Gender Battles in Women’s Comics of the Second-Wave Feminist Era

Visualizing Women’s History through Women’s Comics

The emergence of second-wave feminism was linked to the youth rebellions of the 1960s and 1970s in the U.S., Europe, and Latin America. Older women found paths to feminism through various channels, but younger women often turned to feminism as a result of their experiences of marginalization in male-dominated social-movement organizations of the era, and their critique of the organizations’ inegalitarian gender dynamics.[1] During roughly the same time period, in many sites across the globe, adult-oriented comics began to express serious political and social critiques by adapting the comic form in a range of new sub-genres and for a variety of new purposes. Comic artists produced political satires; they pirated classic comic heroes to deliver new political messages; and they wrote dystopic fantasies. In addition, they produced graphic memoirs of a quite serious sort that depicted their authors’ experiences in the past, including traumatic pasts.

In this political and cultural context, as women challenged patriarchal relations within social movement organizations, or seceded from them to form women-only groups, women artists turned to the comic form as a new vehicle for self-expression. Women artists increasingly deployed the comic form to criticize the sexism that was all too often expressed graphically in the very comics that were so much a part of the 1960s youth cultural rebellion – most notably in “underground comics” in the U.S.[2]

Until very recently, the work of women comic artists has rarely been incorporated into historians’ narratives of second-wave feminism. However, for more than a decade now, from other disciplinary perspectives, literary critics and art historians such as Hillary Chute, Susan Kirtley, and Małgorzata Olsza have been documenting and analyzing the history of women’s engagement with the comic form and connections between feminism and comics.[3]

Based on scholarship from across the disciplines, this article calls attention to examples of gender-themed comics from the era of second-wave feminism with the aim of bringing them into our thematic dossier’s wider discussion of “seeing” the history of women, gender, and sexuality through visual sources. I will suggest how a focus on women’s comics brings new perspectives to historians’ understanding of second-wave feminism, its origins, and its contestations. I will begin by looking at scholarship on some of the key moments in the production and reception of women’s comics in the U.S., putting this in comparative context by looking a few examples from France. I then discuss American feminists’ embrace of and objections to women’s comics, as well as rifts within the community of women comic artists and readers of comics. I will then briefly exemplify two themes that women comic artists explored – body image and motherhood – pointing to the complicated place of these themes in relationship to the broader feminist critique. I will end with a brief note on legacies of and pushbacks against second-wave feminism as they appear in the realm of comics.

Women Producing Comics in the Context of Second-Wave Feminism

The comic artists who worked in the early mainstream arenas of Sunday and daily newspapers and the short inexpensive “comic-book” form in the U.S. up through the mid-twentieth century were nearly all men. This continued to be the case as comics expanded thematically and stylistically to bring political and social critiques, historical analyses, and other new sub-genres to adult audiences, first in postwar Europe and then in the U.S. A very small number of women artists, most notably Claire Bretécher in France, had established careers by the 1960s. According to Bas Schuddeboom, “Bretécher was a pioneer in many ways. During the 1960s, she was the first female comic artist with a prominent spot in several Franco-Belgian comic magazines.”[4]

In the U.S., the rebellious “underground comix” movement beginning in the 1960s might have seemed to be a logical point of entry for women into the field, but women comic artists were marginalized – first, simply as women professionals, and additionally, because of the highly visible sexism that pervaded the universe of male underground comic artists.[5] In her book Graphic Women, which examines autobiographical comics by several female creators, Hillary Chute links the misogyny of underground comics with the emergence of a feminist critique:

“The growth of the underground commix movement was connected to second-wave feminism […] if female activists complained of misogyny of the New Left, this was mirrored in underground comics, prompting women cartoonists to establish a space specifically for women’s work. It is only in the comics underground that the U.S. saw any substantial work by women allowed to explore their own artistic impulses.”[6]

