Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive

Introduction

Putting Images to Work: Constructing, Complicating and Subverting Gender

As cultural products, images are infused with notions of gender – notions, which are, of course, specific to the times and places in which these images originate. For gender historians, they are fascinating artefacts, but often also frustratingly difficult to interpret. This dossier presents the work of historians who look at gender through visual sources. The contributors engage with a wide variety of visual sources (including book illustrations, posters, photographs, and comics) to explore gender history in a range of places and moments in time. Our aim is to examine how historical actors have used images as they negotiate gender, and how we as historians can incorporate these images into our analyses of gender history. Not surprisingly we have discovered that working with images as historians is complicated – even more complicated than working with more conventional text-based sources – but that it is also fascinating and fun. So, we still want to do it!

We began our group conversation about studying gender through the visual archive at the 2023 Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, Genders, and Sexualities.[1] We believe that visual sources can bring to light, illustrate, make visible, document, and help us to see dimensions of the past which are only hinted at in text sources, or are even rendered invisible. (All puns intended!) Visual sources can open up new perspectives on the past that have been relatively absent from mainstream archives. However, we are particularly intrigued by their openness to interpretation and by their effects on the viewer. As we work with images, they work on us. They point to contradictions and uncertainties in cultural perceptions of gender, to the longevity of traditions and to the ways in which gender is inscribed into bodies, practices, institutions and the material world.

Historians have often used images illustratively. Along with other historians publishing in visual-history.de, we want to approach them more analytically. We explore why, by whom and to what purpose images were employed, how they were produced and circulated, how they were perceived. (Even if the latter question is particularly tricky to answer.) Images often allow for a variety of interpretations, and they can appeal to contemporary and later viewers on an aesthetic and emotional level. They might not always provide answers to historical questions, but they certainly offer food for thought.

Power structures are engrained in all archives, including the visual one. If we conceive of the visual archive as a hybrid collection held in many different places, including people’s minds, we can easily see that the possibilities of seeing, let alone making images were unevenly distributed. Patrons, dealers and experts decided on what was commissioned, bought, collected and exhibited in private and public spaces. Art education was often a privilege. It took time for photography and filmmaking to become available to most. And while having one’s likeness taken could be a pleasurable experience and a source of self-fulfilment, others sold their looks or were not asked for consent when their image was taken.

While the visual archive thus contains traces of lives and perspectives not recorded in other sources, it needs to be treated with suspicion and caution. Already in the 1970s, feminist art historians and media scholars like Linda Nochlin, Griselda Pollock and Laura Mulvey started to ask critical questions: How are women and gender relations represented in art? Who gets to produce images and whose gaze is inscribed in them? Whose work is included in the visual archive and on what terms? Whose experiences are worthy of representation and whose are excluded or can only be reconstructed through the distorting male, racist, colonial or medical gaze of the more powerful? Whose standing is enhanced, whose subjugation and exploitation justified? Who is offered possibilities of identification and pleasure by ways of consuming images?

Nevertheless, for all this selectivity and despite deeply ingrained power relations, we suggest visual sources can cast new light on otherwise shadowy histories. Almost inevitably, they raise questions of agency as they are being produced, reproduced, circulated, sold and bought, viewed, interpreted, exhibited, destroyed, preserved, collected, and remembered. Regarding gender history in its intersection with histories of racism and other forms of subjugation, dominance and violence, a single image can document both – the violence used to oppress and exploit and the agency and humanity of the subjugated.[2] Images – from drawings and etchings to photographs and films – have been used to document the most terrible atrocities and violations. They have also been used to persuade their viewers to accept hierarchies and inequalities. Images often emerge out of moments of negotiation: They reflect attempts by painters or photographers but also by sitters to produce meaning. They document the desire to represent a certain historical situation, to tell a story or to offer an interpretation, but they also show that such attempts often fail because audiences (and critics) see otherwise. It is this multiplicity of meanings and readings which make visual sources so intriguing and valuable.[3]

Works of art dating back to cave paintings, millennial-old religious iconography, and ancient medical illustrations have contributed to the construction, circulation, and normalisation of notions of gender since the beginning of recorded human history. As forms and technologies of visual representations have evolved across time, they have depicted gendered bodies and gendered practices and beliefs in ways that have taught and reinforced hegemonic notions. Women’s and gender historians as well as feminist art critics have therefore always been interested in analysing and deconstructing such visual discourses.[4] But images can also act as powerful tools for questioning, complicating, and undermining prevailing notions of gender as testified e.g. by graphic novels and exhibitions of feminist art which have become so much more common over the last decade or two. In this dossier we are particularly interested in exploring the complexities faced by both historical actors and historians. We examine how images have been “put to work” in the past – that is, used and experienced by historical actors. And we are also interested in demonstrating how surviving visual sources can be “put to work” by historians doing gender history.

