Customs and Declarations: Research Strategies for Uncovering the Hidden History of a Black Woman Photographer

“Where are the Black women photographers?”

This question, posed by photographer Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, resonates on multiple levels for scholars of visual studies. While it might prompt readers to list contemporary Black women photographers, few could name practitioners from the nineteenth or early twentieth century when pressed.[1] For some, the question itself poses the realities of intersectionality, the way that gender and race have elided history, experience and opportunity. For others, the query might call to mind the examination of art history’s history by Linda Nochlin in 1971, when she inquired, “Why have there been no great women artists?”.[2] Both inquiries begin with a presumption and seek to address the dearth of historical information on women and both recognize systemic institutional obstacles to women’s creation, participation and the documentation of their efforts within history.

There is, however, a substantive difference in how each inquiry is framed. Nochlin approaches her query from the presumption that there were no great women artists, and then examines the social, cultural and political circumstances that prevented women, with some notable exceptions, from becoming “great.” Her argument focuses on the expectations of art as well as the shifting determinants of what constitutes greatness. Moutoussamy-Ashe frames her question not as a why, nor does she impose a hierarchical qualification. Instead, she presumes that there were Black women photographers, but their location within history is unknown. It is a question of presence, not absence. Yet, for those of us engaged in photographic histories concurrent with the nineteenth century development of the technology of photography, there is a notable lacuna in our awareness of the contributions made by Black women.

The Question of Presence

Guided by her prompt, Moutoussamy-Ashe set out to find the work and the histories of Black women photographers, resulting in the groundbreaking book, “Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers”, a survey that covers 146 years of image making by African American women working in the United States.[3] Published in 1986, then revised and expanded in 1993, this text not only impacted the history of photography, but also how archival research can be approached. Without discrete collections of their own, any awareness of the contributions of Black women photographers is challenging to recover, and reveals the fraught history of archival collecting – posing additional questions as to which archives are acquired and preserved, as well as by whom and to what degree they become accessible. In effect, Moutoussamy-Ashe’s book is not only about the work of Black women photographers but also about the work of getting access to and trying to understand their histories. Because of her efforts and those of scholars who follow such as Valencia Coar and Deborah Willis, among others, it is possible to critically consider the work that these images accomplished, especially in regard to challenging expectations of race, gender and class.[4]

For this article, I would like to present the process of my becoming aware of the work of Charlotte Paige Carroll, an African American woman photographer active in Chicago during the 1920s-1940s. This period, notably marked by the Harlem Renaissance – a flourishing of African American art and culture – fostered a modern Black subjectivity known as the “New Negro”.[5] More of an international movement of Black consciousness than a phenomenon that was limited to a particular geography, the Harlem Renaissance promoted a period of cultural growth, economic investment and political agency. It is within this context that Carroll, with her partner J.C. Schlink, owned and operated Electric Studio, generating countless images of individuals, organizations and events. Electric Studio’s photographs were published in nationally circulating newspapers and magazines, and aspects of Carroll’s life were chronicled in the Black media of the day, yet despite the significant contributions of Carroll or Electric Studio their extensive efforts do not appear in the chronicle of photography’s history. For numerous reasons – from the historical devaluation of commercial photography to a myriad of determinations around archival preservation and the systemic racism and misogyny faced by women of color – this absence is a history in and of itself that necessitates careful consideration in both methodology and approach.

The Challenges of Archival Research

Just as a beginning point, there are a number of conventional ways of interacting with photographs that remove the creator’s history. Scholars frequently use photographs as social documents, without crediting the maker or even directly engaging the subject or the formal qualities of the image. Rather, in this context, the photograph serves as an illustration in support of the author’s narrative, engaging the subject, but rarely connected to its creator. In the process of layout and design, many scholarly publications crop out the photographer’s signature or imprint, seeking to be unburdened by its indexical specificities. Further, within the processing of archival collections, the identity of the subject of the photograph is prioritized over the photographer’s name, address and other details, resulting in the near erasure of this pertinent information in what Antoinette Burton refers to as the critical “backstage of the archives,” including catalogues, finding aids and more recently databases.[6] Such omissions impede research and prevent scholars from networking across collections held at different institutions.

The history of positioning the photograph as “art” also contributed to the hierarchical devaluing of the efforts of commercial studios, making their records seem less relevant to preserve. Since the early 1900s debates that privileged the photographer’s personal creative expression advanced, elevating some practitioners into a more rarefied realm, whereas the goal of commercial photographers remained tied to the desires and interests of their patrons. The advance of technology, especially the shift from large format to handheld cameras made the medium more accessible, decreasing the necessity of visiting the photographic studio. As Pierre Bourdieu and his collaborators have argued, amateur photographers frequently adapted the poses, staging and setting that defined the studio portrait, replacing the professionally trained photographer.[7] For some scholars, these images of the everyday – whether taken by a professional or amateur – constitute vernacular photography, one of the most important modes of representation of African American lives.