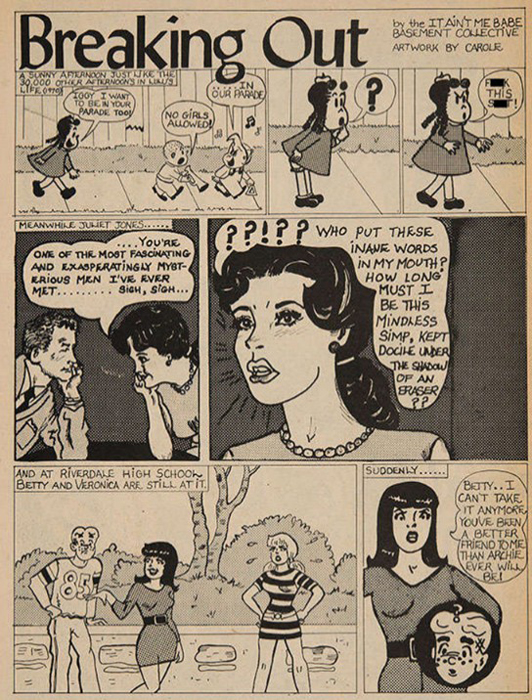

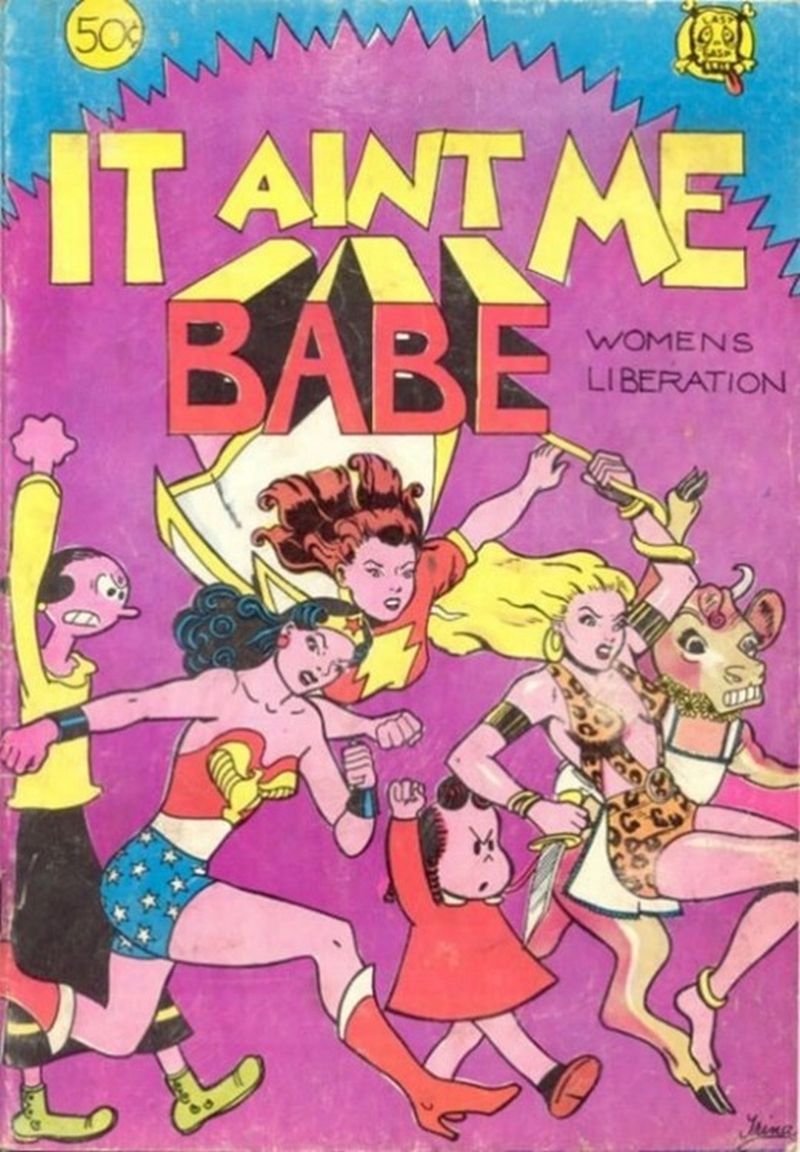

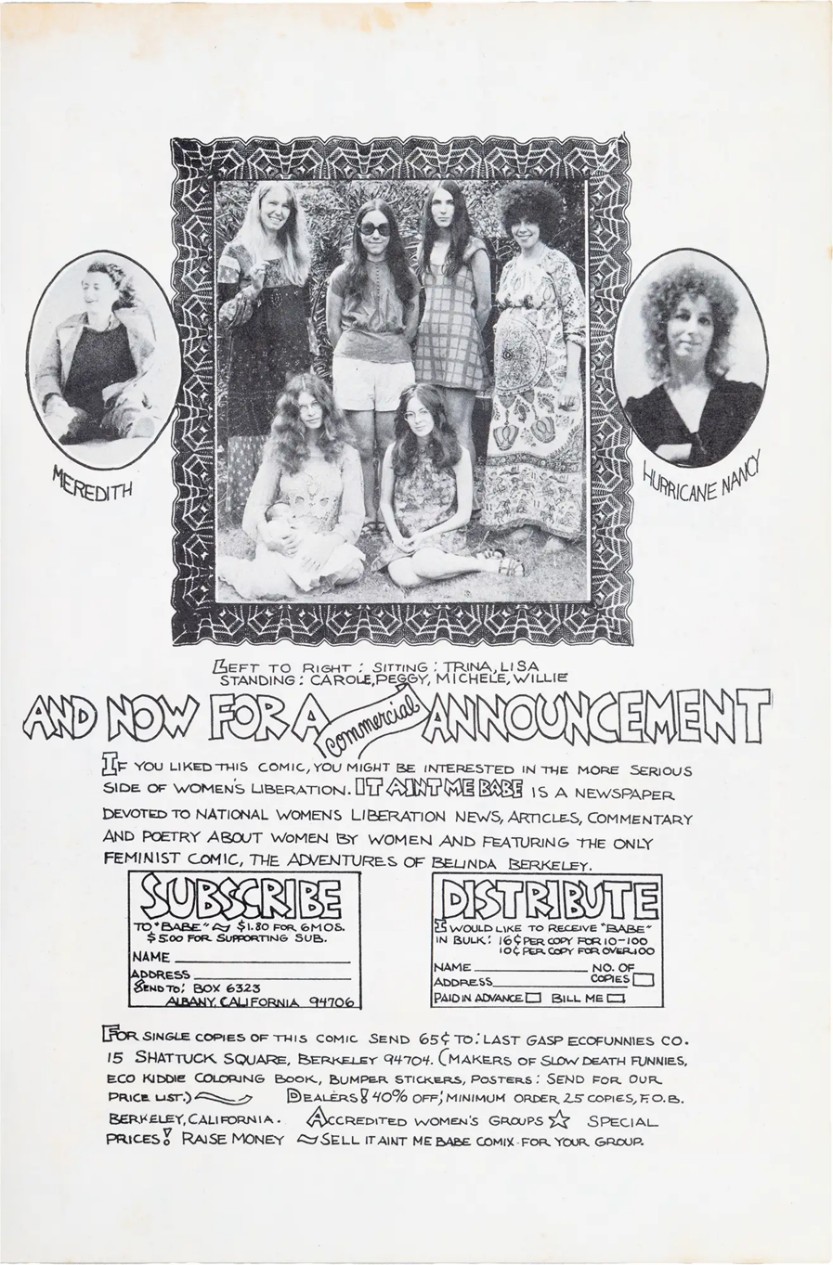

U.S. women comic artists experienced a breakthrough when the Berkeley-based editors of the short-lived feminist magazine called It Ain’t Me Babe, which had first appeared in January 1970, decided to publish a comic-form issue in July 1970; this special issue was co-edited and co-produced by Trina Robbins and Barbara “Willy” Mendes.[7] [See Figures 1, 2, and 3.] In this issue, in a comic called “Breaking Out,” women and girls normally drawn by male artists rebel against their characters’ limitations; their rebellion is succinctly summarized by Sagan Thacker: “Little Lulu walks down the street behind the boys. They shout, ‘No girls allowed!’ and Lulu responds with ‘Fuck this shit!’ Petunia Pig tells Porky to ‘Cook your own dinner[!]’ Betty and Veronica protest in front of their high school to get karate and women’s history classes.”[8]

Fig. 2. It Ain’t Me Babe Basement Collective and artwork by Carole, “Breaking Out,” It Aint Me Babe. July 1. Republished in “The Complete Wimmen’s Comix”, Vol. 1, Fantagraphics Books, Seattle 2016, p. 20 ©

Fig. 1. Trina, It Aint Me Babe. July 1970, Cover. Republished in “The Complete Wimmen’s Comix”, Vol. 1, Fantagraphics Books, Seattle 2016 ©

Figure 3. It Aint Me Babe. July 1970. Republished in in “The Complete Wimmen’s Comix”,

Vol. 1, Fantagraphics Books, Seattle 2016, p. 35 ©

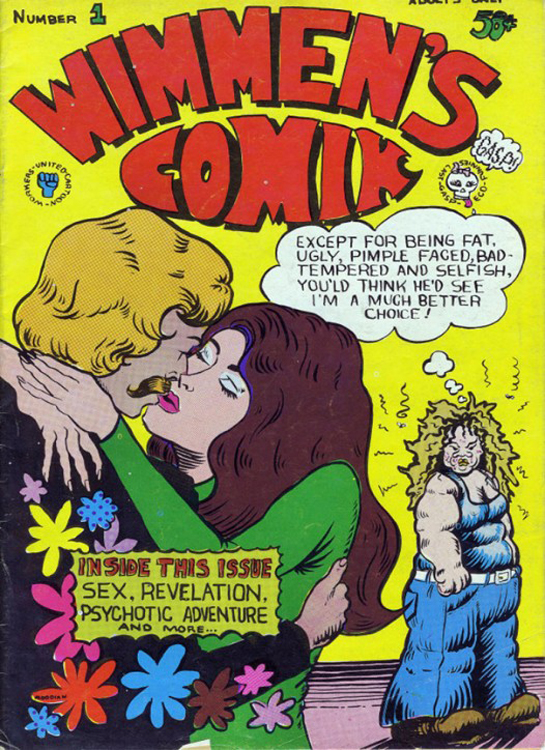

It Aint Me Babe stopped production after a year, but the comic issue was a success, and therefore many of the contributors created a new publication – Wimmen’s Comix – that was first published 1972 and would continue until 1992.[9] [See Figure 4.] One of the earliest contributors to this publication, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, recalled in a 2017 interview with Priscilla Frank: “I was very lucky. I arrived in San Francisco when the first edition of Wimmen’s Comix was getting put together. There were no women comics, so they would put anything in their book. So the first comic book I appeared in was Wimmen’s Comix.”[10]

