Book Review: Marwa Al-Sabouni, The Battle for Home

Memoir of a Syrian Architect

Cover: Marwa Al-Sabouni, The Battle for Home: Memoir of a Syrian Architect, London: Thames & Hudson 2017

We have seen our buildings demolished, our cities destroyed and our archaeological treasures vandalized. Those images have been on display so much that we rarely question why all this happened. In politics and history, when narratives are assembled, parties tell their own sides of the story. It is only through architecture that is no one’s particular and everyone’s in general. Buildings do not lie to us: they tell the truth without taking sides. Every little detail in an urban configuration is an honest register of a lived story. (p.10)

With the pictures of bombing, ruins, and death coming from Syria, Marwa Al-Sabouni looks at the role of architecture and planning in the protracted conflict. In a first-hand account from the war-ravaged city of Homs, she tells the story of her native city, illustrated by her own drawings and autobiography. The book consists of six chapters, or six battles, and brings together the role of politics of urban planning, heritage, forced displacement and refugee crisis. The foreword of the book is written by the British philosopher Sir Roger Scruton, followed by a preface to the new edition by the author, and an introduction. The final part of the book includes, in addition to notes and acknowledgement, a historical timeline with the main events in Syria’s modern history, and a discussion guide for a deeper understanding of the Syrian society.