Photo historian Brian Wallis argues that vernacular photography from the 1890s through the 1930s merits careful consideration as it establishes an everyday language of visual conventions and social rituals.[8] Wallis also argues that vernacular photographs “are defined more by their destination than their origin,” with most intended for the “private album than public exhibition.”[9] Historically, this may have held true, but institutions today are actively collecting and displaying Black photography to address the racist exclusion of African American histories from their collections. In doing so, they shift the value and narrative of both amateur and professional photographs, broadening the meaning of the term “vernacular.”

Of particular note are the collections assembled by Daniel Cowin, now at New York’s International Center for Photography, and by Robert Langmuir, that were recently acquired by Emory University. Both were amassed with the intention of supporting research in African American history and contain a wide array of types of photographic media from the mid-nineteenth to twentieth centuries.[10] Not only do these collections afford the opportunity to see broadly across time and place, fostering a sense of community and shared experiences, they also provide a critical counterpoint to the hegemonic nature of the archive, allowing for the mixing of gender, race, and class that challenge previously accepted divisions and epistemologies.[11] Yet, too often these scenes of everyday Black life have become detached from their patrons and are categorized by events like weddings or professions identified by uniforms such as soldiers. In this way, “the vernacular” can become reductive, risking the repetition of diminishing the subjects, makers, and in turn, viewers.

There are strategies, however, to counter both the loss of information and the perniciousness of generalization that I apply to my initial engagement with the work of Charlotte Paige Carroll. The first is to recognize the historic role that self-representation has played in the campaign for equality and civil rights. Since the writings of Frederick Douglass and the visual activism of Sojourner Truth, as well as W.E.B. Du Bois’s “American Negro” Exhibit at the 1900 Paris Exposition, photographs of African American subjects have been charged with the work of self-realization, countering stereotypes generated to oppress and cultivate prejudice.[12] Tracing this work, connecting it to its original site, affords the opportunity to see the photograph and its contingencies. Yet, for the reasons laid out above, the arc of the photograph’s origin and subject may not initially seem retrievable. In her article, “Imperfect Archives and the Historical Imagination,” historian Leslie M. Harris reminds us of the dangers of “positing the archive as silent in terms of African American voices often extends into the idea that there is nothing to be said about African Americans.” Instead, she calls upon the skills of interpretation and imagination through which it is possible to build outward with extant fragments, adjacent experiences and recuperative acts.

Following scholar Saidiya Hartman, I employ a method of partial fashioning, what she refers to as “critical fabulation” in which the known facts of the photographers’ lives mix with concurrent experiences of others in an attempt to construct a speculative contextual skein that addresses the possibility of not only knowing more, but also the promise of knowing differently.[13] In broad strokes, following Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and Linda Nochlin, I want to interrogate “the production of our knowledge about the past,” acknowledging the “ongoing, unfinished and provisional character of this effort,” in order to make way for future possibilities of knowing the work of Black women photographers.[14]