Fig. 4. Patricia Moodian, Wimmen’s Comix, Number 1. 1972, Cover. Republished in:

“The Complete Wimmen’s Comix”, Vol. 1, Fantagraphics Books, Seattle 2016, p. 37 ©

Rifts over Women’s Comics and within the Comics Community

Among feminist audiences, Wimmen’s Comix met with a mixed reception. Thacker notes that many feminist reviews from the early 1970s praised the innovative comic form, thus “leading one to believe that comics […] were viewed as a valid form of feminist rhetoric within the [feminist] community.”[11] However, not all feminists were supportive of the new style comics as an appropriate feminist medium. Susan Kirtley points out that “in a particularly hurtful example, the mainstream feminist magazine Ms. refused to run Wimmen’s Comix ads,” not as a rejection of all comic forms, but rather as an explicit rejection of the particular visualizations and messages emerging from the feminist underground comics movement.[12] Kirtley argues that “while […] varying perspectives on Women’s Liberation differed in their philosophies and approaches, unfortunately, according to female cartoonists of the time, their efforts all seemed to be met with disdain by mainstream feminists […].” In an interview with Bill Sherman of The Comics Journal, Trina Robbins reflects that it was “really weird the way leftists and militant feminists don’t seem to like comix. I think they’re so hung up on their own intellect that somehow it isn’t any good to them unless it’s a sixteen-page tract of gray words.”[13]

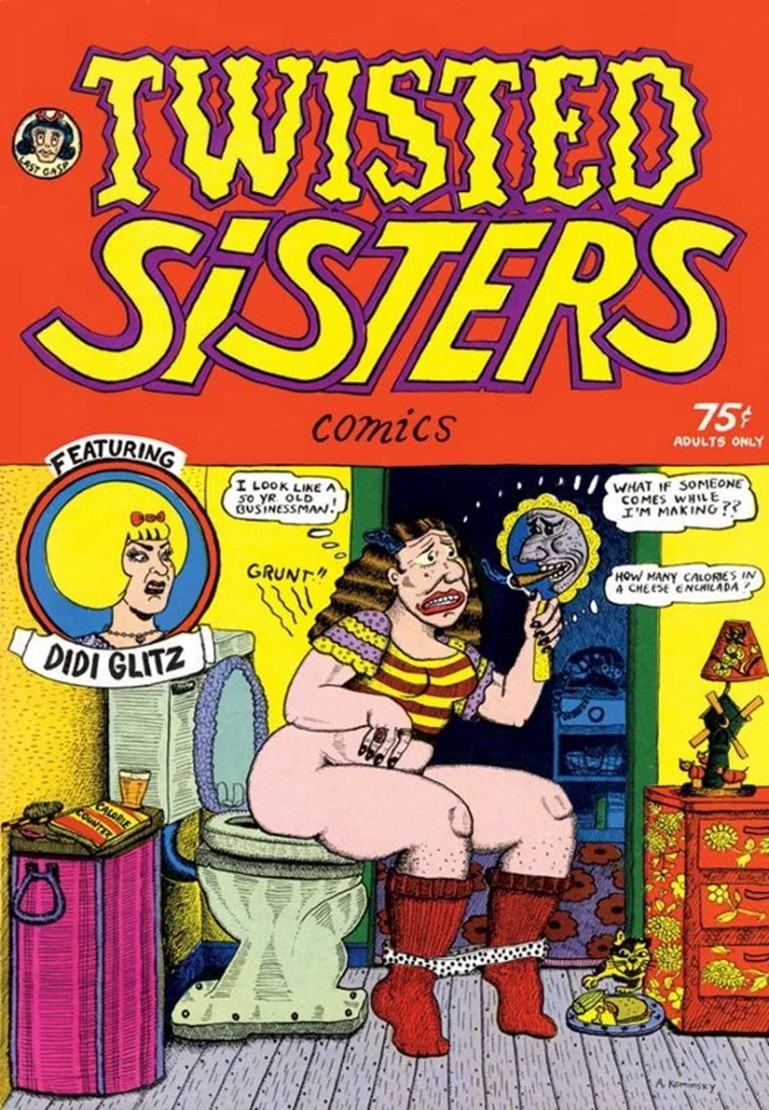

There were also skirmishes within the women comics community. Chute documents splits over both visual forms and ideological contents. She notes that Kominsky-Crumb, in particular, became “frustrated by what she perceived as an almost superhero-inflected glamorization of women under the auspices of feminism.”[14] The rifts within the Wimmen’s Comix group became publicly visible in 1976 when Kominsky-Crumb and Diane Noomin issued the breakaway comic Twisted Sisters, which deliberately “de-idealized” their images of women, a “decidualization” embodied on the cover of the first issue.[15] [See Figure 5.]

Fig. 5. Aline. Kominsky, Twisted Sisters #1. Cover, 1976 ©.

Source: Women in Comics Wiki [08.12.2025]

It is worth noting here that, throughout her career, Kominsky-Crumb always worked in the shadow of her more acclaimed male partner, the underground comic artist Robert Crumb, who was criticized by many feminists for the violence and misogynism of some of his work. Kominsky-Crumb’s relation with Robert, her attacks on some forms of feminism, as well as the nature of her depictions of women, continue to affect her legacy within art history and the history of feminism. According to Kirtley: “It would seem that some readers, perhaps uneasy with this explicit and grotesque sexuality from a female, have neglected Kominsky-Crumb’s impact, while others, possibly considering her an interloper in the underground comix scene, willfully ignore her contributions.”[17]

Inclusions and Exclusions

As the previous section makes clear, there were major disagreements among women comic artists of the second-wave feminist era, and also among feminists, about the use of the genre as a tool for expressing women’s perspectives. Moreover, there were other problems parallel to those that troubled the women’s movement more generally. All of the artists and editors associated with Wimmen’s Comix were white. Black feminist protests over the failure of many second wave feminist organizations to grapple with racism came to the fore in 1977 with the publication of the Combahee River Collective Statement by a collective of Black feminists who had been meeting together since 1974. In the statement, they called attention early on to the dynamics or racial exclusion or marginalization in the movement:

“A Black feminist presence has evolved most obviously in connection with the second wave of the American women’s movement beginning in the late 1960s. Black, other Third World, and working women have been involved in the feminist movement from its start, but both outside reactionary forces and racism and elitism within the movement itself have served to obscure our participation.”[18]

