In Search of the Drowned: Testimonies and Testimonial Fragments of the Holocaust

An interdisciplinary digital monograph

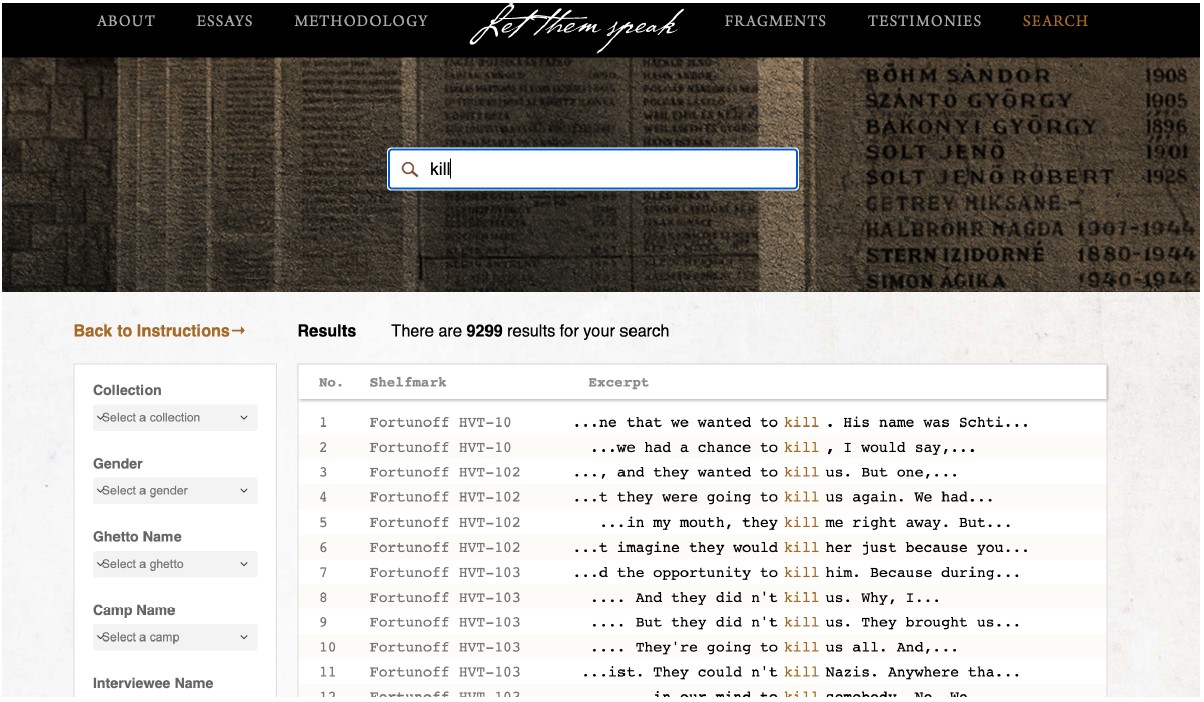

Screenshot of the homepage. The website “Let them speak” is the epigraph of the digital monograph, Gabor Toth ©

During the Holocaust 5.8 million people were killed; most of the victims did not leave behind any record that could help reconstruct their experience. While survivor history has been well studied in the last decades, how millions of voiceless victims experienced their persecutions has remained a terra incognita. Generally, while perpetrator history is well-documented, the voiceless victims’ perspective has resisted any form of documentation; their emotional and mental experiences conveyed through novels and memoirs have remained fragmented and they have often been dismissed as subjective and unreliable. Today Digital History and Digital Humanities offer new forms of inquiry and representations; they can unlock the emotional, mental, and physical realities which voiceless victims of the Holocaust or other genocides were forced to live in.

To address the experience of the Voiceless, this interdisciplinary digital publication brings together theoretical considerations underlying Genocide and Holocaust Studies with new practices of digital scholarship. Precisely, it elaborates and features a new digital representation that symbolically gives voice to the voiceless victim.