A Tailor’s Archive: Finding Charlotte Paige Carroll

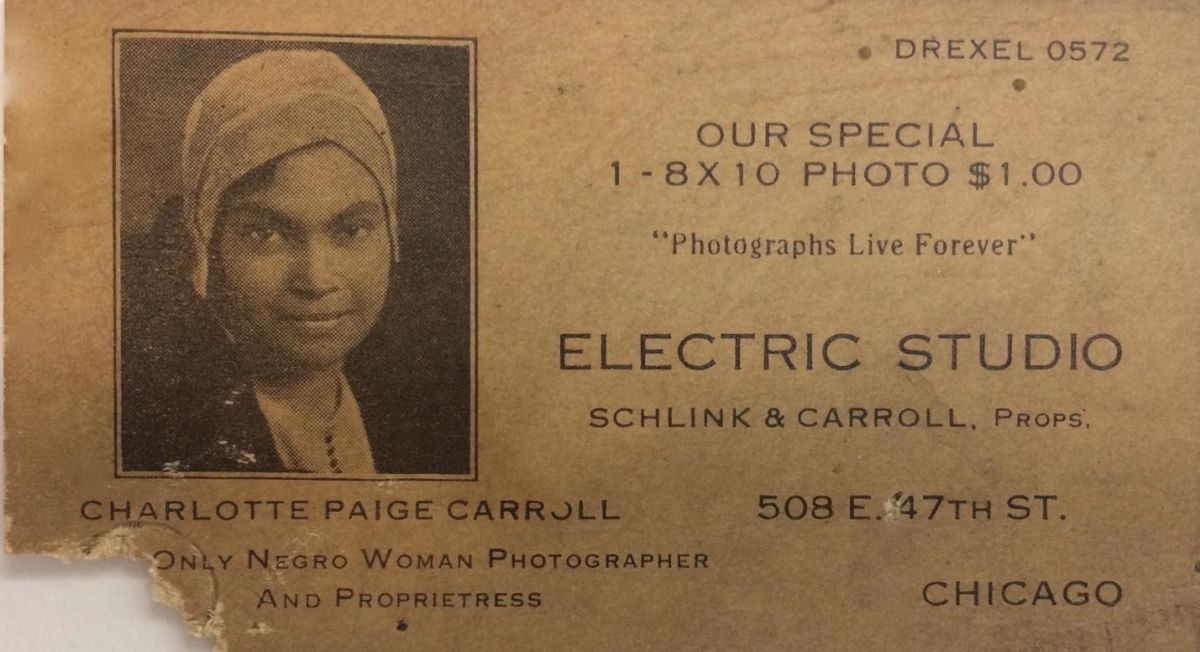

I came to know of Charlotte Paige Carroll through encountering her business card in the archival collection of Louis “Scotty” Piper at the Chicago History Museum (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Business Card of Charlotte Paige Carroll of Electric Studio, c. 1930. Source: Louis “Scotty” Piper Collection, Chicago History Museum

Piper was a tailor working in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, who was renowned for the bespoke suits he created for prominent African Americans such as athlete Jack Johnson and composer and musician Duke Ellington. During his fifty years in business, he amassed a collection of photographs of his patrons and directed customers to the local photography studios. For so many reasons this card is unique in the information that it bears. As evident from the push pin impression and the torn corner, this photographer’s card was clearly handled frequently as a point of referral. An 8 x 10 print of the photograph reproduced on the card is also included in Piper’s archives, making Carroll’s likeness part of the constellation of luminaries that constituted the tailor’s community (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Electric Studio, Portrait of Charlotte Paige Carroll. Source: Louis “Scotty”

Piper Collection, Chicago History Museum, ICHI-173664

It is unclear if this photograph was taken by Carroll herself or another employee of Electric Studio, but either way it presents a woman of self-determination.[15] With a slight smile and a direct gaze that engages the camera and subsequent viewer, Carroll presents herself as a fashionable “New Negro” woman. As an evolving and multi-valent identity, the “New Negro” emerged as a rhetoric device during Reconstruction and comes to represent a modern, urban Black subjectivity.[16] Yet, initially, for Black women, the role was infused with Victorian mores that positioned women as “helpmates” to their husbands, bound to the politics of respectability.[17] By the early twentieth century, however, a global movement of New Women unfolded in which “women transgressed the boundaries of the domestic sphere and sought to expand their rights.”[18] It is at this intersection that I can begin to trace Carroll’s negotiations of race and gender. Because of the agency apparent in her self-presentation, Carroll can be compared to the Black women that historian Deborah Willis championed for challenging “negative representations by visiting photography studios and constructing images that represented their real or desired lifestyles.”[19] In her cloche hat, high collared coat, and blouse with delicate buttons at the center, Carroll models a fashionable sensibility that Piper and other patrons must have appreciated.

Beyond its social significance, Carroll’s portrait also demonstrates her studio’s technical competence. Photographically, Carroll’s portrait is in keeping with contemporary aesthetic conventions; half-length, carefully lit from both front and back with a plain background – no painted backdrop or other details of place or time. The focus is on the subject and only the subject, reflecting a modern subjectivity. This sense of importance and confidence is echoed in the card’s text which promotes the studio’s capacities – addressing both the economy and the value of the photograph – stating that the price for one 8 x 10 photo is only one dollar and prophetically pronouncing that “Photographs Live Forever.” The card lists Electric Studio as a collaboration between Carroll and Schlink, a partner about whom at this point in the research little is known.[20]

Fashioning Identity: Agency and the Press

The most telling information on the card, however, comes from Carroll’s self-pronouncement of being “The Only Negro Woman Photographer and Proprietress.” As an act of self-determination, this straightforward declaration of gender, race and profession counters the historic lacuna with the consciousness of being “the only.” Because of the work of Moutoussamy-Ashe, among other scholars, I know this was not the case, even in Chicago, yet Carroll’s assertion speaks to the paucity of peers and opportunities, projecting a profound sense of accomplishment despite prejudicial circumstances. Moreover, in listing her gender and race, she gives reasons for patronizing her studio that correspond with the development of many “Don’t buy where you can’t work” or “Double your Dollars” campaigns that sought to thwart racist businesses while unifying diverse segments of African American populations.[21]