Five Examples of Studying Gender through Visual Materials

This dossier starts off with five papers which look at visual sources from different historical moments and places. Other papers might be included later. Each of these first five papers asks how images were used to represent and negotiate notions of gender. While different in technique and style, the images interpreted here all represent human figures which can be easily read as belonging to specific categories of gender, class, age group, race, occupation etc. And all the images we study are accompanied by and interact with texts. They were usually published or otherwise circulated at the time of their production and were always viewed by larger audiences. Hence, they can be seen as interventions in broader discourses. They are – not necessarily at first sight – political.

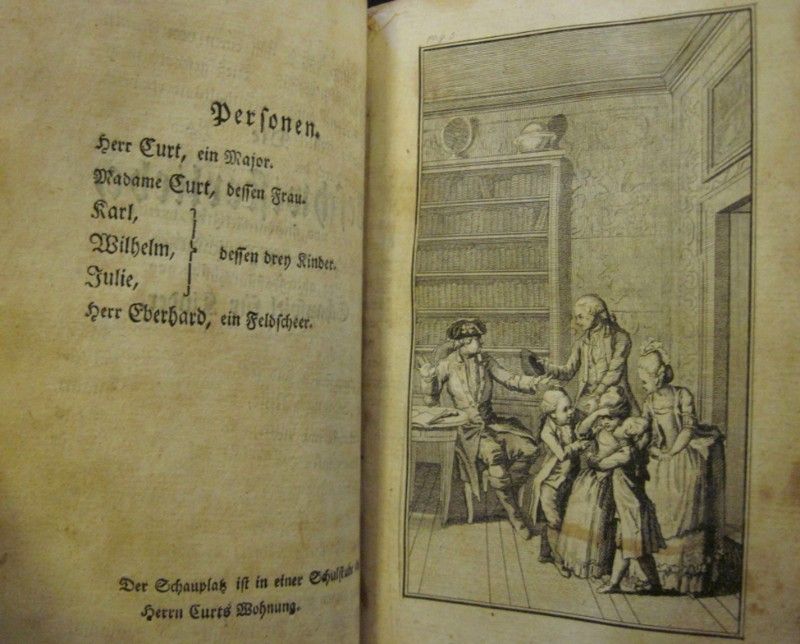

This dossier starts with an essay by Emily Bruce entitled “Ambiguous Representations of Gender in Late-Eighteenth and Early-Nineteenth Century Illustrations in German Children’s Literature.” Bruce focuses on some of the earliest publications for children in Central Europe – storybooks, textbooks, and periodicals. These works established conventions and norms that powerfully shaped the subsequent evolution of children’s literature. As Bruce shows, the values they conveyed were not only carried by words. As printing technologies advanced around 1800, illustrations were used to reach out to young readers (and their relatives). The authors were inspired by bourgeois values centring the private sphere and new pedagogical ideals promoting creative forms of learning. However, these did not necessarily align easily with the perceived notions of gender binaries that were also important for the bourgeois project. As a result, Bruce argues, the ways early picture books and periodicals taught gender were messy and sometimes surprising.

As contemporary readers and female historians, we find some of the images very relatable. Which feminist scholar wouldn’t enjoy an image of girls depicted as readers and learners? And who wouldn’t be intrigued by the loveliness and tenderness of the children clinging to their siblings and parents? However, the images might also be read as pointing to the darker sides of bourgeois gender and adult-child relations: the depictions of girls so very well-behaved, nicely clad, slim and clean, so obedient and docile, forgiving and accommodating, especially when it comes to silently licensing and enduring the misbehaviour of boys, point to a pedagogical agenda, which told girls and boys from an early age that not all people were created equal and that, for men, the pursuit of happiness included the domination of others, especially women. Even though the reception of these images is difficult to study, their analysis shows that they invited their child readers to identify with the children depicted. The images thus point to the energy and ingenuity it took to inculcate bourgeois gender ideology in children.

Cast list and facing illustration of “Sibling Love” (Weiße, 1776). Source: Staatsbibliothek Berlin

