Remembering 10 June

Curating Memory in Lidice and Oradour

The Nazi occupation of large parts of Europe destroyed cities, towns, villages and entire landscapes. Every year on 10 of June, the French village of Oradour-sur-Glane commemorates the massacre that transformed the village into a scenery of ruins. The day has a resonance of death and horror in the Czech village of Lidice alike.

Lidice, 10 June 1942

Among the atrocities committed by the Nazis during the Second World War Lidice remained an unusual case. The non-Jewish Czech village, located 22 kilometers northwest of Prague, was the target after Czech resistance fighters seriously injured Reinhard Heydrich in an assassination attempt on May 27, 1942. “Operation Anthropoid” was the code name for the attack on the high-ranking German SS and police official who served as deputy Reichsprotektor in Bohemia and Moravia. In retaliation for the death of Heydrich on June 4, Lidice was burnt down and razed to the ground on June 10. Only a few ruins remained scattered in the silent landscape: the foundations of a farm, the church of St. Martin and a former local school. The men were immediately shot and the women sent to concentration camps. The children of the village, who were considered capable of being “Germanized”, were sent to German SS families, and the others were murdered.

Postcard showing Lidice before and after the massacre (Zeina Elcheikh).

The massacre and destruction of Lidice was one of the first Nazi atrocities the whole world could know about. The devastation was documented in details, as Jessica Rapson describes: “The Nazis filmed every step of this destruction as a training film – the shootings, the burning of bodies and homes, all evidences of a town burned into oblivion, plowed under. A training film to help others learn to leave no traces behind.”[1] The eradication of the village and most of its inhabitants was a demonstration of the power, control, and supremacy of Nazi Germany. It was a warning. However, the echo of the bloodbath triggered (re)actions and solidarity.

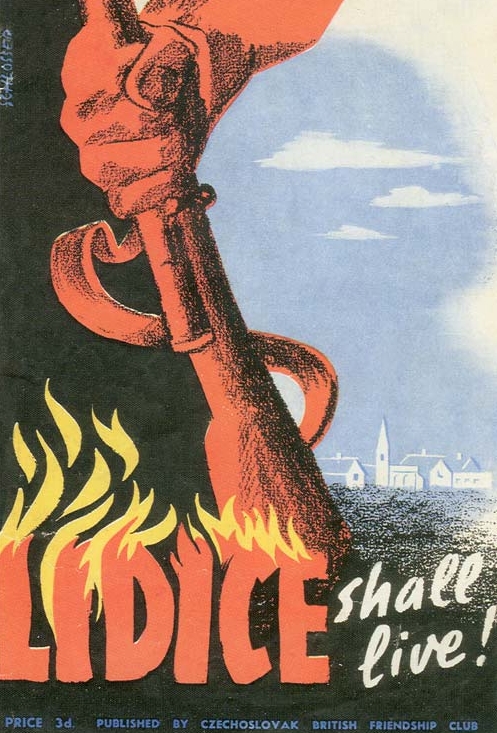

British poster commemorating the village of Lidice. Source: Wikimedia Commons public domain

Immediately after the massacre, news of the devastated village reached a group of miners in Stoke-on-Trent (UK). They sympathized and identified themselves with the people of Lidice: a group of miners like themselves, who lived in a rather modest rural area. The miners of Stoke-on-Trent organized the fundraising campaign “Lidice Shall Live” to facilitate the rebuilding and resettlement of the survivors. Almost immediately after the end of the war a new Lidice was built overlooking the site of the old village.

“The Silent Village” (1943) is a British short film directed by Humphrey Jennings and inspired by the Lidice massacre. The film was shot in a similar mining community as Lidice: the village of Cwmgiedd in Wales. In the same year, 1943, the Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů, wrote his musical work “Memorial to Lidice”.