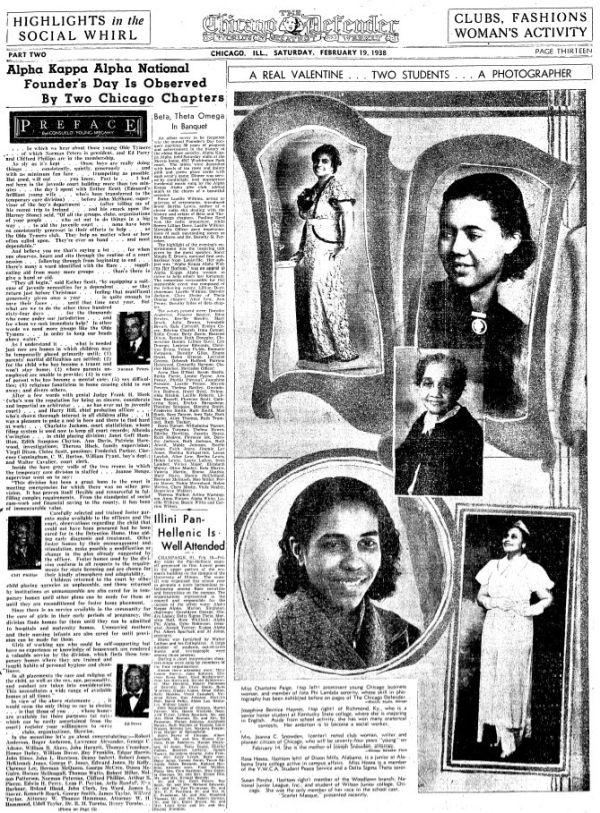

Carroll’s self-presentation extends beyond her business card and portrait as her likeness was also frequently featured in the pages of the Chicago Defender, one of the most widely circulated African American newspapers during the 1920s-1930s (fig. 3).[22]

Fig. 3. Detail, Electric Studio portrait of Charlotte Paige Carroll. Source: A

Real Valentine … Two Students … A Photographer, in: The Chicago Defender,

February 19, 1938, p. 13

For a special section celebrating Valentine’s Day, Carroll’s portrait, credited to Electric Studio, was published with the portraits of several other Black women, representing a range of ages, professions and social ambitions. Attentive to contemporary fashion and the glamor aesthetic that marks portraiture from the 1930s, Carroll embodies Electric Studio’s promise for an “opportunity to be photographed beautifully and cheaply awaits you NOW.” Given the dearth of positive representations of Black women in the mainstream media as well as the oft voiced lament that white photographers “botched” the lighting of African American skin tones, this promise resonates deeply.[23] Additionally, Electric Studio sought to make photography economically accessible, offering various specials and discounts, crossing over the intersectionality of gender, race and class.

Collaged into a half-page spread, Carroll’s full-length portrait and pose evoke a sense of self-possession and the accompanying caption acknowledges her as a “prominent young businesswoman,” who is a member of Iota Phi Lambda sorority and “whose skill in photography has been exhibited before on the pages of the Chicago Defender” (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Full page featuring: A Real Valentine … Two Students … A Photographer. Source: The Chicago Defender, February 19, 1938, p. 13

Reports on Carroll’s life and character also appear in other Black media outlets such as the “Light: America’s News Magazine,” where she is described as an “industrious and bright eyed young lady.”[24] One journalist of the “Chicago Defender” not only affirmed that Carroll is a “hard worker and a good business woman”, but also recognized the role that gender plays in her efforts to prove that “there are some things that women can do as well or better than men.”[25]

These snippets, pulled from the broader context of reporting on women’s activities in Chicago, give some insight as to the expectations of gender that Carroll and other women from her era negotiated, as well as some inkling as to how she sought to define her personal and professional self. I learned of her impending marriage, continued interest in playing the violin, as well as where she shopped to purchase groceries for her husband’s dinner – details that in some ways harken back to the nineteenth century model for the “New Negro Woman”. As imagined by illustrator John Henry Adams, such a woman should be “an admirer of Fine Art, a performer on the violin, and the piano, a sweet singer, a writer – mostly given to essays, a lover of good books, and a home making girl.”[26] As a graduate of the prestigious Fisk University, Carroll would have been schooled in the gendered etiquette conventions of the day, yet to what extent the expectation to perform propriety influenced her life calls for some speculation. Certainly, the owning and operating of a business is a counterpoint to a traditional idea of “homemaking.”[27]

The tone and fragmented nature of these biographical “facts” leaves an incomplete sense of personhood – begging the question as to what other sources might expand our understanding of her business acumen, perspective on the role of photography, and her advocacy of women’s professional engagement. As scholar Katherine Lennard argues, “Remembering the names is only part of the work – it is also the practice of recording and conveying the particular ways that individuals navigated constrained circumstances” that affords an expanded understanding of the photographic image.[28]

Photography as a Social Process: Electric Studio’s Community and Clientele

To reflect historically requires a broader consideration of sources that may have proved inspirational for Carroll and her peers. Following a speculative thread and looking to the wide array of Chicago’s successful Black female entrepreneurs, such as Mayme Lee Clinkscale, the proprietress of the popular Ideal Tea Room, or beautician Marjorie Stewart Joyner, who invented the permanent wave machine and owned a shop near Electric Studio, perhaps Carroll not only found inspiration, but also sought to document their contributions, recognizing the social capital gained through publishing one’s photograph in the Black media. Additionally, during this period, Chicago social and cultural organizations generated numerous photographically rich compendiums, such as the Washington Intercollegiate almanacs, that addressed women’s professional activities among other topics.