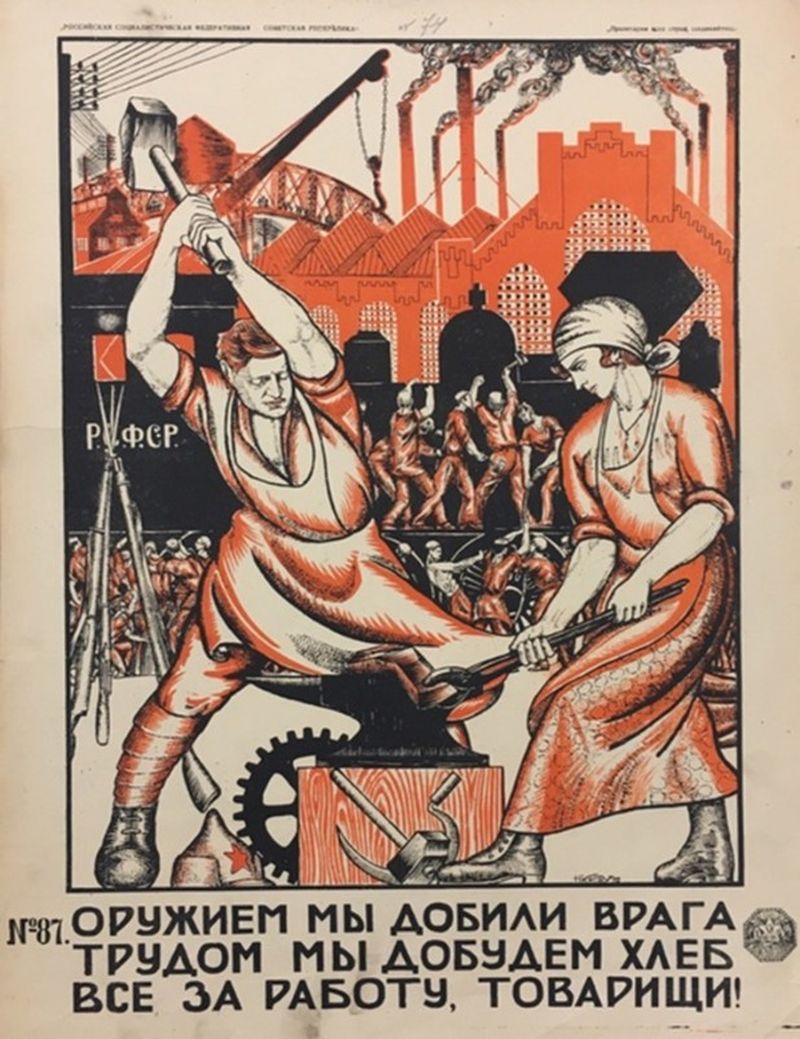

In the next essay, “Gendered Bodies on Soviet Posters, 1917-1924: The Visual Representation of Backwardness,” Elizabeth Wood works with images of a very different sort. Wood begins by observing that images are often thought to merely “illustrate” other forms of didactic or political messages, to play a secondary role. Here, however, she addresses the question of what happens when visual images and the written words contradict or even undercut each other. Her focus is on posters produced during the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent Civil War. The new rulers relied heavily on visual imagery, especially posters, to convey their political messages. Her analysis of the posters reveals a gendered dichotomy between the portrayals of the new Soviet man and the portrayals of the new Soviet woman. Male bodies were portrayed as active and forward-looking. Female bodies, by contrast, were associated with forms of “backwardness” that the state needed to remedy. A new iconography of forward-looking men and backward-looking women helped to set the tone for a new gender order that, while egalitarian in official ideology, was not always so emancipatory in its visual representations and practices.

Nikolai Kogout, “With our weapons we defeated the enemy. With our labor we shall have bread.

Everyone to work, comrades!” (Oruzhiem my dobili vraga. Trudom my dobudem khleb. Vse za

rabotu, tovarishchi!) Moscow,1920, Source: Soviet Political Poster. The Sergo Grigorian Collection,

http://redavantgarde.com/collection/show-collection/945-our-weapons-defeated-the-enemy-our-labour-made-the-bread-everyone-to-work-comrades-.html [02.10.2025]