As far as I can tell, the presumptions of whiteness prevailed in the community of women comics, as it did in mainstream feminist circles more broadly. I haven’t yet found evidence of Black women comic artists publishing in the peak decades of second-wave feminism. In terms of longer history, Deborah Whaley has brought to light the earlier work of Jackie Zelda Ormes, the first known Black woman comic artist, who was already publishing in the 1930s: “Ormes’s propagating of what I call ‘cultural front comics’ – from a Black female perspective – made legible the resistance to Black subjugation in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s.” However, Whaley’s documentation locates Ormes’s successors only in the 1990s and later. The first organization formed for the support and collaboration of Black women comic artists that Whaley documents was, significantly, named the Ormes Society, a web-based group founded in 2007.[19]

A similar argument could be made about the relative absence of diverse sexualities, to which Kominsky’s comment above alludes, even as she makes her pitch for heterosexual normativity as “sexy.” There were depictions of lesbian relationships in Wimmen’s Comix, but they were rare and overshadowed by the numerous and graphic depictions of women’s unapologetic engagement in heterosexual relations, a hallmark of the comic’s visualization of female emancipation, even as the images often criticized aspects of men’s approaches to their partners. Margaret Galvan has documented some of the tensions over sexuality and challenges from lesbian feminists to feminist heterosexism.[20]

Chute notes the work of a relatively early rebel from the norm, Mary Wings, who was “reacting specifically to the perceived heterosexism of Wimmen’s Comix” when, in 1973, “she self-published Come Out Comix […] and so created the first lesbian comic book.”[21] Other gay comics started to appear around the same time, including Roberta Gregory’s Dynamite Damsels (1976),[22] eventually inspiring a slightly later generation of lesbian feminist comic artists like Alison Bechdel, who started publishing Dykes to Watch Out For in 1983, and who eventually even published an episode in Wimmen’s Comix in 1987.

Glancing beyond the U.S.

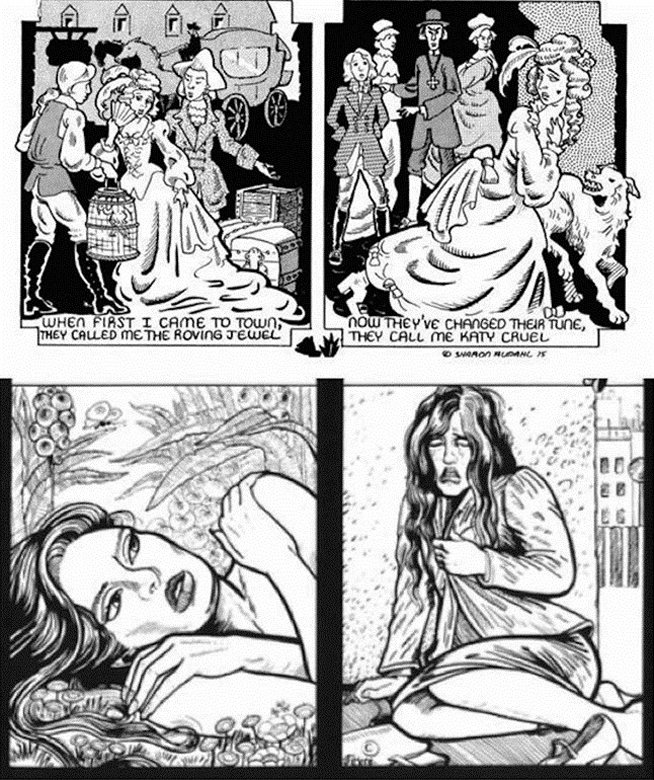

The focus here is mainly on the U.S. underground scene, but a quick glance across the Atlantic sets these developments in the U.S. in a comparative and transnational perspective. Feminist activists built international connections; these extended to the comic world. According to Leah Misemer, “women cartoonists […] went international in 1975 when Wimmen’s Comix published their ‘International Issue’ edited by Trina Robbins and Terre Richards.”[23] This issue included work by French cartoonist Cathy Millet, whose comics would also appear in the first issue of the French women’s comics publication Ah! Nana in 1976.[24] The first issue also featured reprinted translations of comics that had first appeared in Wimmen’s Comix.[25] [See Figure 6.] Misemer’s research brings to light the place of comic artists in the history of transatlantic feminism: “Ah! Nana included comics by Italian, French, and English women […] alongside discussions of women in film, literature, theater, and television, positioning comics within a genealogy of contemporary feminist media that reached across the globe, from France to Canada and Russia to China.”[26]

Fig. 6. (Top) Sharon Rudahl’s “Katy Cruel”; (bottom) Fêvre and Clodine “Fastasme

et Réalité” (1978). Source: Leah Misemer, “Hands across the Ocean. A 1970s

Network of French and American women Cartoonists,” in: Frederick Luis Aldama (ed.),

Comics Studies Here and Now, New York 2016, p. 205 ©

Here we see an argument for taking comics into account in terms of the history of transnational feminism, even as the previous sections suggested their relevance for the history of feminism in the U.S. Both the nature of the wider French feminist movement, in particular, and its connections with the movements in the U.S. and elsewhere might look different if feminist comics were to be included as part of the historical evidence. For one thing, the status of the comic form in France (bande dessinée), which had become an accepted form of serious critique in intellectual circles by the beginning of the second-wave feminist era, offered more opportunities to women comic artists there. Misemer argues that American women comics “used their marginalized status to position comics as the inheritor of other, equally marginalized feminist media.” In France, however, women comic artists, who were able to draw on a tradition of “comics as a legitimate medium able to stand alongside literature, film, and drama,” were able to use “that accepted status to position comics as part of global feminist media from the 1970s.”[27]

Two Exemplary Themes as Visualized by Women’s Comics: Body Image and Motherhood

In their 2020 thesis on the reactions of feminist readers to comics of the second-wave era, Sagan Thacker calls attention to the theme of self-deprecation and points out that analysts of these comics have “noted that much humor in these books is based on the contrast between ideal, socially conditioned expectations and the disillusioning reality characters encounter.”[28] Many of the comics that satirize the contrast between ideal and reality center on body image, which visual representations such as comics can capture more readily than words alone.[29] We have already seen examples of the thematic centrality of body image as illustrated on covers of Wimmen’s Comix and Twisted Sisters. [Above, Figures 4 and 5.]