Might the texts written by women for what was colloquially referred to as “The Wonder Books” have influenced Carroll’s perspectives on what was possible to achieve and express? Published in 1927 and 1929, this two volume historic compendium presented African American contributions to culture, labor, commerce and education.[29] Perhaps essays written by trailblazers – such as social worker Florence “Frankie” Adams, lawyer and later delegate to the United Nations Edith Sampson, or civic leader Irene McCoy Gaines – that urged Black women to cultivate “job respect,” to advocate and to organize not only informed Carroll’s aspirations but also how the patrons of Electric Studio came to know themselves and how they wanted to be represented. Indeed, portraits by Electric Studio became a form of advocacy, presenting the particulars of an individual’s achievement as well as a collective growing consciousness.

Commissioning a portrait testifies to self-worth and self-imagination. These images reflect choices not only made by photographers and subjects but also by viewers, publishers, collectors, archivists, and future researchers who encounter them. In publishing their portraits in the pages of the “Chicago Defender” and other news media, women such as educator Oneida Cockrell or YWCA chairman Freda Cross gave over their likenesses to the public sphere, participating in the scaffolding of the politics of respectability, modeling the possibilities of economic mobility and personal achievement (figs. 5-8).

Fig. 5. Portraits by Electric Studio. Sources: Modiste, in: The Chicago Defender March 30, 1935, p. 22; Wins Praise, in: ibid., March 16, 1935, p. 6; Speaker, in: ibid., April 22, 1933, p. 6; Honored, in: ibid., October 19, 1935, p. 11

Their mediated presence allows sight to become a site, a place to see and be seen, that served themselves as well as their respective communities. Their determination to “win praise” and be “honored” for their professional achievements brought them to photography and specifically to Electric Studio. Once there, waiting for the arrangement of camera and lights, might these women have engaged in conversation around their respective committee work, discussing the fashions, events and concerns of their lives? The sites of their lives – Forum Hall, the Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments Nursey, Percy Sims Mortuary and the YWCA – were also featured in the pages of the “Defender” and served as an anchor for the possibilities represented by their likenesses and the brief reports on their accomplishments. Further, by reconnecting their likenesses with the site-specific histories of photography, it is possible to move away from the problematic generalizations within the category of Black vernacular photography and into a more expansive understanding of the specific roles that Black women played in the visualization of modern subjectivity.