The first monument to Lidice was erected in 1945. In the early 1950s the first museum was opened. On the 20th anniversary of the massacre in 1962, a new museum was built following the design of the architect František Marek. The exhibition tells the fate of the village and its residents. A rose garden was created by the group of “Lidice Shall Live”, and was established as a garden of peace and friendship.[2] In the late 1960s, the Czech sculptor Marie Uchytilová, initiated the “Memorial to the Children of Lidice”. By depicting the 82 children of the village (42 girls and 40 boys), she wanted to pay tribute to the young victims of the war. Uchytilová died in 1989, leaving her work unfinished. In the 1990s, donations were organized to continue what she had started. The first statues were installed in Lidice in 1995, and the last one on 10 June 2000.

Memorial to the children of Lidice overlooking the site of the massacre. Photo: Dezidor,

Čeština: Lidice 2011. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Licence: Dezidor CC BY 3.0

The Lidice massacre is remembered in several places and in various forms. Towns, neighborhoods, buildings and streets were renamed “Lidice” in several countries. Memorials were built as well in Wisconsin (U.S.A) and in the Wallanlagen Park in Bremen (Germany). In 2017, 75 years have passed since the tragedy. On this occasion the English composer Vic Carnall wrote his Opus 17 “In Memoriam: the Village of Lidice”.

Oradour-sur-Glane, 10 June 1944

Saturdays were often busy in Oradour, a small village in the department of Haute-Vienne in west-central France. June 10, 1944 seemed to be no exception: shopping for food and grocery, going to the barbershop, and chatting with the neighbors. A medical check was even scheduled for the afternoon at the local school. However, by midday, the way life used to be in Oradour-sur-Glane would change forever.

