worobec (eds.), Russia’s Women: Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation, Berkeley 1991, pp. 225-242; Susan Reid, All Stalin’s Women: Gender and Power in the Soviet Art of the 1930s, in: Slavic Review 57 (1998), pp. 133-173; Frances L. Bernstein, Envisioning Health in Revolutionary Russia: The Politics of Gender in Sexual-Enlightenment Posters of the 1920s, in: Russian Review 57.2 (1998), pp. 191-217; Anna N. Eremeeva, Woman and Violence in Artistic Discourse of the Russian Revolution and Civil War (1917-1922), in: Gender & History 16.3 (2004), pp. 726-743, online https://sites.bu.edu/revolutionaryrussia/files/2013/09/Women-and-Violence-Civil-War.pdf [08.10.2025]; Tricia Starks, The Body Soviet: Propaganda, Hygiene, and the Revolutionary State, Madison, WI, 2009.

[5] It should also be remembered that “Forwards” [Vpered] was the name of a large number of German, Yiddish, and Russian socialist periodicals. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, in his “The General Idea of the Revolution in the 19th Century” (1851), called on socialists to move forward: “What, then, are we waiting for? Forward! and at full speed, against land rent.” The Anarchist Library, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/pierre-joseph-proudhon-the-general-idea-of-the-revolution-in-the-19th-century [08.10.2025].“Vorwärts!” [Forward] was used as the title for a number of European and American Jewish publications: the first in Paris in 1844; the second, the leading newspaper of the German Social Democratic Party from 1876 until the present; and the third, Forṿerṭs, a Yiddish-language daily newspaper in the US from 1897 to today. In Russian Vpered [Forward] was the title of a journal and a newspaper published abroad from 1873-1877, both of them extremely influential. Lenin and the Bolshevik leadership frequently exhorted their followers to go forward.

[6] Elizabeth A. Wood, Gender Images in the Russian Revolution: Backward Women and Forward Men in Iconic Perspective, 1919-1923, in: Carol Leonard/Daniel Orlovsky/Jurej Petrov (eds.), The Russian Revolution of 1917-Memory and Legacy, Routledge 2024, pp. 176-190.

[7] Leon Trotsky, “The Eastern Front”. Speech at the Joint Session of the Samara Province Executive Committee, Committee of the Russian Communist Party and Representatives of the Trade Unions,” April 6, 1919, Marxists Internet Archive, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1919/military/ch112.htm [08.10.2025].

[8] The image seems originally have been used on the cover of the popular journal Lukomor’e, No. 19-20, June 17, 1917, as part of an appeal by the Provisional Government for Russians to buy liberty bonds. Laboratoriia fantastiki, https://www.fantlab.org/edition430514 [08.10.2025].

[9] Yulia Gradskova makes a passing but very important comment about the tension between androgyny and maternalism in the Revolution in her work: Soviet People with Female Bodies: Performing Beauty and Maternity in Soviet Russia in the mid 1930-1960s. PhD diss., Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, 2007, pp. 14-15. See also Natalia Budanova, Utopian Sex: the Metamorphosis of Androgynous Imagery in Russian Art of the Pre-and Post-Revolutionary Period, in: Christina Lodder/Maria Kokkori/Maria Mileeva (eds.), Utopian Reality: Reconstructing Culture in Revolutionary Russia and Beyond, Leiden 2013, pp. 25-41.

[10] For another picture of a sickle-bearing peasant woman walking a step behind two men, see the poster, “May 1st, 1920. Through the Shards of Capitalism to the Universal Brotherhood of Laborers [1oe maia, 1920 goda, Cherez oblomki kapitalizma k vsermirnomu bratstvu trudiashchikhsia], Moscow 1920. Russian Poster, https://russianposter.ru/poster.php?rid=10010146100000 [08.10.2025].

[11] Elizabeth Waters, The Modernisation of Russian Motherhood, 1917-1937, in: Soviet Studies 44 (1992), pp. 123-135.

[12] For a full series of photos of Okhmatmlad posters, see pikabu: Пикабу, “Серия плакатов Охрана Материнства и Младенчества 1925 года,” https://pikabu.ru/story/seriya_plakatov_okhrana_materinstva_i_mladenchestva_1925_goda_12324924 [08.10.2025].

[13] Waters, Modernisation; Yulia Gradskova, Helping the Mother to be “Soviet”: The Medicalisation of Maternity and Nursery Development in Russia in the 1920 and 1930s, in: Gisela Hauss/Dagmar Schulte (eds.), Amid Social Contradictions: Towards a History of Social Work in Europe, Opladen 2009, pp. 225-236. For Europe and North America, the classic work is Barbara Ehrenreich/Deirdre English, For her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women, Garden City 1978.

[14] Anonymous, Kurynikha. Sud nad zhakharkoi, Leningrad 1925; for further discussion, see: Elizabeth A. Wood, Performing Justice: Agitation Trials in Early Soviet Russia, Ithaca 2005, p. 143. The image is also reproduced in Gianna Frölicher, Theater mit Unsichtbaren: Mikroben vor Gericht, https://geschichtedergegenwart.ch/theater-mit-unsichtbaren-mikroben-vor-gericht/ [08.10.2025]. A famous pre-Soviet Russian proverb also comments: “A chicken is not a bird, and a woman is not a person.” For more on Baba Yaga, see Joanna Hubbs, Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture, Bloomington 1988, pp. 36-51.

[15] Cited in: James Taylor, Your Country Needs You: The Secret History of the Propaganda Poster, Manchester 2013, p. 7.

[16] See the biography of Elizaveta Kruglikova on Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizaveta_Kruglikova, and a collection of her graphics at the Internet Archive, https://web.archive.org/web/20090203152338/http://graphic.org.ru/kruglikova.html [both 08.10.2025].

[17] While the broom was not used by the most famous witch Baba Yaga to ride on, she was frequently depicted using a broom to erase her tracks as she traveled in a mortar. Baba Yaga, Encyclopedia of Brokgaus and Efron, 1906, see Wikisource https://ru.wikisource.org/wiki/%D0%AD%D0%A1%D0%91%D0%95/%D0%91%D0%B0%D0%B1%D0%B0-%D1%8F%D0%B3%D0%B0 [08.10.2025].

[18] In Russian, “bab’ia doroga – ot pechi do poroga.” The woman’s part of a small one-room peasant hut was called the “babii kut” or “babii ugol.”

This article is part of the theme dossier “Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive,” edited by Christina Benninhaus and Mary Jo Maynes.

Theme Dossier: Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive

Zitation

Elizabeth A. Wood, Gendered Bodies on Soviet Posters, 1917-1924. The Visual Representation of Backwardness, in: Visual History, 20.10.2025, https://visual-history.de/2025/10/20/wood-gendered-bodies-on-soviet-posters-1917-1924/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2953

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Eine Nutzung ist für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in unveränderter Form unter Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de