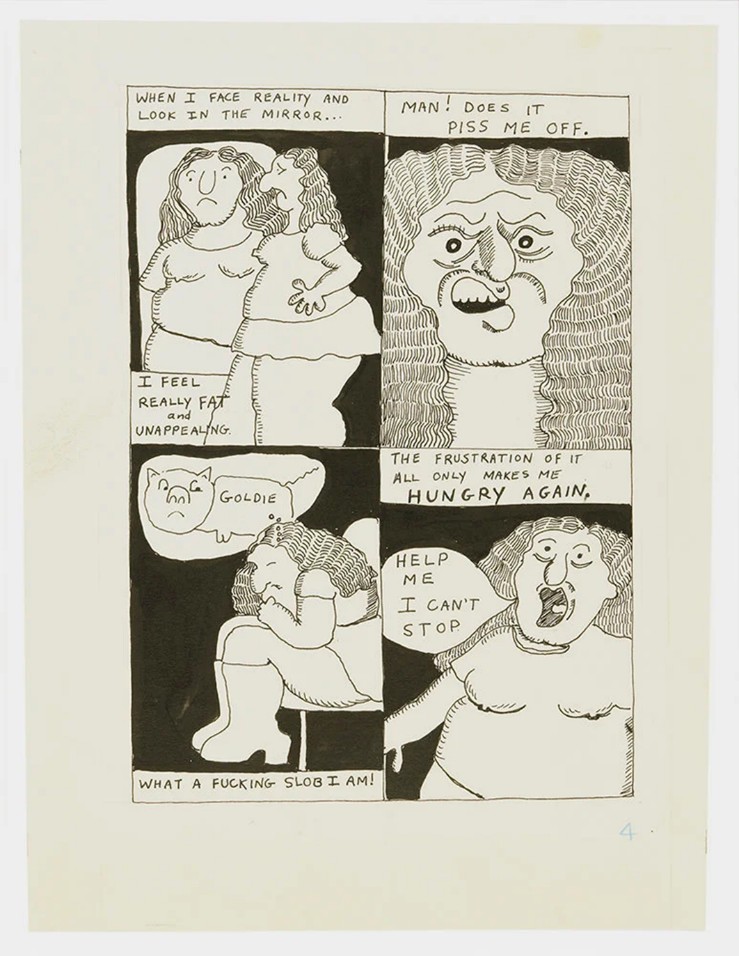

Many women comic artists of the era saw this as a central problematic that lent itself well to the comic form; as mentioned earlier, Kominsky-Crumb used representation of female body image precisely to counter the “superhero-inflected glamorization” of women of which she accused feminists.[30] But there seems to have been more going on than just de-glamorization. When Priscilla Frank asked Kominsky about her women characters who are “insecure, grotesque, sexual and sometimes self-destructive,” and asked, “Is she you?” Kominsky replied that “She is made up of exaggerated parts of me that I blow up and push to the maximum. I drew the most sordid, unacceptable parts of myself. I’m not as ugly as I draw myself. But when I was younger, that’s how I felt, so that’s what I drew.”[31] These self-doubts about body image appeared frequently in Kominsky-Crumb’s comics, notably in character “Goldie” in the 1970s. [See Figure 7.]

Fig. 7. Kominsky, from “Goldie,” p. 4. 1975 ©. Source: Priscilla Frank, “Meet the feminist

artist whose crass comics were way ahead of their time: Aline Kominsky-Crumb created

the first ever autobiographical comic made by a woman.” In: Huff Post, 14.02.2017 [08.12.2025]

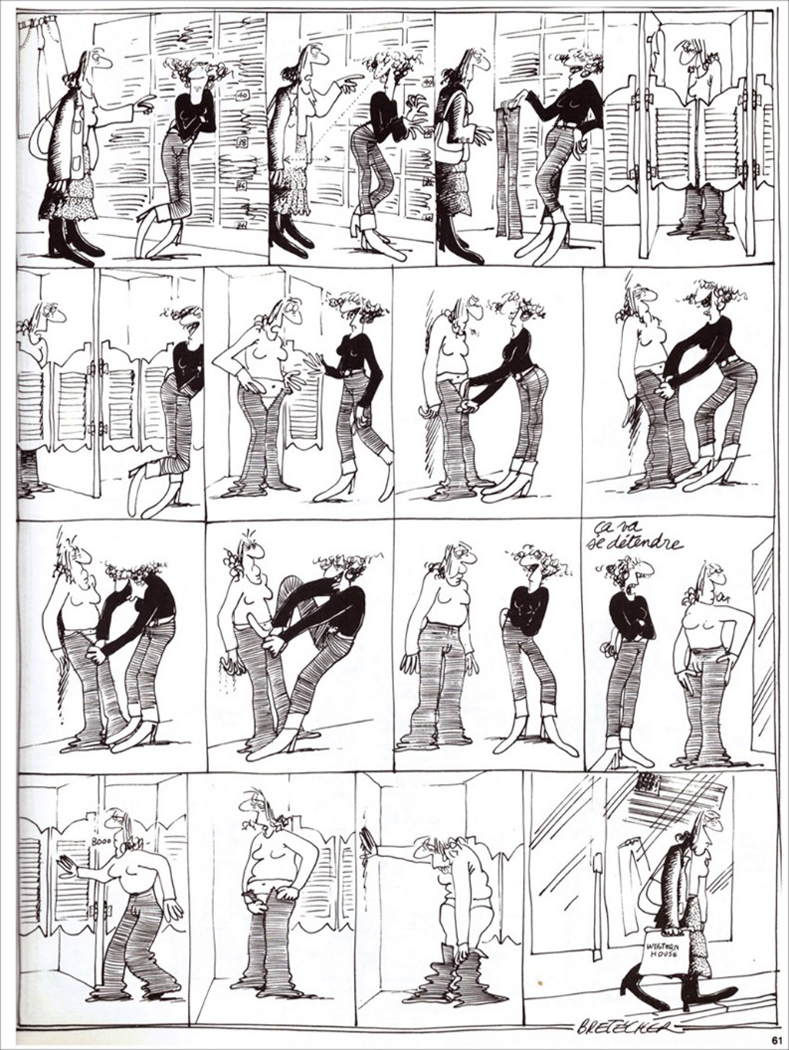

Fig. 8. Claire Bretécher, “Size 40 Narrow” (“Oh, it’ll give”), “Les Frustrès” 3,

Edité par l’auteur, 1978, p. 61 ©

Bretécher explored this among many other feminist themes even if, like Kominsky-Crumb, Bretécher had a troubled relationship to the feminist movement, usually rejecting the label feminist even when fans claimed her as their feminist inspiration. On a 2020 interview, she recalled that her reaction to feminist criticisms for her unflattering or crude drawings of women’s bodies, similar to the reaction faced by Kominsky-Crumb, was to point to her own deeply personal feelings about her body: “The body you have doesn’t count, what counts is how you feel. When it comes to me, well, I’ve always felt hideous, pitiful […] barely even civilized. Maybe it’s a little better now that I’m older. But when I was 26 or 27, it poisoned my life. Whenever some guy tried to pay me a compliment I would think he was making me into a joke. I’d respond aggressively and he would think ‘What a bitch!’”[32]

But if self-deprecation suited the satire intrinsic to some women comic artists, it was at odds with the aim of many second-wave feminists who preferred to criticize popular culture for its sexism and to create representations of women that would counter the sexism of mainstream culture. Michelle Arrow reminds us: “One project of second wave feminism was to create ‘positive’ images of women, to act as a counterweight to the dominant images circulating in popular culture and to raise women’s consciousness of their oppressions.”[33]