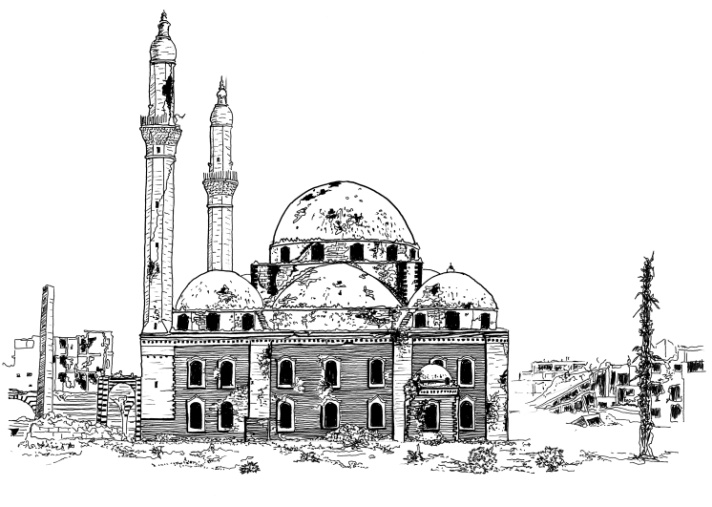

The damaged Mosque of Khalid ibn al-Walid © Courtesy of Marwa Al-Sabouni

Khalid ibn al-Walid Mosque in 2010 © Zeina Elcheikh

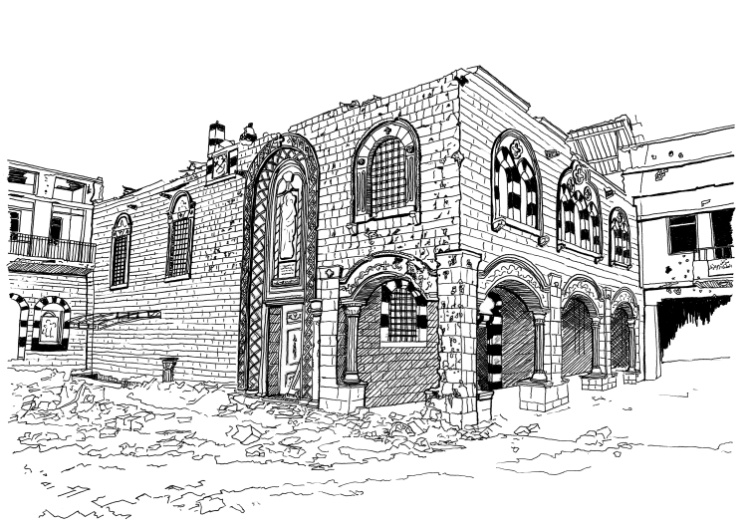

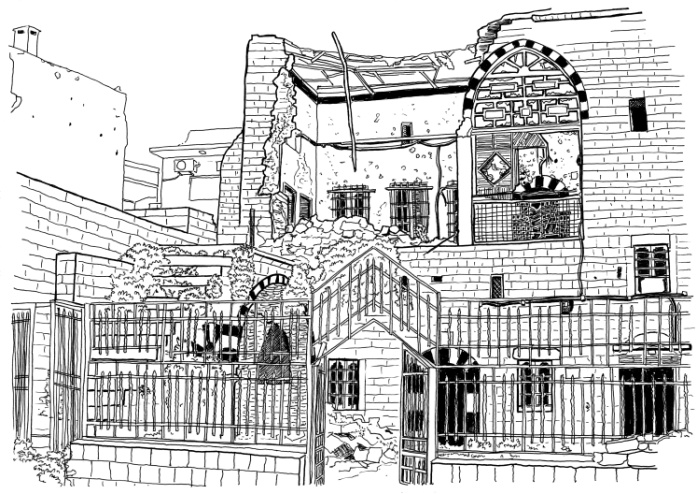

Al-Sabouni offers a unique perspective, through the simple lines of her hand drawings, in which she depicts life in the Old City of Homs, landmarks in Syria, and even protests. Among over 20 hand drawings, sketches and plans, those depicting the damages are the most powerful. The author makes destruction more comprehensible, showing what happened through her own eyes. To draw life in a war zone makes one stop to see, to seek details, and to invest a human touch and a certain amount of time.

Through flashbacks, the author reviews the “series of minor hidden wars” that influenced the actual one (p.13). People living in Syrian cities failed to identify themselves with these shared spaces and looked at their ethnical and religious roots: strengthening what would tear them apart rather than what would bring them together. In Homs, Christians and Muslims lived peacefully with their dwellings and places of worship. The city expanded, afterwards, with newcomers who sought a better life in the prosperous city, but could not integrate easily. They did not accept the established society, and lived in parallel communities. As time went on, urban segregation turned into sectarian conflict.

On the other hand, the educational system did not only harm the architectural profession itself, but also the link between people and built environment. Al-Sabouni studied in her doctoral research, how architecture’s terms and stereotypes in the region became a way of labeling instead of critical understanding. Expressing identity through architecture was criticized and rejected in favor of identity politics. The result was an inability to produce new architecture, and the search for “the lost self” was trapped in a vicious cycle of misunderstanding, misusing and distorting the once great architectural history (p.153).

The author describes the Old City of Homs with its vibrant Souk as a “living museum of ancient architecture” – where goods, services, beliefs and ideas were exchanged for decades. Although there was a building code – at least on paper, the buildings were either left to erode and crumble (eventually to be replaced by new ones), or suffered from poor preservation and restoration. Homs, generally, suffered from manipulation, corruption, and from the temper of its decision-makers. Yet, this cannot be compared with the ordeal under “mortar revenge” and “drops of death” (p. 58), that not only reduced large parts of the city to rubble, but also took many innocent lives.

The damaged Saint Mary Church of the Holy Belt ‘Umm Al-Zinnar’ © Courtesy of Marwa Al-Sabouni

Same view of the Church in 2010 © Zeina Elcheikh

My eyes were taking pictures as I went: snapshots of red faces, empty staring eyes, small drops of cold sweat on tired foreheads. […] You could almost hear their thoughts: has my home been demolished or is it still standing? Is it wiped clean away or are there still a few “memories” remaining? Is it inhabitable, is it safe to walk in, or might it blow up when I enter? (p.52)

The official response to destruction was discriminatory in Syria generally. Affected Christian communities were compensated and provided with new infrastructures, while Sunni Muslim ones were neglected and even banned from returning to their homes (p.109). Baba Amr was among the first cities to revolt in 2011 and was destroyed in 2013. The author believes that this disaster could have been avoided by a fairer urbanization. Therefore, she chose Baba Amr as a case study for the UN-Habitat competition “Urban Revitalization of Mass Housing” in 2013. Her proposal won the first place on the national level. She suggested a “Tree Unit” growing flexibly (p.111-112), inspired by Syria’s old cities with their shade and light effects, their social and climatic considerations.

