Mediated Memories: Holocaust Narratives and Iconographies in Lithuania After 1990

A family in the streets of the Kovno ghetto. On the pavement, at the bottom right, a clandestine ghetto photographer, George Kadish, captures his own image as well, Kovno, Lithuania, 1941, photographed by George Kadish. Source: Courtesy of U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives ©

This research examines mediated memories of the Holocaust in Lithuania from 1990 until today. After the restoration of Lithuanian independence in 1990, different means of media created an alternative arena for Holocaust memorialization, where conflicting narratives and iconographies confronted each other. The analysis of this dissertation project focuses on Holocaust narratives presented in Lithuanian press and on photographic imagery as well as filmic visualizations of the mass murder of Lithuanian Jews. This work offers a multi-perspective insight into how memories of the Holocaust are narrated, visualized and gendered in the context of media. The purpose of this dissertation project is to contribute to Lithuanian memory research in the field of Holocaust studies.

Films, photographs, and press, that comprise the main corpus of this work, all of them are objects, which could be seen as “agents in the constructions of memory.”[1] They not only retell the past, but also create Holocaust narratives and iconographies as well as mediate relationships between distinct individuals and groups.[2] Israeli media scholar Amit Pinchevski designated mediated memories as “the various forms by which memory is formed and shared by means of media technologies.”[3] In this research, I argue that these mediated memories cross national borders and can also be found within different Lithuanian Jewish communities living abroad. Therefore, the Holocaust remembrance in Lithuania cannot be investigated without the inclusion of narratives and iconographies transmitted by the transnational Lithuanian Jewish diaspora.

At the outset of this study the development of Holocaust narratives in Lithuanian press is explored and a periodization of Holocaust memorialization in Lithuania is offered. Three main periods, revealing the existence of distinct Holocaust narratives in different historical moments, are distinguished. In the first years of independence from 1990 to 1995, Jewish voices and memories of the Holocaust were forgotten. There existed a certain media consensus to speak only about the heroism of anti-Soviet partisans and Lithuanian victimhood during the Soviet occupation. In the years of integration into Western organizations between 1995 and 2004, Holocaust has emerged as a historical, political and media topic. The accession to the EU and NATO required Lithuanian foreign policy to consider the issue of the Holocaust. The year of 2004, when Lithuania entered the EU and NATO, was identified as another moment of change in Holocaust memorialization. Lithuanian politicians started to use the Holocaust as a template for the acknowledgment of the communist crimes of the Soviet regime. Consequently, the Holocaust emerged as a competitive memory of the Second World War.

The subsequent analysis focuses on iconographies of the Holocaust in Lithuania in film and photography. The filmic representations of Lithuanian Jews returning to their homeland, as this is the most recurring narrative in the documentary films related to the Holocaust in Lithuania, are investigated. The work claims that documentary films, in contrast to the Lithuanian press, gave Lithuanian Jews a possibility to represent their own memories. The medium of documentary film for many Lithuanian Jews served as a possibility to return to a lost homeland, to visit the places of mass executions and to retell their traumatic pasts. At the same time, for other Lithuanian Jews, the process of documentary filmmaking itself converted into a site of memory and acted as a safe substitution for their impossible physical return to a homeland, which has completely disappeared after the war.

The visual perspective on the Holocaust is enriched by the analysis of photographs taken during the mass murder of Jews in Lithuania. This introspection of images has not limited itself to the visual perception of the perpetrators and their imagery of the war, but has also concentrated on photographs clandestinely captured by the Lithuanian Jews. Holocaust photographs can be divided into several categories. Literary scholar Marianne Hirsch observes that the identity of the photographer, namely, perpetrator, victim, bystander, or liberator is “a determining element in the photograph’s production, and that, as a result, it engenders distinctive ways of seeing and, indeed, a distinctive textuality.”[4]

This study explores photographs which were recorded by perpetrators. These images were taken as brutal acts of humiliation of the Jewish victims. They embody an inquisitorial gaze of a Nazi camera. Holocaust scholar Brad Prager, who analyzes perpetrator photographs, remarks that the camera was “a metonymic extension of Nazi weaponry.”[5] In this work, the images made during the mass atrocities by the Nazi photographers in the Lietūkis garage in Kovno on June in 1941, are examined more thoroughly. The analysis of these pictures reveals not only the framework of these photographs, but also explore the voyeuristic gaze of the perpetrators, who captured these images of death. It is discussed that victims can be shot not only by weapons, but also through the camera lenses.