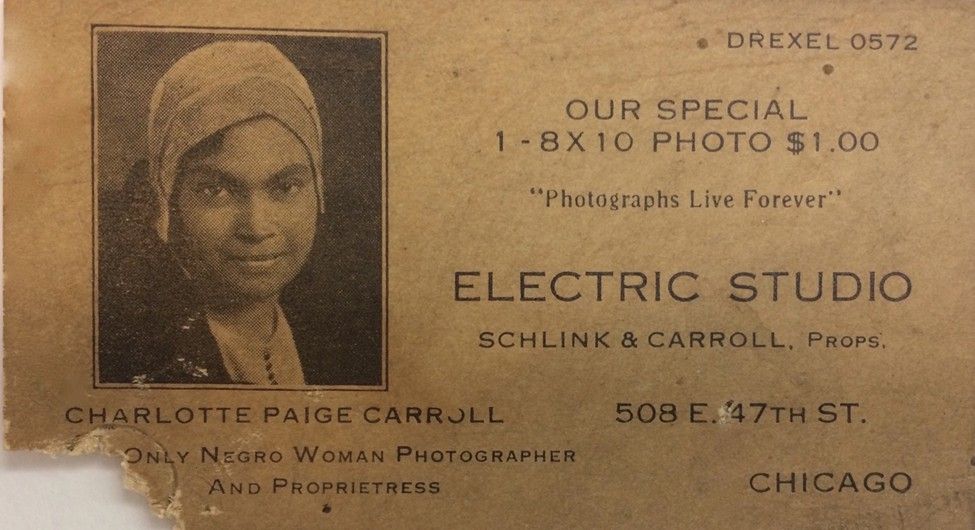

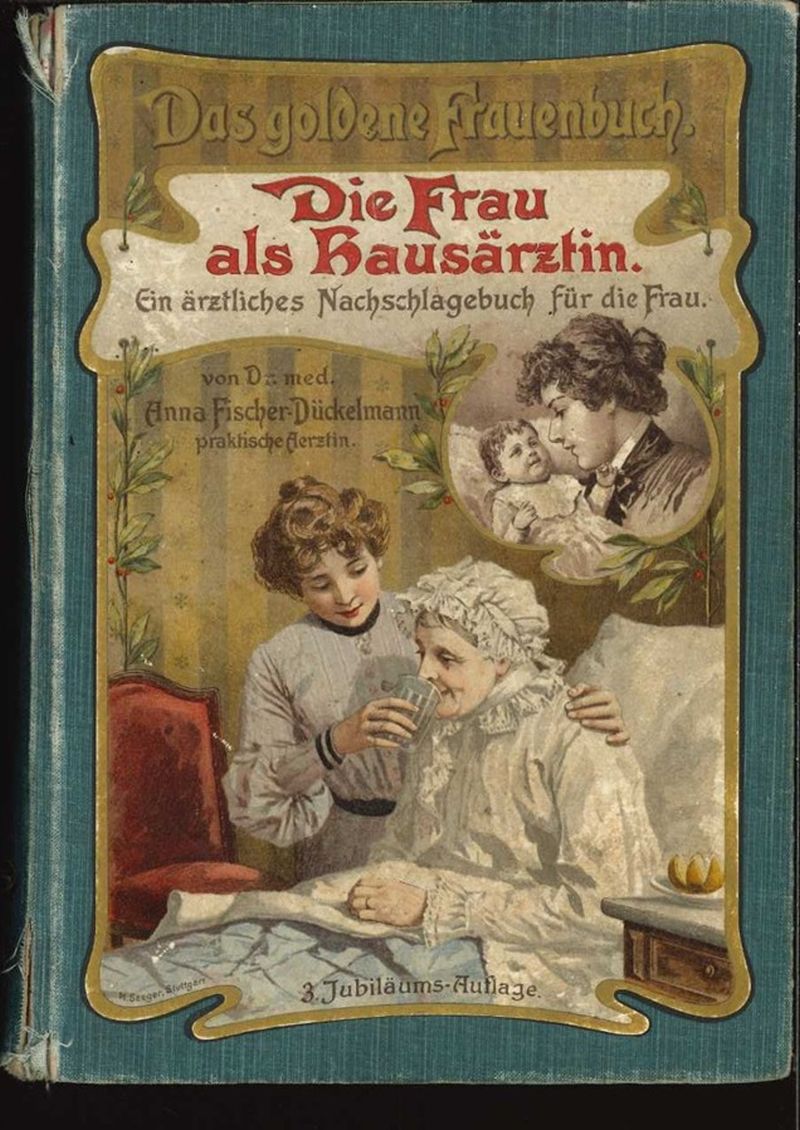

Business Card of Charlotte Paige Carroll of Electric Studio, Chicago, c. 1930, Source: Louis “Scotty” Piper Collection, Chicago History Museum

In her essay, “Celebrating female agency: Illustrations in early 20th century medical advice books for women,” Christina Benninghaus focuses on the immensely popular medical handbook “Die Frau als Hausärztin” by Anna Fischer-Dückelmann. It was lavishly illustrated, boasting hundreds of images taken from diverse contexts or specifically produced for this publication. They encouraged their readers to inspect bodies (their own and those of family members), to imagine biological processes and human anatomy, to avoid pregnancies, and to administer treatments. In doing so, they visually constructed an imagined female reader who was resolute, competent, intellectually curious and knowledgeable. Sidelining questions of gender relations by showing women in a private environment almost completely devoid of men, the images, Benninghaus argues, carried a political message easily lost on today’s viewers. At a time when women were only about to gain access to medical education and when almost all women had to rely on male doctors, these illustrations envisaged an alternative reality in which women had already gained the knowledge and status male doctors were trying to keep from them.

Title page of Fischer-Dückelmann’s bestselling book “Die Frau als Hausärztin”

(The woman as family physician; English translation published under the misleading

title “The wife as family physician”) first published in 1901 (Stuttgart).