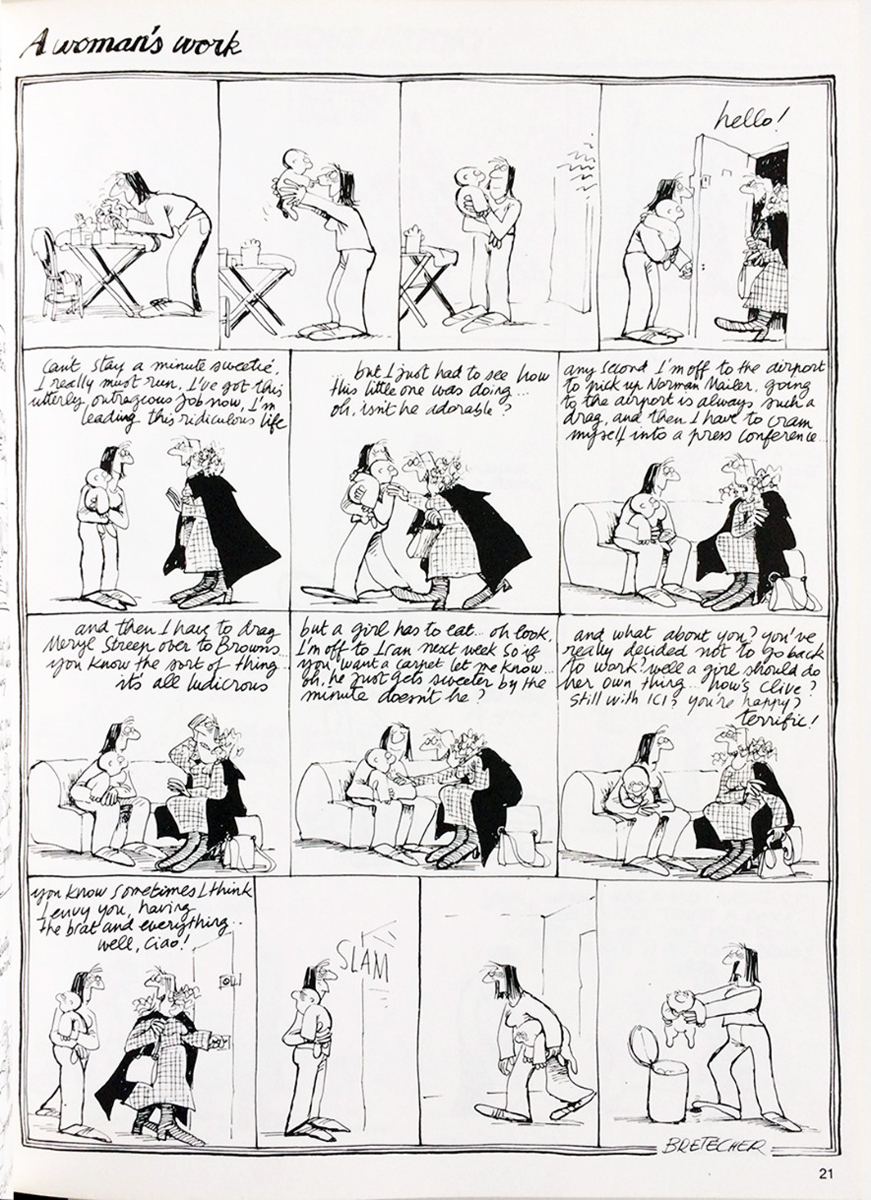

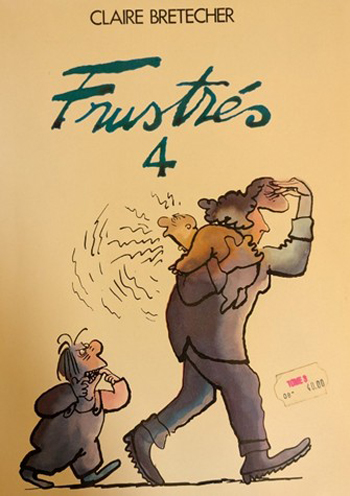

Like body image, motherhood was both exalted and satirized in the era of second-wave feminism. The general target of Bretécher’s satire in her most famous series – Les Frustrés – which she began publishing in 1975, was French bourgeois culture, including but not limited to its gender roles. Beyond issues of beauty and body, Bretécher also took up women’s work – including unpaid reproductive work. And, notably, the first issue of Les Frustrés included a shocking de-sacralization of motherhood, which pitted the daily life of a successful professional woman against that of her friend, the stay-at-home mom. [See Figure 9.]

Fig. 9. Bretécher, “A Woman’s Work,” in: idem, Frustration (English edition, 1982), p. 21.

Originally published in “Les Frustrés”, 1, Edité par l’auteur, 1975 ©. Source: The Slings &

Arrows: Graphic Novel Guide, “Claire Bretécher”, Review by Woodrow Phoenix,

https://theslingsandarrows.com/frustration/ [08.12.2025]v

Fig. 10. Claire Bretécher, Les Frustrés, 4, Edité par l’auteur, 1979, Cover ©

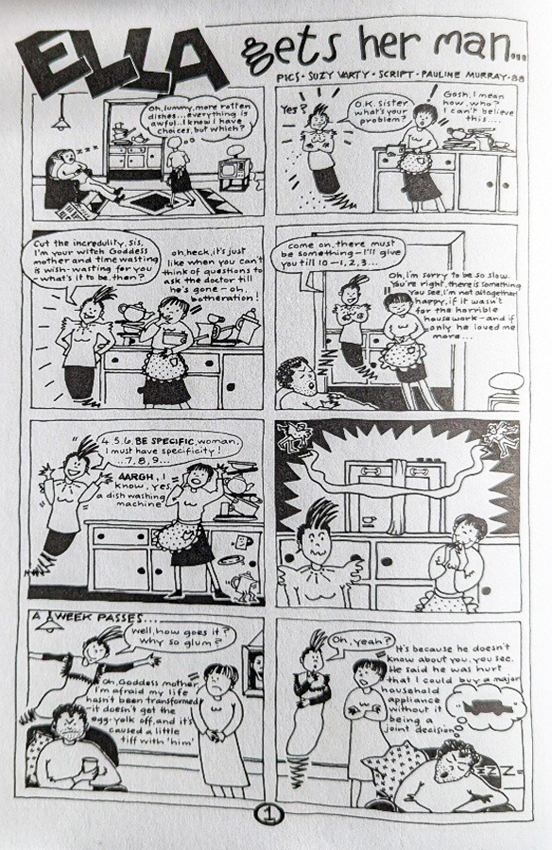

Gender inegalitarianism in workplaces was a strong theme in U.S. women’s comics, but, in contrast with Bretécher’s comics, Wimmen’s Comix took up the themes of domestic labor and motherhood only rarely. A few critiques of the drudgery of gendered household labor began to appear in the 1980s, for example Ella Gets Her Man by Suzy Varty and Pauline Murray, published in 1988. [See Figure 11.]