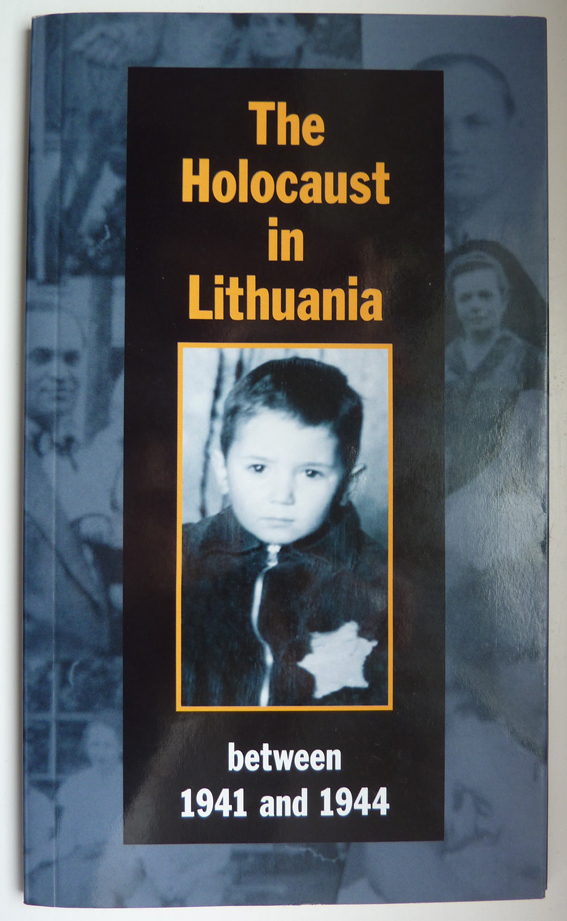

Two brothers from the Kovno ghetto before their deportation to the Majdanek camp, Kovno, Lithuania, February 1944, photographed by George Kadish. Source: Courtesy of U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives ©

An important aspect of this research is pictures taken by Jewish victims. French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman, who scrutinized the images of Sonderkommando at Auschwitz, described these photographs as the “images in spite of all,” since they reflect the resistance of the Jewish victims.[6] In Lithuania clandestine pictures were taken in the Kovno ghetto by George Kadish, an amateur photographer. His photographs depicted the ghetto streets and portraits of the Lithuanian Jews. The work suggests that Kadish, while recording the life in the ghetto with his camera, resisted the Nazi regime that wanted to completely erase not only the Jews but also any traces of their existence. In contrast to the Nazi imagery, he depicted the Jews in the Kovno ghetto as human beings and not as a pile of dead corpses. His photographic records sought to display that the inhabitants of the ghetto, in spite of the harsh conditions and humiliations, were capable of surviving in a human manner. Therefore, it is not surprising that these portrayals until today are worldwide mediated, and act as important sources of visual material in the memoirs of the Lithuanian Jewish survivors. In some cases, they even have triggered memories and evoked remembering and writing about the Holocaust in Lithuania.

A fragment from George Kadish’s photograph of two brothers in the Kovno ghetto on the cover of the book written by Arūnas Bubnys “The Holocaust in Lithuania between 1941”, published in 2008 by the Genocide and Resistance Centre of Lithuania 2005 © courtesy of

This research also investigates how the memory of the Holocaust in Lithuania has been gendered through different media. The emergence of female partisan narratives, which have been overshadowed by the male narrative of resistance during the Second World War, is debated. The representation of a Jewish woman as an object of sexuality in the single Lithuanian feature film Ghetto and the use and abuse of child narratives are examined. In this article, I show a photograph from the book The Holocaust in Lithuania between 1941 and 1944, published in 2008 by the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre in Lithuania. The image of a boy, used for the cover of this publication, is a fragment from Kadish’s image of two brothers Avram and Emanuel Rosenthal, five and two years old, captured before they were deported from the Kovno ghetto to Majdanek extermination camp. The photograph of these two brothers on the book’s cover is decontextualized and might be perceived as a visual portrayal of any child. The child’s image becomes central and transcends the pictures of other Lithuanian Jews. Such medialization turns the child figure into a symbol of all Jewish victims and the child victim becomes a symbolic figure of reconciliation and forgiveness in the context of the Holocaust remembrance in Lithuania.

[1] James Edward Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning, New Haven 1993, p. xi.

[2] José van Dijck, Mediated Memories in the Digital Age, Stanford 2007, p. 1.

[3] Amit Pinchevski, “Archive, Media, Trauma,” in: Motti Neiger/Oren Meyers/Eyal Zandberg (eds.), On Media Memory. Collective Memory in a New Media Age, London 2011, p. 253.

[4] Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust, New York 2012, p. 133.

[5] Brad Prager, “On the Liberation of Perpetrator Photographs in Holocaust Narratives,” in: David Bathrick/Brad Prager/Michael D. Richardson (eds.), Visualizing the Holocaust: Documents, Aesthetics, Memory, New York 2008, p. 22.

[6] Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All. Four Photographs from Auschwitz, Chicago 2008 [2003].