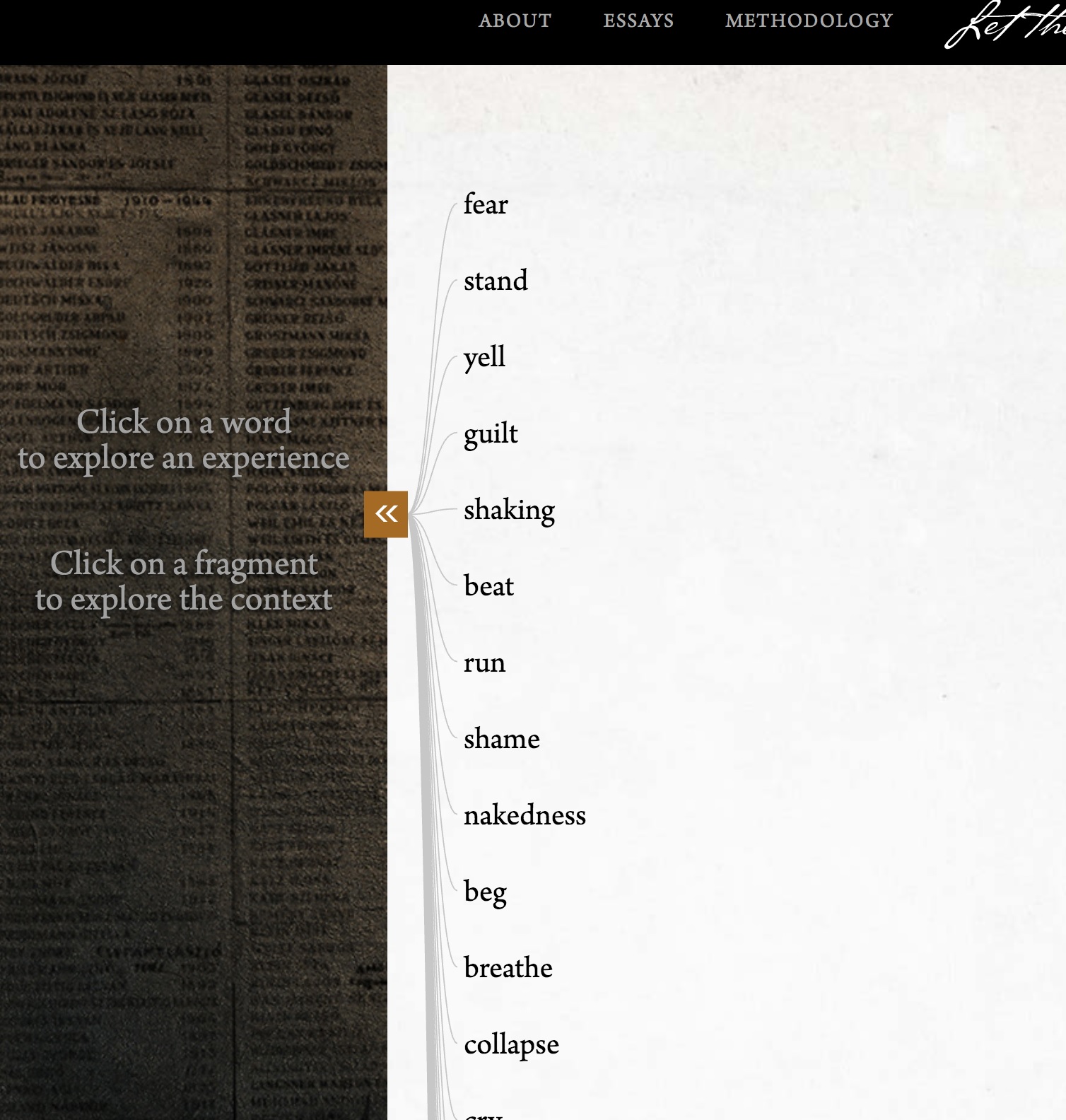

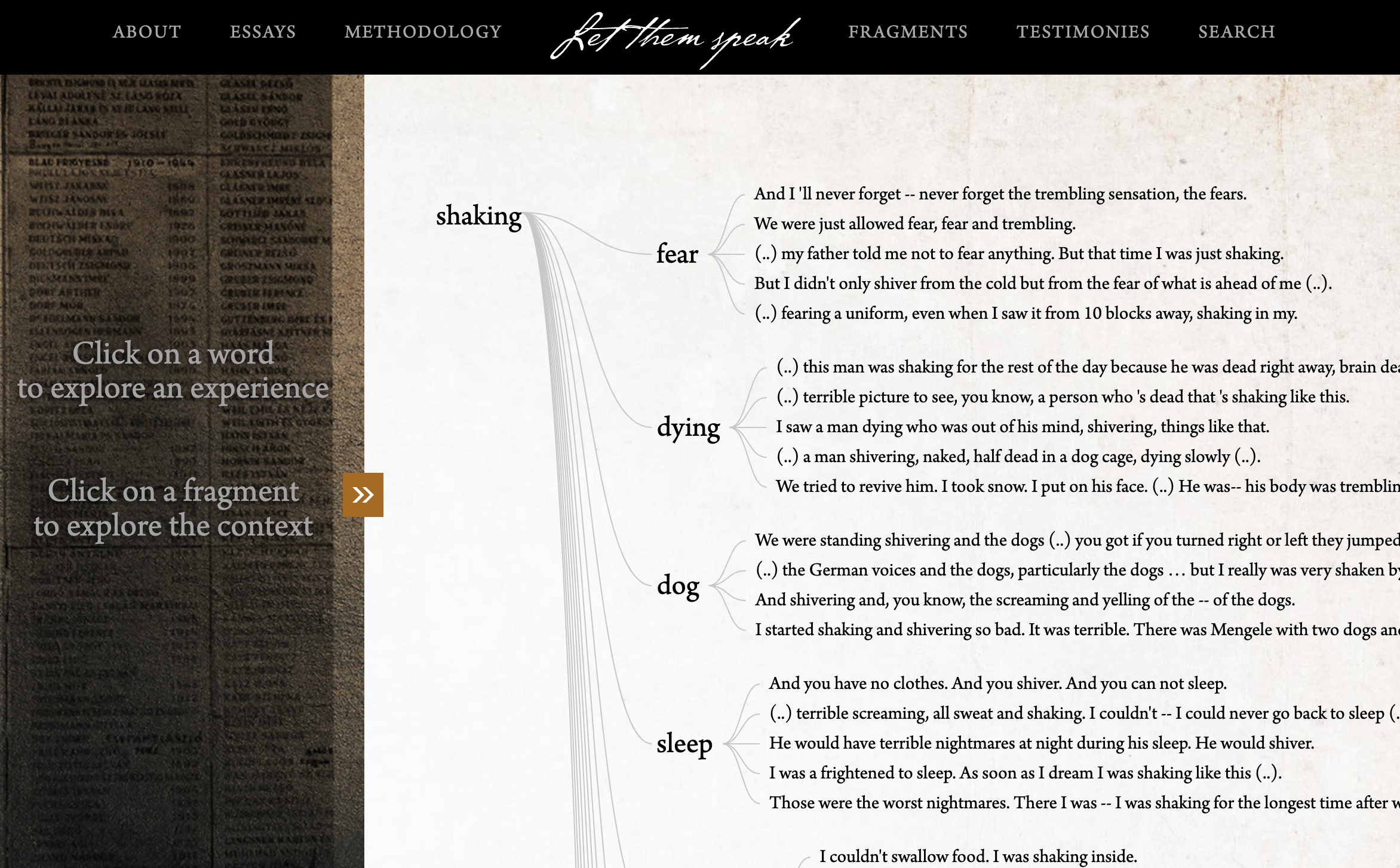

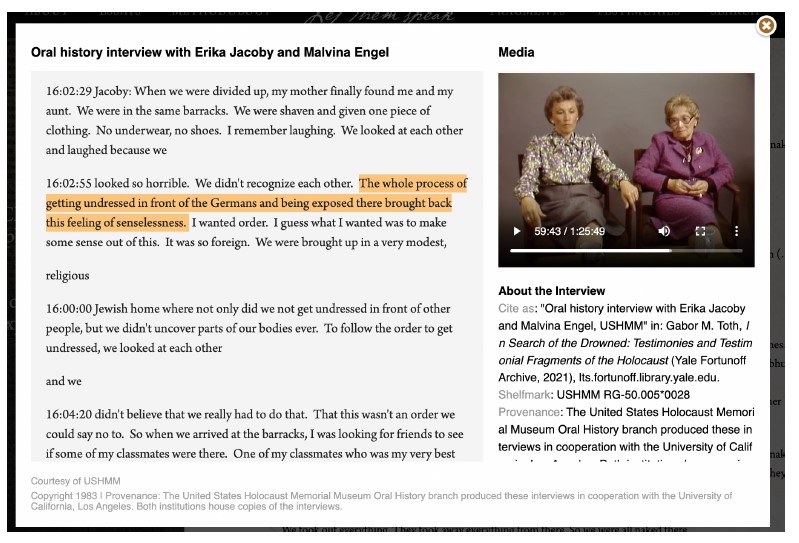

The new digital representation that this publication features is an inventory presenting some aspects of the collective experience of persecutions. The inventory is the visualization of those mental, emotional and physical experiences that any victim, including the Voiceless, must have gone through (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). In practice, the digital inventory presents certain episodes of persecutions that are recurrent in 2700 English language survivor testimony of three collections: Yale Fortunoff Archive, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive. Elements of the inventory, that I name testimonial fragments, have been retrieved by means of data mining techniques and visualized with the help of a hierarchical tree. Since the experiences that the inventory features are directly connected with complete and unabridged testimony transcripts, readers can also study and read these experiences in their original context. On the one hand, the digital inventory memorises the Voiceless by presenting the possible episodes of persecutions she or he must have faced. On the other hand, it opens reading paths along the mental, physical and emotional experiences of persecutions in thousands of testimonies (Figure 3). The digital inventory is an innovative exploratory tool that presents various aspects of persecutions from victims’ perspective.