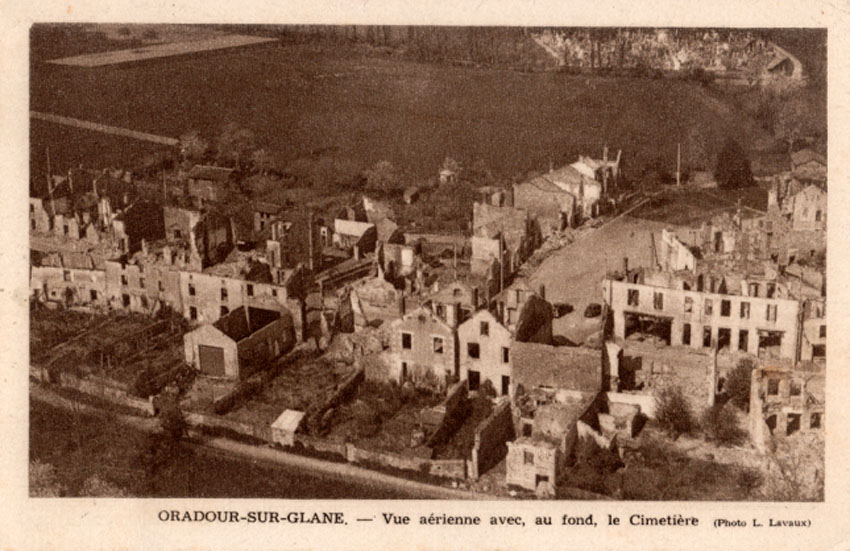

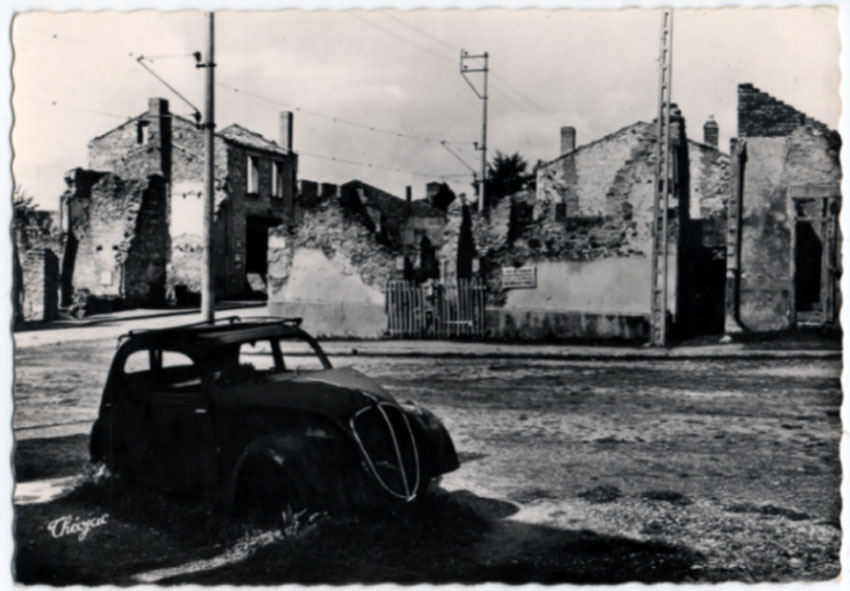

The 2nd SS-Panzer Division “Das Reich” reached the village at noon, and 150 soldiers blocked the entrance to the village. The curtain of time was drawn over Oradour, and an act of atrocity began. On the next morning, one could still see smoldering houses, farms and shops. Oradour-sur-Glane was reduced to blackened stones, charred remains and ashes. Among the Nazi crimes, the massacre of 642 women, children and men of Oradour on 10 June 1944 was one of the most notorious.

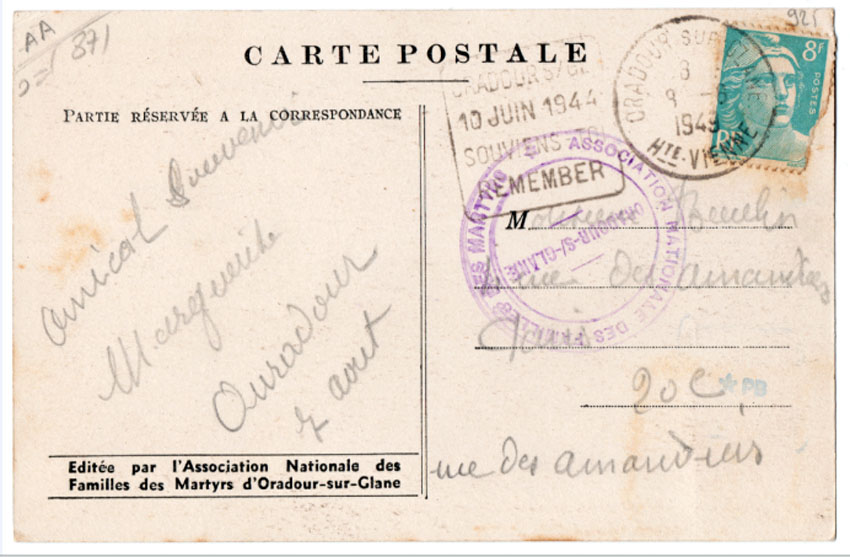

Postcard from August 1949 (Zeina Elcheikh). Among the stamps, one reads “Oradour S/GL, 10 Juin 1944, souviens-toi, Remember”. A commemorative sign with the inscription “souviens-toi, remember” is located at the entrance of Oradour.

In 1945, there was a need for a symbol for a resistant France, which had been partially destroyed by the barbarity of the Nazis. After the visit of General Charles de Gaulle to the ruins in 1945, a special legislation was passed in 1946 designating the village as a historic monument. The way the ruins have been preserved is a model for “ultimate victimization”, as Sarah Farmer argues: “a peaceful French town, uninvolved in any resistance activity, destroyed and murdered its inhabitants.”[3] Without involving the few survivors in the decision to turn the site into a memorial, Oradour-sur-Glane became the martyr village of France: a sacred place belonging to the French nation.

Postcard showing Oradour after the massacre (Zeina Elcheikh).