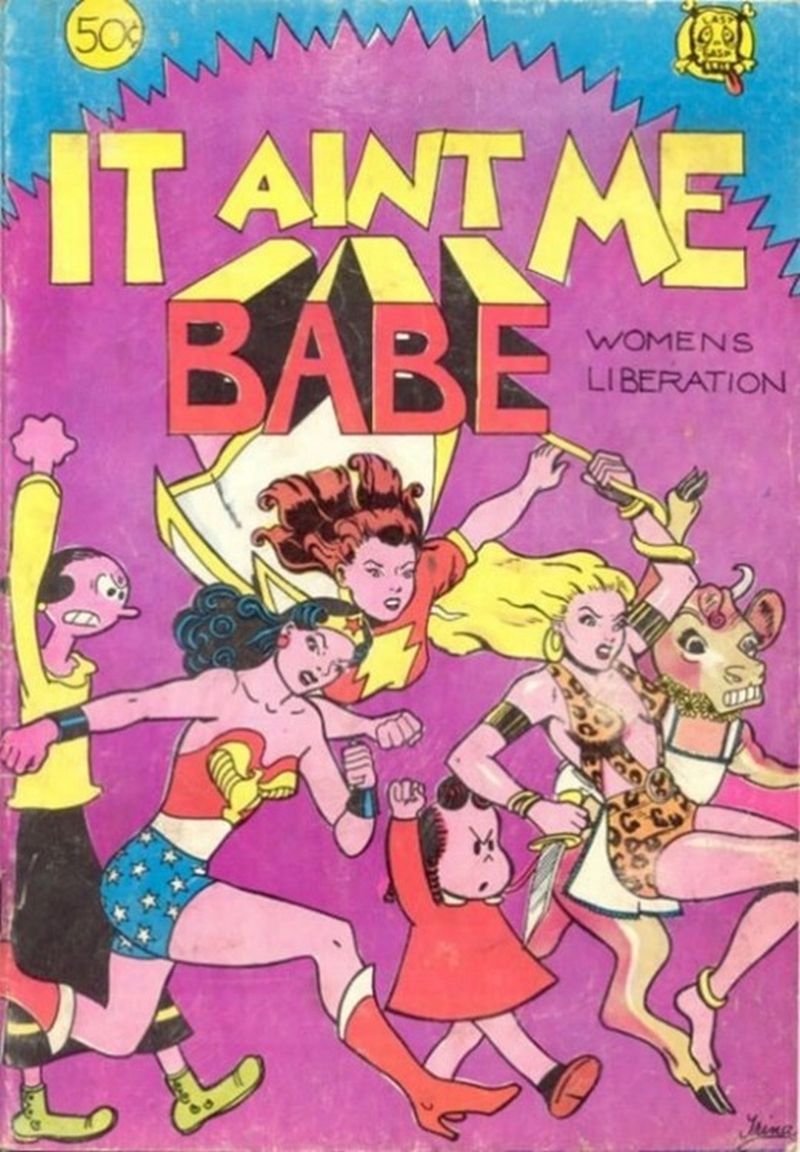

Finally, the last essay in the dossier turns to a very different visual form – comics – to analyse gender history. In her essay, “Gender Battles in Women’s Comics of the Second-Wave Feminist Era,” Mary Jo Maynes focuses on women in the U.S. and Europe who, beginning around 1970, turned to the comic form to contest gender inequities, even as more widely recognized feminists took on patriarchal relations in writing. As Maynes points out, Feminist literary and art critics have been alert to the significance of women’s comics of this era, but these works have less often been taken up by historians of women, gender, and sexuality. This essay, drawing primarily on examples from the U.S. and France, explores how these particular visual sources bring new perspectives to historians’ understanding of the history of second-wave feminism and its legacies.

Trina, It Aint Me Babe. July 1970, cover ©. Republished in “The Complete

Wimmen’s Comix”, Vol. 1, Fantagraphics Books, 2016, 1 ©

Ambiguities

Several of the essays explore images that might be seen as reinforcing gender norms consistent with the ideals and practices of already powerful or emergent social and political forces. For example, Bruce and Benninghaus concentrate on images visualising domestic life, which was so important for the self-perception and self-representation of the modern bourgeoisie in Central Europe. Bruce highlights the increasingly important role of illustrations in German children’s literature in the socialization of children in bourgeois households and in schools – illustrations that could serve as “instrument[s] for eliciting and managing the child reader’s affective response.” In the images analysed by Benninghaus, this domestic space is represented as a realm suitable for the professional work of the female physician and the educated medical self-help and care provided by housewives and mothers. In a very different case, Wood looks at political posters as visual tools employed by the early twentieth-century Soviet regime to promote gender norms consistent with its revolutionary aims.