Figure 1, An inventory, a hierarchical tree visualization, presenting mental, physical, and emotional experiences that any Holocaust victim was likely to face, Gabor Toth ©

Figure 2, Testimonial fragments, the leaves of the hierarchical tree visualization, document victims’ experiences as possibilities, Gabor Toth ©

From a scholarly point of view, the inventory draws on two key arguments developed throughout a collection of essays that this publication features. First, through the collective experience of persecutions, it is possible to reconstruct a mosaic of possible physical, emotional, and mental episodes that murdered victims must have gone through. Second, the collective experience of persecutions can be recovered from thousands of survivor testimonies. Some Holocaust scholars such as Lorenz Langer and Christopher Browning have come to similar conclusion. For instance, Browning has proposed the concept of individual plural to describe the collective nature of Holocaust testimonies. However, the problem of how to extract the collective experience from historical sources such as thousands of survivor testimonies of genocides remains an important challenge for Digital Humanities and Digital History. It is equally unclear how a mosaic gathering some pieces of the collective experience related to a historical event can be represented as a tangible historical source. Digital History lacks practices to develop representations of the collective experience that researchers, educators, students, and the general public can use to approach the traumas of the past. In short, collective experience has been discussed in the context of both the Voiceless and the testimonies of Holocaust survivors; nonetheless, it has remained a challenging concept for digital approaches to mass events of the past.

This book tackles the challenge of giving symbolic voice to the voiceless through the digital representation of victims’ collective experience in three different sections.

The first section is the digital edition of the 2700 English language testimonies from three major US collections. This section contains the digital inventory described above and offers tools to browse, read, watch or search in entire testimonies (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). The digital edition section also makes testimony transcripts searchable as a linguistic corpus, which opens new research directions for Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

Figure 3, Readers can read and listen testimonial fragments in context; they can thus explore subjective experiences featuring victims ‘ perspective, Gabor Toth ©

Figure 4, A sophisticated corpus engine help readers navigate in thousands of testimonies, Gabor Toth ©

The second section is a collection of scholarly essays that develops the theoretical and methodological underpinning of the digital representation rendering the experience of the voiceless. It focuses on three scholarly themes (experience of murdered victims, recovery of collective experience from testimonies, representation of the collective experience) in three respective parts followed by an epilogue and preceded by a prologue. Most importantly, it situates the book’s two arguments in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and connects them with practices of Digital Humanities and Digital History. In addition to the discussion of scholarly ideas, the collection of essays also involves the ideas and experience of survivors; yet some of its arguments are developed by reflecting on leitmotifs in testimonies. Each scholarly essay is preceded by a short prologue where I connect the topics of the essay with my own personal memory of the Shoah. This continues the tradition by previous scholars (for instance, Ivan Jablonka, The History of Grandparents I never had,Stanford: 2012) who also embedded their own memory.

The third section explains the digital methodology used as part of this project and gives a detailed description of the 2700 testimonies.

The significance of this publication is twofold. Until our days survivors could keep up a living memory of the murdered victims. Following the death of last survivors, it is an open question who and how will carry the memory of the Voiceless. There are approximately 100.000 Holocaust testimonies dispersed in the archives of the world. It has often been assumed that the Voiceless is implicitly present in these testimonies. In the words of Geoffrey Hartmann, a Holocaust survivor and scholar, as well as one of the founders of the Yale Fortunoff Archive, in their testimonies survivors “speak for the dead and in the name of the dead.” Today, with the imminent death of last survivors, it is crucial to reflect on how the implicit presence of the dead in thousands of testimonies can be made explicit to next generations. This is an important challenge for historians, archivists, and curators.

In the last three decades, many Holocaust historians, such as for instance Marion Kaplan, Alexandra Garbarini, Laura Jockusch, Amos Goldberg, and Tim Kohle, have investigated the mental and emotional experience of persecutions. Their works mainly focused on diaries and letters of murdered victims. Despite the increasing interest, the study of the affective and mental dimension of persecutions through large testimony collections has been challenging. Emotional experiences of victims are dispersed in tens of thousands of testimonies. Neither archivists nor historians have methods to retrieve, catalogue, and represent emotional and mental experiences. In a recent collection of essays (Probing the Ethics of Holocaust Culture ed. by Wulf Kansteiner, Claudio Fogu, and Todd Pressner, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), both the Holocaust historian, Todd Pressner, and the CEO of the Shoah Foundation, Stephen Smith, have pinpointed this difficulty. In the words of Pressner, it is “challenging to mark-up emotion in a set of tables.” A digital representation of victims’ emotional and mental experiences embedded in both theoretical problems of Holocaust and Genocide Studies and in the practice of Digital Humanities and Digital History will support the work of Holocaust historians, as well as students of Genocide Studies.