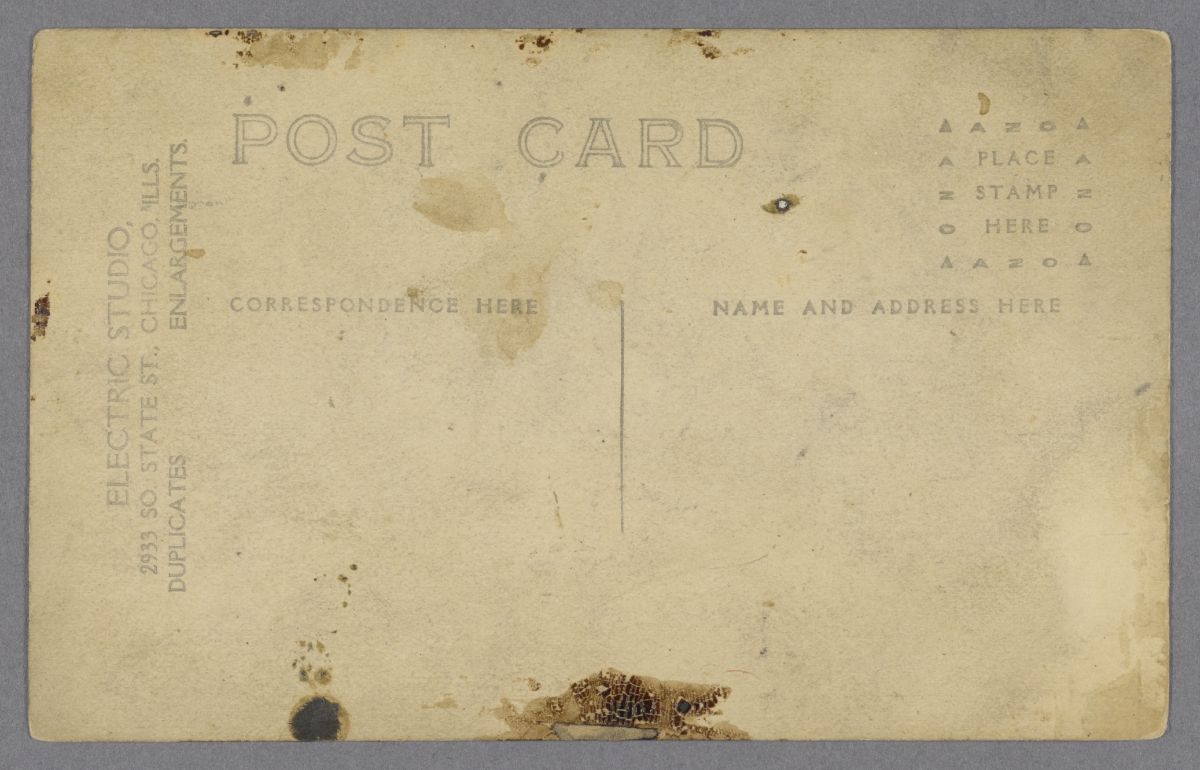

With this perspective, cobbled from both direct and indirect references to Carroll and Electric Studio, might it be possible to approach the vernacular images that remain unidentified in the archive differently? Take one of the most enigmatic images in the Robert Langmuir collection – a portrait of two men and two women in the Electric studio (figs. 9-10).

Fig. 6/7. Electric Studio, Postcard, recto and verso, subjects unknown. Source: Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection, Emory University, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

The men, dressed in suits and holding their hats, shake hands while standing on the exterior side of a window while two women, standing on the interior, lean out slightly, directing their gaze toward the man that is closest to them. The women are also stylishly dressed for the occasion, poised in a seemingly flirtatious manner; in fact, the whole scene seems quite staged for the camera. Within the finding aid, this photograph is categorized as “Portraits, couples,” an apt, but fairly meaningless descriptor. It’s the verso that compels a further consideration within skein of photographic purpose generated by Carroll and her colleagues. In addition to an imprint bearing the studio’s address offering duplication and enlargement, the back of the photo reveals it to be a postcard. By the 1910s, printing photographs on postcard paper was quite common, but it bears a unique meaning for the image and the intention of its subject and maker.

By making this photograph a postcard, a mode of communication with the potential of exchange between two parties, Electric Studio and their patrons engage in the social role of photography. As a postcard, the photograph insists on the possibilities of exchange, reception and response, portending a shift between time and place that reflects the expansion of modern travel opportunities, an especially resonant history for African Americans who relocated to northern cities in the United States during the Great Migration.[30] Yet this card was never posted. Instead it was collected, preserved and valued for what it conveyed in terms of social mores, humor and memory of being photographed.

Now, encountered in the archive, this image moves from the realm of the private into the realm of the public like the portraits printed in the media. As such, it serves as an assertion of Black spectatorship, a demonstration of Black people looking at representations of themselves and engaging in a dialectical relationship with the photography.[31] The reproduction and circulation of such portraits establishes photography as a social practice through which one not only comes to see and know oneself, but also how that self is perceived by others. As scholar Leigh Raiford argues, “black photographic portraiture functioned not simply as a private sentimental memento but within the shadow archive of black representation, the process of black visual self-representation also produced public documents of African American citizenship and middle-class belonging.”[32]

Reimagining the Archive

Research is an accumulative process with one facet leading to another, but not necessarily in a teleological progression. It is not just a question of where to look, but also how to interpret and contextualize the relationships between individuals, institutions and their representation in the media. In my initial attempts to trace the impact and meaning of Charlotte Paige Carroll’s photography, I have drawn from the specific to the general, from the micro to the macro, seeking to understand the role that both absence and presence play. It is an imperfect and incomplete knowing, yet for now, serves as a suggestive invitation for what is to come. As reminded by cultural historian Stuart Hall, identities are “far from being grounded in a mere ‘recovery’ of the past, which is waiting to be found and which, when found, will secure our sense of ourselves […] position[ing] ourselves within the narratives of the past.”[33] As such, it is possible to understand Carroll’s assertions of agency and presence not only within her respective era, but also within our current moment, imagining future resonance. Carroll’s presence in the archive and her impact on the visualization of Black subjectivity will continue to evolve, especially as scholars consider the contingent and relational histories of Black communities. I think of this process as a listening, a response to the expansive category of the vernacular, bringing into everyday speech and the cadence that emphasizes connectivity of the past, present and future.[34]

This research is part of an ongoing multi-faceted digital humanities project in collaboration with renowned photo historian Deborah Willis, called “Say It with Pictures”, that redresses the work of African American commercial photography studios active in the 1890s through the 1930s in Chicago. Our project will be the basis for an exhibition at the Newberry Library in 2027 that will present photographs and publications from over sixty-five studios as well as contemporary artists’ responses to these important histories, allowing us to reimagine the connections and expand our understanding of the history and visual representation of Black lives.