However, even while noting how images can work to promote culturally hegemonic or official views about gender, these essays also suggest that images and their meanings are far more difficult to control than texts. They can be ambiguous and contradictory in themselves or at least allow a variety of readings. This, after all, is one of the main reasons why images often come with captions. For example, Bruce notes that one of the periodicals she studied – The Children’s Friend – at times included illustrations of girls in surprising, counter-hegemonic situations. Therefore, she argues, we “see a mosaic of both emancipatory and essentialist notions about girls’ place in the world” in these illustrations. The notion of a mosaic can certainly also be used to characterise the enormously heterogeneous nature of the images included in the books studied by Benninghaus. They ranged from homely scenes to images directly taken from medical literature which would have been out of reach for many female readers. Who is to say which images appealed to whom and which messages readers took away from them? As Wood points out, even the Soviet posters are far more contradictory than one might expect. Emphasizing visual dimensions such as placement and stance of male and female figures represented, Woods notes that “the contrast with Bolshevik propaganda in written texts is stark. While official Bolshevik PR emphasized women’s equality and their new roles in industrial production, these visual works tended to place women in classic spheres of backwardness.”

When thinking about such contradictions and ambiguities, it is worth considering the technical processes necessary for producing and reproducing images. Publishers could lower costs by reproducing already existing images. And those artists, engravers and lithographers capable of producing new images brought their perhaps long-acquired skills, their ideas about visual conventions and their (sometimes limited) creativity to the table. Illustrated books, newspapers, journals and propaganda campaigns need to be seen as emerging out of collaborative processes which – while difficult or often impossible to reconstruct – should not be imagined as straightforward.

Some of the images examined in this dossier were deliberately intended to question or subvert dominant gender norms. As Maynes points out, comics by women artists pushed back against inegalitarian gender norms: “Women artists increasingly deployed the comic form to criticize the sexism that was all too often expressed graphically in the very comics that were so much a part of the 1960s youth cultural rebellion.” The political messages engrained in the images of women doctors represented in Fischer-Dückelmann’s bestselling health book are perhaps more difficult to discern. However, the book was published at a time when feminists fought for women’s access to higher education and the medical profession. The Black photographer Charlotte Paige Carroll presented herself as a self-determined businesswoman and professional photographer, thereby challenging intersecting racist and sexist ideas about class, gender, and respectability.

Working with Images: Contextualizing Visual Forms, Noticing Production Processes, Tracking Reception

There is no single correct way of studying historic images from a gender historical perspective. As with other sources, historians will always historicise, contextualise and compare. They will be interested in the materiality of images and the processes of production, in actors and their intentions, in ideas, (visual) discourses and conventions.[5] Images can be studied because they are part of discourses in which contemporary gender ideals were represented and glorified or, as mentioned above, challenged. But they can also be studied to learn more about the ways in which people embodied gender, how they performed masculinities and femininities and sometimes even transgressed conventional gender binaries.[6]

This dossier cannot do justice to the many productive ways in which images can and should be used when studying gender in a historical perspective. Their full potential has not been reached because historians are typically not well-prepared for interpreting images, since our professional education tends to focus on text-based sources. We need to cross disciplinary lines to learn from art historians and others who work with images. However, historians bring a variety of discipline-specific questions, sensibilities and ways of seeing to their analysis that are pushing us to develop discipline-specific reflections on methods for using visual sources to do gender history and for addressing the challenges that this entails.

Contextualizing Visual Forms

Visual sources of all types – drawings, photographs, posters etc. – are (like historical sources in general) not sui generis. They are created within a universe of visual conventions particular to their time and place, almost like another language that was available to contemporary viewers but might elude the historian. Therefore, we need to interpret images in the context of their particular “visual universe,” to attend to questions about the conventional presumptions of producers and audiences. How can we discern how the image in front of us relates to others in its category? What sort of canonical images might have influenced the creation and reception of the particular image we are reading? When was the image’s producer following formal conventions, and when did they depart from them? And, of course, we must historicize these conventions even as we note how the conventions of our own times influence how we see a particular image!

These types of questions are at the heart of art-historical analyses. In this dossier they are applied to images not usually or necessarily considered “art” but still highly influenced by genre conventions. Hence, Mooney draws on the conventions of early 20th century “vernacular photography” to frame her analysis. She discusses the work of the photo historian Brian Wallis to draw our attention to generic characteristics that shaped how Carroll’s photographs were produced and received in their context: “Vernacular photographs ‘are defined more by their destination than their origin,’ with most intended for the private album than public exhibition.”[7] However, images travel and can take on new meanings. As Mooney points out, “institutions today are actively collecting and displaying Black photography to address the racist exclusion of African American histories from their collections. In doing so, they shift the value and narrative of both amateur and professional photographs, broadening the meaning of the term ‘vernacular’.” Maynes places her analysis of the work of women comics in the context of a history of the comic form, a history that until very recently was largely the work of literary and art historians, and, even in those disciplines, marginalized. She draws on their research on women comic artists to show, for example, how women artists subverted the genre’s conventions to reimagine “women and girls normally drawn by male artists [who] rebel against their characters’ limitations.”[8]

Noticing Production Processes

Historians are generally more interested in the content of images and in the subject represented than in the subjects who produced the images and the process of its production. This is understandable; however, delving into the production process can offer a lot to historians of gender. On the one hand, this might point to processes of exclusion that, for example, made it difficult for women to become professional photographers. For all their variety and heterogeneity, images are not representative of all perspectives. On the other hand, asking questions about how particular visual sources came to be, can lead to evidence of communication processes and networks of interpersonal connections that might have served as tools for building communities, and for challenging the limitations imposed by the gender order.