Fig. 11. Suzy Varty and Pauline Murray, “Ella Gets Her Man,” in: Wimmen’s Comix,

# 13, 1988. Republished in: The Complete Wimmen’s Comix, Vol. 2, Fantagraphics

Books, Seattle 2016, p. 502 ©

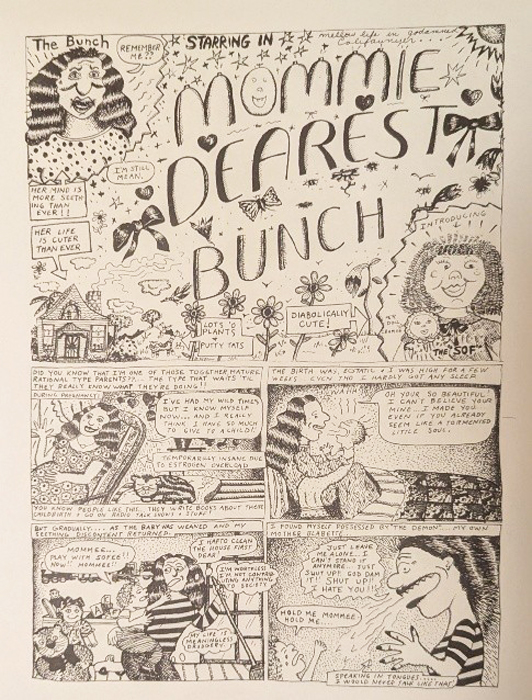

There were only a couple of examples of a “de-sacralization” of motherhood to be found in the issues of Wimmen’s Comix throughout its twenty-year run, one of which was published by Kominsky-Crumb in 1984.[34] [See Figure 12.] Kominsky-Crumb’s visual rant is as vivid as Bretécher’s but the relative invisibility to the creators and/or the audience for the critique of motherhood is apparent in comparison to its centrality to Bretécher and its apparent appeal to her readers.

Fig. 12. Aline Kominsky [Crumb], Mommie Dearest Bunch, Wimmen’s Comix, #9, 1984.

Republished in: The Complete Wimmen’s Comix, Vol. 2, Fantagraphics Books, Seattle 2016, p. 347 ©

As a historian interested in both women’s/gender history and visualization through the comic form, the connections I found are complicated and ambiguous and contentious in all sorts of interesting ways, including their implications for links between the personal and the political; the meanings of “feminism;” and the accomplishments, shortfalls, and legacies of the movement. Is it empowering for women to dwell on and make visual their “flaws” as a form of criticizing inevitable inabilities to live up to oppressive gender ideals? How do images – especially satirical and often grotesque images – act on viewers and go “beyond words”? How do images “embody” gendered subject positions, again in ways that words cannot? How might we compare the visual work of images that depict the rebelliousness of “breaking out” as opposed to the self-deprecation of “the failure to fit in?”

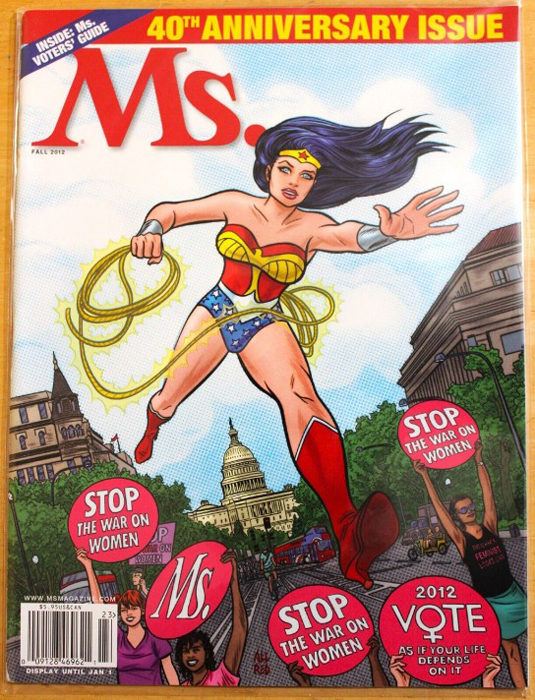

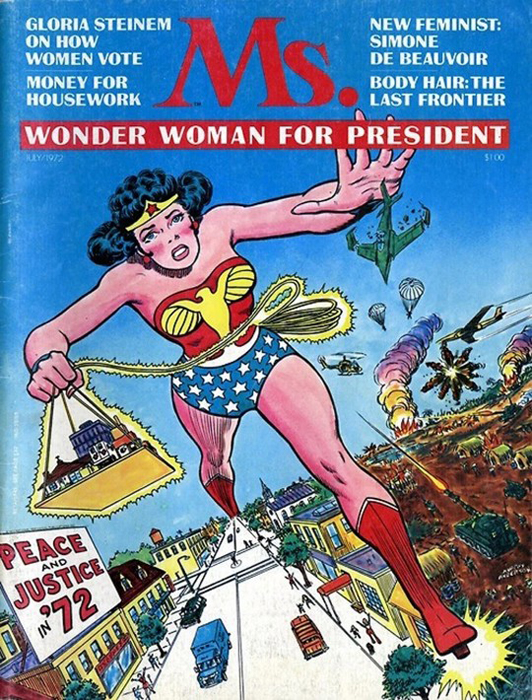

Of course, I haven’t even raised the question of the place of superheroine comics in all of this, a topic that has also been explored by feminist analysts of comics.[35] So I will end on this note. Recall that I noted that Ms. Magazine refused to carry ads for Wimmen’s Comix, rejecting these visual rebellions as unfit for mainstream feminist consumption? Despite the magazine’s rejection of that collective of women comic artists, the editors did not shy away from comics per se, as is apparent from the cover of their first issue and also two anniversary issues including one from 2012. [See Figure 13.] As the story titles on the cover of the first issue makes clear, the mainstream second-wave feminists who were represented here did grapple with oppressive body images and reproductive labor, but the comic heroine who most met with their approval seems to have been unperturbed by either of these problems.[36]

Fig. 13. “Ms. Magazine”, 2012, Cover ©. Source: Windy City Staff, Lynda Carter celebrates Ms. Mag’s 40th, in: Windy City Times, 03.12.2012, https://windycitytimes.com/2012/10/03/lynda-carter-celebrates-ms-mags-40th/ [08.12.2025]

Fig. 13. “Ms. Magazine”, 1972, Cover ©. Source: Windy City Staff, Lynda Carter celebrates Ms. Mag’s 40th, in: Windy City Times, 03.12.2012, https://windycitytimes.com/2012/10/03/lynda-carter-celebrates-ms-mags-40th/ [08.12.2025]

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank many people who have helped me to see history through comics, especially my co-panelists at the 2023 Berkshire Conference on Women’s History, the participants in the Fall 2023 discussion at the UMN Workshop on the Comparative History of Women, Gender, and Sexuality, and those who offered individual feedback including: Zornitsa Keremidchieva, Anna Clark, Lena Paulsen, Isabel Gellert, Karina Horsti, Christina Benninghaus, and Christine Bartlitz.

[1] One of the earliest formulations of the dynamic of women’s marginalization in 1960s social movement organizations, and their turn to feminism is Sara Evans, Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left, New York 1979. The global framework of these movements is explored in a special issue: American Historical Review 114 (2009), The International 1968, Parts 1 and 2.

[2] For an introduction to various aspects of the comic scene of this era, see: Jan Baetens/Hugo Frey/Stephen E. Tabachnick (eds.), The Cambridge History of the Graphic Novel, Cambridge 2018. For feminist comics in particular, the chapter by Susan Kirtley is especially insightful: “A Word to You Feminist Women”: The Parallel Legacies of Feminism and Underground Comics, ibid., Part II: 1978-2000, pp. 269-285.