[1] For insights on the motivation, process and collaboration that resulted in Moutoussamy-Ashe’s groundbreaking research, see Kalia Brooks, An Oral History with Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, in: Bomb Magazine (September 11, 2014), online https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2014/09/11/jeanne-moutoussamy-ashe/ [08.10.2025].

[2] Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, in: ARTnews 69.9 (1971), pp. 22-39, 67-71, republished in: ARTnews, 30.05.2015, online: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/retrospective/why-have-there-been-no-great-women-artists-4201/ [08.10.2025].

[3] Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers, New York 1986, republished 1993.

[4] Valencia Hollins Coar, The Black Photographer: An American View, Chicago 1985; Deborah Willis, Black Photographers, 1840-1940: An Illustrated Bio-Bibliography, New York 1985; idem, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present, New York 2000; Deborah Willis/Carla Williams, The Black Female Body: A Photographic History, Philadelphia 2002.

[5] For an expansive understanding of the impact of this first international movement led by African Americans, see Denise Murrell (ed.), The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, New York 2024.

[6] Antoinette Burton, Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and Writing of History, Durham 2005, p. 7, online https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/989/chapter/147400/IntroductionArchive-Fever-Archive-Stories [08.10.2025].

[7] Pierre Bourdieu et al, Photography: A Middle-brow Art, Stanford 1990. As Bourdieu notes, the practice and aesthetics of photography were determined by social class and followed “the canon of traditional ‘aesthetic.’” Ibid., p. 16.

[8] Brian Wallis, The Dream Life of a People: African American Vernacular Photography, in: idem, African American Vernacular Photography: Selections from the Daniel Cowin Collection, New York 2005, pp. 9-10. Geoffrey Batchen’s considerations of the practices and morphology of the vernacular have also framed my approach, see idem, Vernacular Photographies, in: idem, Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History, Cambridge 2000, pp. 57-80.

[9] Wallis, The Dream Life of a People, p. 10.

[10] Daniel Cowin was a trustee of the International Center of Photography from 1987 until his death in 1992. A banker by profession, Cowin donated more than 1600 photographs, which documented African American life from the mid-nineteenth century through the 1950s. The ICP website described the collection as offering “a glimpse into the rarely seen everyday lives of African Americans in a variety of genres and poses, formal studio portraits, casual snapshots, images of children, images of uniformed soldiers, wedding portraits, and ‘Southern-views’ made for tourist consumption. While some of the sitters are celebrities of the day, the majority are unnamed Americans simply posing for their portraits.” Online: https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/collections/african-american-vernacular-photography [08.10.2025]. The Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection was acquired by Emory University in 2012 and consists of more than 12,000 photographs depicting African American life from as early as the 1840s through the 1970s. Langmuir, a rare book dealer from Philadelphia, began collecting the manuscripts and art of Black writers and artists twenty years ago.

[11] As Karen Cross and Julia Peck point out, the archiving of the vernacular fractures the “normalizing of existing power relations,” allowing for “the archive – and the terms under which it reproduces knowledge – becomes open to scrutiny and is confronted with its own history, the memory of its inclusions and exclusions.” See idem, Editorial: Special Issue on Photography, Archive and Memory, in: Photographies 2 (2010), pp. 128-129, online https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17540763.2010.499631#d1e136 [08.10.2025].

[12] For the influence and context of the use of photography by Douglass and Truth see Maurice O. Wallace/Shawn Michelle Smith (eds.), Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity, Durham 2012; and Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance, Chicago 2015.

[13] Saidiya Hartman, Venus in Two Acts, in: Small Axe 12.2 (June 2008), pp. 1-14, here p. 11, online https://read.dukeupress.edu/small-axe/article/12/2/1/32332/Venus-in-Two-Acts [08.10.2025].

[14] Ibid., p. 14.

[15] Regardless of whether she created the photograph or served as the subject, like Sojourner Truth, Carroll becomes an active agent in the construction of her image as evidenced in her decision to use it on the business card. See Emily Brady, „Shutterbug?”: Black Women Photographers and the Politics of Self-Representation, in: Ellery E. Foutch (ed.), Producing and Consuming the Image of the Female Artist, in: Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 9.1 (Spring 2023), online https://journalpanorama.org/article/shutterbug/ [08.10.2025].

[16] For the history of the “New Negro”, see Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Trope of the New Negro and the Reconstruction of the Image of the Black, in: Representations 24 (Fall 1988), pp. 129-155.

[17] Among the first definitions and visualizations of the “New Negro” was John Henry Adams, Rough Sketches: Study of the Features of the New Negro Woman, in: The Voice of the Negro 1.8 (August 1904), pp. 323-326.