While such processes are crucial for gender history, they are by no means easy to reconstruct. Rarely do we know who designed propaganda posters or who produced medical or other scientific drawings. Looking at archival collections of photographs, Mooney notes that “the identity of the subject of the photograph is prioritized over the photographer’s name, address and other details.” For the historian, “the near erasure of this pertinent information in what Antoinette Burton refers to as the critical ‘backstage of the archives,’ [9]including catalogues, finding aids and more recently databases”, makes it very difficult to reconstruct production processes and authorship. In terms of her work with illustrations in children’s literature, Bruce notes a similar frustration: of the three works she focuses on, “only Hoffmann, who drew his own illustrations, is credited as illustrator – otherwise, I do not know much about the artists.”

But still, when possible, analysis of the production of images can bring new insights. Despite the challenges, Mooney persists in digging into Carroll’s life and connections and cultural world. She speculates about the interplay of image and text on her business card to capture the aims and views that shaped Carroll’s photographic opus: “Carroll’s assertion speaks to the paucity of peers and opportunities, projecting a profound sense of accomplishment despite prejudicial circumstances […] she gives reasons for patronizing her studio that correspond with the development of many ‘Don’t buy where you can’t work’ … campaigns that sought to thwart racist businesses while unifying diverse segments of African American populations.” In her essay, Maynes calls attention to the social and political world of women comic artists – most notably the collective around the production of Wimmen’s Comix – before analysing the gendered content of their works. She notes that the inclusions and exclusions, and the debates that shaped the world of women comic artists bring a whole new dimension to our understanding of second-wave feminism in the U.S. and transnationally.[10]

Tracking Reception

As we have just argued, taking production processes into account when analysing images is challenging; tracking reception – addressing questions about how historical images were received – is often close to impossible. Still, considering reception, insofar as the sources allow, is crucial for understanding how images work – what messages are received by viewers, how they work on the viewer as a gendered being. Even where direct evidence is scant, there are forms of documentation that might offer clues about reception: popularity, circulation in private networks or in publications, reports of scandals or disagreements resulting from the circulation of specific images, private and public collection of valued images, etc.

For some of the visual sources examined here, it is possible to analyse reception relatively directly. Maynes was also able to consider questions about the reception of women’s comics, in some circles at least, because of the documentation of debates over them, and the interest in them of art historians and journalists who provide evidence about reception. Drawing on this comic history scholarship, Maynes noted the mixed reception of Wimmen’s Comix among various audiences, even within feminism. She draws on the work of Sagan Thacker, whose research demonstrated that some feminist reviews praised the innovative comic form, thus “leading one to believe that comics […] were viewed as a valid form of feminist rhetoric within the [feminist] community,”[11] even while it also documents other feminists’ disdain for comics. The literary scholar Susan Kirtley called attention to “a particularly hurtful example” of negative reception – “the mainstream feminist magazine Ms. refused to run Wimmen’s Comix ads,” in a specific rejection of the particular forms of visualizing gender relations that were emerging from the feminist underground comics movement.[12] In the case of the popular handbooks studied by Benninghaus, relative failure to sell as well as exceptional commercial success are suggestive of readers’ preferences and interests. And the very fact that such handbooks still exist in vast numbers (and often in very poor physical conditions) point to the countless times in which they have been used.

For some visual sources, documents about reception are rare. This is especially true of images directed toward marginalised audiences, such as the German children who were the target audience for book illustrations, or the “backward” peasants toward whom the Soviet posters were directed. For her study of vernacular photographs, Mooney drew on shreds of evidence to speculate about reception and “Black spectatorship”: “These images reflect choices not only made by photographers and subjects but also by viewers, publishers, collectors, archivists, and future researchers […]. In publishing their portraits in the pages of the Chicago Defender and other news media, women such as educator Oneida Cockrell or YWCA chairman Freda Cross gave over their likenesses to the public sphere, participating in the scaffolding of the politics of respectability, modelling the possibilities of economic mobility and personal achievement.”

Putting Images to Work – some Ethical Considerations

Historians usually quote from their sources. We want to share the evidence we have dug up, we want to explicate and justify our interpretations, and we want to indulge our readers by offering them a taste of the historic flavours we all cherish. However, when working with visual materials, historians need to keep in mind the power of images – their impact on their original audiences, on us as historians, and on the viewers among whom we re-circulate them. This is a problem not specific to gender history. But given the ubiquity of injustice and inequality so important to gender relations, quoting from the visual archive easily becomes a fraught undertaking.