In 1947 Pablo Picasso painted “L’enfant d’Oradour”. It was most likely the portrait of Roger Godfrin, the only child (almost 8 years old) who survived the massacre. In 1984, the English writer David Hughes wrote his novel “The Pork Butcher”, based on the massacre of Oradour-sur-Glane. The novel was filmed in 1989 under the title “Souvenir”, directed by Geoffrey Reeve. In 1999, the French President Jacques Chirac inaugurated the “Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour”: a memorial museum located near the entrance to the ruined village. The museum hosts personal items of the victims, which were recovered from the ruins. In September 2013, German President Joachim Gauck and French President François Hollande visited the ruins of Oradour-sur-Glane. It was the first time that a German politician had been on the site of one of the infamous massacres committed by the Nazis in France during the Second World War.

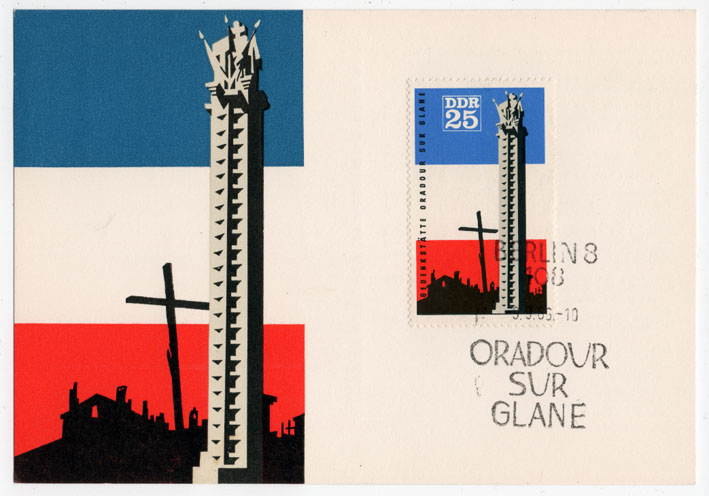

Postal stamp from the GDR commemorating Oradour-sur-Glane, showing the monument to the 642 victims of the massacre.

Concluding Thoughts

June 10 is a day of commemoration in memory of the massacres of Lidice and Oradour-sur-Glane. The people in both villages suffered from the terrible atrocities committed by the Nazis. Whereas the perpetrators were determined to document and propagate the annihilation of Lidice, they tried to limit the public discussion about the massacre in the French village. In Lidice and Oradour, new villages were built to relocate the survivors.

Physical remains can evoke an understanding of the past and its history. Absence and silence can do the same. The ruins in Oradour are an authentic part of the commemorative landscape. On the other hand, the lack of physical remains in Lidice – except for a few visible foundations – led to other alternatives of remembrance in the silent scenery. Between moving on and looking back, 10 June in Lidice and Oradour-sur-Glane will keep curating memory in absence and ruins.

People walking through the landscape where Lidice once stood. Photo: PeterBraun74, Lidice Memorial, 23 June 2018. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0

Preserving the ruins of Oradour led to the freezing of time in the remains of the village. With the time passing, weathering washed away the blackened stones and vegetation spread through the ruins. Photo: Gvdbor, Oktober 2004. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Licence: CC BY-SA 3.0

[1] Jessica Raspon, Topographies of Suffering: Buchenwald, Babi Yar, Lidice, New York 2015, 153-154.

[2] Raspon, Topographies of Suffering, 143.

[3] See Sarah Farmer, Martyred Village: Commemorating the 1944 Massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane, Berkeley 1999.

Zitation

Zeina Elcheikh, Remembering 10 June. Curating Memory in Lidice und Oradour, in: Visual History, 09.06.2020, https://visual-history.de/2020/06/09/remembering-10-june/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-1776

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Copyright (c) 2020 Clio-online e.V. und Autor*in, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online Projekts „Visual-History“ und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber*in vorliegt.

Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <bartlitz@zzf-potsdam.de>