[3] In addition to Kirtley, A Word to You Feminist Women, key works from these fields include: Hillary L. Chute, Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics, New York 2010; Sagan Thacker, “Something to Offend Everyone”: Situating Feminist Comics of the 1970s and ‘80s in the Second-Wave Feminist Movement, Senior thesis, The University of North Carolina at Asheville, 2020, online https://drive.google.com/file/d/1frESdfMyMWm5teThK3FRH6UZf_6pthy8/view [08.12.2025]; Małgorzata Olsza, Towards Feminist Comics Studies: Feminist Art History and the Study of Women’s Comix in the 1970s in the United States, in: Maggie Gray/Ian Horton (eds.), Seeing Comics through Art History: Alternative Approaches to the Form, London 2022, pp. 185-206.

[4] Schuddeboom also notes that Bretécher was “at the vanguard of a new wave of adult-oriented comics” and “one of the first comic artists to successfully venture into self-publishing. But most of all, she was the first satirist to focus on the behavior and conversations of both the adult and adolescent females.” Bas Schuddeboom, “Claire Bretécher,”, in: Lambiek Comiclopedia, 2020, https://www.lambiek.net/artists/b/bretecher.htm Downloaded 11/11/23 [08.12.2025].

[5] On this point, see Chute, Graphic Women, Kirtley, A Word to You Feminist Women, Thacker, “Something to Offend Everyone”, and Olsza, Towards Feminist Comics Studies.

[6] Chute, Graphic Women, p. 20. See also Evans, Personal Politics.

[7] Trina Robbins shared her memories of the production of the Wimmen’s Comix Collective in “babes and women”, in: The Complete Wimmen’s Comix, Vol. 1, Seattle 2016, pp. vii-xiii.

[8] Thacker, “Something to Offend Everyone”, p. 3.

[9] See Robbins, babes and women; Margaret Galvan, Archiving Wimmen: Collectives, Networks, and Comix, in: Australian Feminist Studies 32 (2017), nos. 91-92, pp. 22-40, online https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/08164649.2017.1357007?needAccess=true [08.12.2025].

[10] Priscilla Frank, Meet the Feminist Artist whose crass Comics Were Way ahead of their Time: Aline Kominsky-Crumb Created the first ever Autobiographical Comic made by a Woman, in: Huff Post, 14.02.2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/aline-kominsky-crumb-interview_n_589e1bc8e4b094a129eaff86 [08.12.2025].

[11] Thacker, “Something to Offend Everyone”, p. 13.

[12] Kirtley, A Word to You Feminist Women, p. 275.

[13] Kirtley, A Word to You Feminist Women, p. 274.

[14] Chute, Graphic Women, p. 24.

[15] Cited in Kirtley, A Word to You Feminist Women, p. 274.

[16] Frank, Meet the Feminist Artist.

[17] Kirtley, A Word to You Feminist Women, p. 272.

[18] The Combahee River Collective Statement, 1977, Blackpast.org, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/combahee-river-collective-statement-1977/ [08.12.2025].

[19] Deborah Elizabeth Whaley, Black Women in Sequence: Re-inking Comics, Graphic Novels, and Anime, Washington 2015, p. 20.

[20] Margaret Galvan documents the presence of important (though historically neglected) advocates of lesbianism in the comics community and struggles over sexuality within feminism: Feminism Underground: The Comics Rhetoric of Lee Marrs and Roberta Gregory, in: Women’s Studies Quarterly 43:3/4 (2015), pp. 203-222.

[21] Chute, Graphic Women, p. 24. See Mary Wing, Come Out Comix, Portland 1979, online https://archive.org/details/come-out-comix-1979/mode/2up [08.12.2025].

[22] Galvan, Feminism Underground, p. 203.

[23] Leah Misemer, Hands across the Ocean. A 1970s Network of French and American Women Cartoonists, in: Frederick Luis Aldama (ed.), Comics Studies Here and Now, New York 2018, pp. 191-210.

[24] “Ah! Nana was a French comics magazine published from October 1976 to September 1978, running nine issues. […] It was the first French publication featuring work almost entirely by women […] at a time when comics were still almost exclusively male environments. […] It fully embraced both the culture of the French feminist movement and the American underground scene.” Quoted from: Women in Comics Wiki https://womenincomics.fandom.com/wiki/Ah_!_Nana [08.12.2025].

[25] Misemer, Hands across the Ocean, p. 191.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Misemer, Hands across the Ocean, pp. 192-193. For a discussion of more recent global developments in feminist comics, going beyond the transatlantic world, see: Caroline Kimeu/Constance Malleret/Zeynep Bilginsoy, “Feminism in Pictures: Illustrated Stories of Women’s Rights around the World,” in: Guardian, 05.12.2023, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/dec/05/feminism-in-pictures-illustrated-stories-of-womens-rights-around-the-world [08.12.2025].

[28] Thacker, “Something to Offend Everyone”, p. 15.

[29] For further development of ideas about women comic artists representations of the body, see: Chute, Graphic Women; Galvan, Feminism Underground; and Thacker, “Something to Offend Everyone”.

[30] Olsza’s art-historical analysis of women’s comics suggests several varying schemas that characterized their engagements with the body. Olsza, Towards Feminist Comics Studies, pp. 197-201.

[31] Frank, Meet the Feminist Artist.

[32] Cited in Cynthia Rose, Claire Brétecher (1940-2020), in: The Comics Journal, 14.02.2020, https://www.tcj.com/claire-bretecher-1940-2020/ [08.12.2025].

[33] Michelle Arrow, “It Has Become My Personal Anthem”: “I Am Woman”, Popular Culture and 1970s Feminism*, in: Australian Feminist Studies 22.53 (2007), pp. 213-230, here 214-215.

[34] The place of motherhood in second-wave feminist thought, activism, and comics varied by generation, political context, and individual. For an interesting exploration of the contrasting attitudes around motherhood that developed in the different political contexts of East and West German womens’ movements, see: Katrin Rohnstock (ed.), Stiefschwestern: Was Ost-Frauen und West-Frauen voneinander denken [Stepsisters: What German Women from the East and from the West Think of One Another], Frankfurt a.M. 1994.

[35] One of the early studies of gender roles in women superhero comics is Maryjane Dunne, The Representation of Women in Comic Books, Post WWII through the Radical 60’s, in: McNair Scholars Online Journal 2.1 (2006), pp. 81-91, https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1090&context=mcnair [08.12.2025].

[36] Galvan’s analyses of several women comic artists addresses these complexities, suggesting how comics “visualize and interrogate feminist forms while theorizing new possibilities for women engaging their politics through their bodies. Galvan, Feminism Underground, p. 203.

This article is part of the theme dossier “Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive,” edited by Christina Benninhaus and Mary Jo Maynes.

Theme Dossier: Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive

Zitation

Mary Jo Maynes, Gender Battles in Women’s Comics of the Second-Wave Feminist Era, in: Visual History, 15.12.2025, https://visual-history.de/2025/12/15/maynes-gender-battles-in-womens-comics-of-the-second-wave-feminist-era/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-3000

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Eine Nutzung ist für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in unveränderter Form unter Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de