Some photographs might have been produced in abusive situations (for example, those that objectify medical patients or document murderous violence). They own their existence to the violence they depict, so how can we reproduce them without repeating this very violence?[13] Especially hitherto unpublished or rather obscure images are brought into the open and might take on a life of their own when published on the internet. They can easily take on new meanings as they leave the context in and for which they were once produced. And all our attempts at contextualisation and deconstruction might become useless when they are deliberately or accidentally taken out of context. Conventions change and audiences matter: drawings perceived as comic satire in one era might shock and offend viewers in another setting. Images meant for private consumption might be rather painful to see on a big screen in a professional setting. Showing and analysing images as part of the project of doing gender history, as we argue, can bring us powerful new insights. But, precisely because of the power of images, it is crucial to attend to the ethics of their circulation and re-circulation across time.

[1] “Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive,” Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, Genders, and Sexualities, July 2, 2023, Santa Clara, CA.

[2] See e.g. Saidiya Hartman’s interpretation of a photograph of a young black girl: Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval, New York 2019.

[3] On the ambiguity of images, the plurality of possible meanings and the impossibility of discovering the meaning of an image, see: Stuart Hall (ed.), Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, London 1997, p. 9ff.

[4] Hence, when during the mid-1990s, Georges Duby and Michelle Perrot published the five volume series on “The History of Women”, these volumes were not only illustrated but included essays focussing art and other visual representations. Georges Duby/Michelle Perrot (eds.), A History of Women, 5 volumes, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1992-1994.

[5] See e.g. Ludmilla J. Jordanova, The Look of the Past: Visual and Material Evidence in Historical Practice, Cambridge 2012.

[6] This is especially true for photographs but also applies to other images considered as naturalistic by contemporaries. For examples on queer and trans*representation see e.g. Jennifer V. Evans, Seeing Subjectivity: Erotic Photography and the Optics of Desire, in: The American Historical Review 118.2 (2013), pp. 430-462; Katie Sutton, Sexology’s Photographic Turn: Visualizing Trans Identity in Interwar Germany, in: Journal of the History of Sexuality 27.3 (2018), pp. 442-479.

[7] The work of historians of photography helps Mooney to establish the context for analysing Carroll’s photographs. See: Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers, New York 1986, republished 1993; Brian Wallis, The Dream Life of a People: African American Vernacular Photography, in: idem, African American Vernacular Photography: Selections from the Daniel Cowin Collection, New York 2005, pp. 9-14; and Geoffrey Batchen, Vernacular Photographies, in: idem, Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History, Cambridge 2000, pp. 57-80.

[8] See: Susan Kirtley, “A Word to You Feminist Women”: The Parallel Legacies of Feminism and Underground Comics, in: Jan Baetens/Hugo Frey/Stephen E. Tabachnick (eds.), The Cambridge History of the Graphic Novel, pp. 269-285; and Sagan Thacker, “Something to Offend Everyone”: Situating Feminist Comics of the 1970s and ‘80s in the Second-Wave Feminist Movement, Senior Thesis, The University of North Carolina at Asheville, 2020, online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1frESdfMyMWm5teThK3FRH6UZf_6pthy8/view [02.10.2025]

[9] Antoinette Burton, Introduction: Archive Fever, Archive Stories, in: idem (ed.), Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History, Durham, NC 2005, p. 7, online https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/989/chapter/147400/IntroductionArchive-Fever-Archive-Stories [02.10.2025].

[10] See: Leah Misemer, Hands across the Ocean: A 1970s Network of French and American Women Cartoonists, in: Frederick Luis Aldama (ed.), Comics Studies Here and Now, New York 2018, pp. 191-210.

[11] Thacker, Situating Feminist Comics, p. 13.

[12] Kirtley, Parallel Legacies, pp. 274-275.

[13] For an astute discussion of the problems involved in quoting from the colonial archive (also with regard to gender) see Anne D. Peiter, Die Ethnogenese und der Tutsizid in Ruanda. Überlegungen zum kolonialen Erbe mit Blick auf die deutsche Kolonialfotografie, in: Visual History, 04.06.2024, https://visual-history.de/2024/06/04/peiter-die-ethnogenese-und-der-tutsizid-in-ruanda/ [02.10.2025].

This article is part of the theme dossier “Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive,” edited by Christina Benninhaus and Mary Jo Maynes.

Theme Dossier: Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive

Zitation

Christina Benninghaus und Mary Jo Maynes, Introduction. Putting Images to Work: Constructing, Complicating and Subverting Gender, in: Visual History, 06.10.2025, https://visual-history.de/2025/10/06/benninghaus-maynes-putting-images-to-work-gender-and-the-visual-archive/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2951

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Eine Nutzung ist für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in unveränderter Form unter Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de