In the light of the conflict, Homs – with its disorganized urban planning – became a home for war displaced. But, what does home mean? Before the war, owning a home was a never-ending dream. It did not only provide a shelter, but it also granted a social status. For decades, the state failed in meeting the (growing) housing demands. This failure was coupled with a corrupted real estate mafia, rental and services problems. Today with the forced displacement of millions of Syrians, the quest for home took another turn and meaning. Internally displaced found shelters in state school buildings – with their prison-like design and windows covered with wire mesh, or in unfinished concrete blocks. Others left the country to the neighboring countries or to the Western world. Yet, identity crisis and the struggle for belonging cannot be underestimated. Many who left the country did return back.

Al-Zahrawi Palace damaged © Courtesy of Marwa Al-Sabouni

Al-Zahrawi Palace in 2010 © Courtesy of Eng. Manal Odeh, Department of Tourism

Al-Zahrawi Palace in 2010 © Courtesy of Eng. Manal Odeh, Department of Tourism

By and large, The Battle for Home: Memoir of a Syrian Architect is an emotional narrative from a perspective of a Syrian architect and a daughter of Homs, who sees that negligent growth and alleged reformation torn the Syrian cities apart. Decades of urban planning dominated by greed, corruption and discrimination did not only affect the old and new urban fabric of the cities, but it also shattered their social one. Marwa Al-Sabouni shows through her narrative, how urban planning can play a dangerous role. There are, of course, many causes behind the crisis in Syria.

The book is an interesting reading for everyone seeking to know more about the architectural and urban challenges, before and during the war. Today, everyone is speaking about reconstruction in Syria, but what actually needs to be done? Destroyed cities cannot afford home(s) to live in, and the country is faced by a huge challenge beyond its actual means. Yet, there is the chance, in spite of all the suffering, for a new socially engaged approach, otherwise the cities will be exposed to the same old solutions – that were, in fact, problems.

The future of Homs, as Al-Sabouni suggests, depends on a vision of a locally grounded urban planning that match the needs of people, away from corruption and interests. This vision needs be based on the lessons learned from the (recent) past, and not a blind nostalgia longing to the past with all its pitfalls that lead to the tragic present. Cities are not just built environments, but also social fabrics. Homs as any other Syrian city has to offer a shared sense of belonging, beyond the difference of religion and class: if it is to become a “home”.

Marwa Al-Sabouni is an independent practicing architect, and holds a PhD from Al-Baath University in Homs. She is co-founder of the portal “Arabic Gate for Architectural News”, and in 2010 she won the Royal Kuwaiti Award for best media project in the Arab World. Al-Sabouni worked as a lecturer of architectural design in a private university in Hama, and participated in several meetings in Berlin, Beirut, and Geneva about the post-war situations in Syria. She also written for the “RIBA Journal”, “Architectural Review”, “Standpoint” magazine, and “Wall Street International Magazine”. Her TED Talk, in 2016, was selected among the best for the year. In 2017, she spoke at Basel Peace Forum, Bristol Festival of Ideas, the World Economic Forum MENA, the Galway International Arts Festival, and was a keynote speaker at Finland Habitare Expo and at the closing address of Perth Writers Festival. Marwa Al-Sabouni is still living in Homs with her husband and two children. In 2016, “The Guardian” selected her book as one of the best architectural books of the year.

Marwa Al-Sabouni, The Battle for Home: Memoir of a Syrian Architect, London: Thames & Hudson 2017 (Reprint Edition), 192 Pages, illustrated by the Author, 8,33 € (Paperback), ISBN 978-0500292938

Zitation

Zeina Elcheikh, Book Review: Marwa Al-Sabouni, The Battle for Home. Memoir of a Syrian Architect, in: Visual History, 03.12.2018, https://www.visual-history.de/2018/12/03/book-review-marwa-al-sabouni-the-battle-for-home/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-1632

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Copyright (c) 2018 Clio-online e.V. und Autor*in, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online Projekts „Visual-History“ und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber*in vorliegt.

Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <bartlitz@zzf-potsdam.de>