[18] Andrea Nelson/Mia Fineman, Preface, in: idem (eds.), The New Woman Behind the Camera, Washington D.C. 2021, p. 15.

[19] Deborah Willis, Picturing the New Negro Woman, in: Barbara Thompson (ed.), Black Womanhood: Images, Icons and Ideologies of the African Body, Seattle 2008, pp. 227-245, here p. 228.

[20] J.C. Schlink may be the son of Charles Joseph Schlink, a photographer who first worked in Fort Wayne Indiana in 1900, then moved to Kalamazoo, MI in 1913, then is listed as having a studio at 3342 S. State Street in Chicago in 1918. How Carroll came to be part of the business is not yet known. See Clayton A. Lewis (ed.), Directory of Early Michigan Photographers, David V. Tinder, Ann Arbor 2013, online https://clements.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/files/tinder_directory.pdf [08.10.2025]. As of yet, Schlink’s racial identity is not clear, though his politic seems progressive given his membership in the Mid-South Side Chamber of Commerce which sought to eliminate “the so-called racial and religious problems as they effect mercantile progressiveness, property values, and labor conditions” see Mid-South Side Chamber of Commerce, in: The Broad Axe August 13, 1927.

[21] For this movement’s impact on class-consciousness see Davarian Baldwin, Chicago’s New Negroes: Modernity, The Great Migration, and Black Urban Life, Chapel Hill, NC 2007, pp. 237-240. St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton credit the “Double-Duty Dollar” doctrine to Dr. Gordon B. Hancock as published in his serial Between the Lines. See idem, Black Metropolis. A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, Chicago 1993, p. 430.

[22] By the late 1920s, the “Defender” had a circulation of 260,000 including international subscriptions. See Ethan Michaeli, The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America, New York 2016.

[23] In his often-cited article “Photography”, W.E.B. Du Bois posed the question, “Why are there not more colored photographers?”, seeking to encourage more African Americans to pursue the profession and improve the lighting technique to best represent variable skin tones The Crisis 26.6 (October 1923), pp. 249-250.

[24] It Won’t Be Long Now, in: The Light: America’s News Magazine 24 (September 9, 1928), p. 18.

[25] Allan McMillan, 47th Street-Chicago: A Columnist Crashes in on a Movie Star’s Party, in: The Chicago Defender (July 15, 1933), p. 15.

[26] Adams, Rough Sketches, p. 326.

[27] Jack Ellis, The Orchestras, in: The Chicago Defender (December 10, 1932), p. 5, Allan McMillan, Hi Hattin‘ in Harlem: Memos of a Roving Reporter, in: The Chicago Defender (August 1, 1936), p. 10, Elizabeth Galbreath, Typovision, in: The Chicago Defender (January 25, 1941), p. 16.

[28] Katherine J. Lennard, Histories ‘Made out of Pictures and Words Just Kept’, in: Art Journal 1 (June 16, 2023), online https://artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=18176 [08.10.2025].

[29] For more information on the impact of these publications see Adam Green, The Rising Tide of Youth: Chicago’s Wonder Books and the ‘New’ Black Middle Class, in: Burton J. Bledstein/Robert D. Johnston (eds.), The Middling Sorts: Explorations in the History of the American Middle Class, New York 2001, pp. 239-255. Although Electric Studio was not among the photographers who contributed to this publication, several of the studios employed women, including Woodard’s Studio that promoted the talents of Lottye Hale Jacobs, who established her own studio in Chicago’s South Center building. See: Pistol Shots Upset Peace Along Stroll: 47th St., South Pkwy., Is Battle Front, in: The Chicago Defender, August 6, 1932, p. 4.

[30] As noted by Christraud M. Geary and Virginia-Lee Webb, the post-card establishes “a relationship of obligation between the sender and the receiver.” See: Introduction, in: idem, Delivering Views: Distant Cultures in Early Postcards, Washington DC 1998, p. 4. Gear and Webb cite Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Baltimore/London 1984, p. 138.

[31] Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle, Chapel Hill 2011, p. 14.

[32] Ibid., p. 15.

[33] Stuart Hall, Cultural Identity and Diaspora, in: Jonathan Rutherford (ed.), Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, New York 1990, pp. 222-237, here p. 225.

[34] My consideration of the possibilities of vernacular as speech and the ways that images speak is influenced by Fred Moten, In the Break: the Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, Minneapolis 2003, and Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images, Durham 2017.

This article is part of the theme dossier “Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive,” edited by Christina Benninhaus and Mary Jo Maynes.

Theme Dossier: Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive

Zitation

Amy M. Mooney, Customs and Declarations: Research Strategies for Uncovering the Hidden History of a Black Woman Photographer, in: Visual History, 27.10.2025, https://visual-history.de/2025/10/27/mooney-customs-and-declarations/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2955

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Eine Nutzung ist für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in unveränderter Form unter Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de