Ambiguous Representations of Gender in Late Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century Illustrations in German Children’s Literature

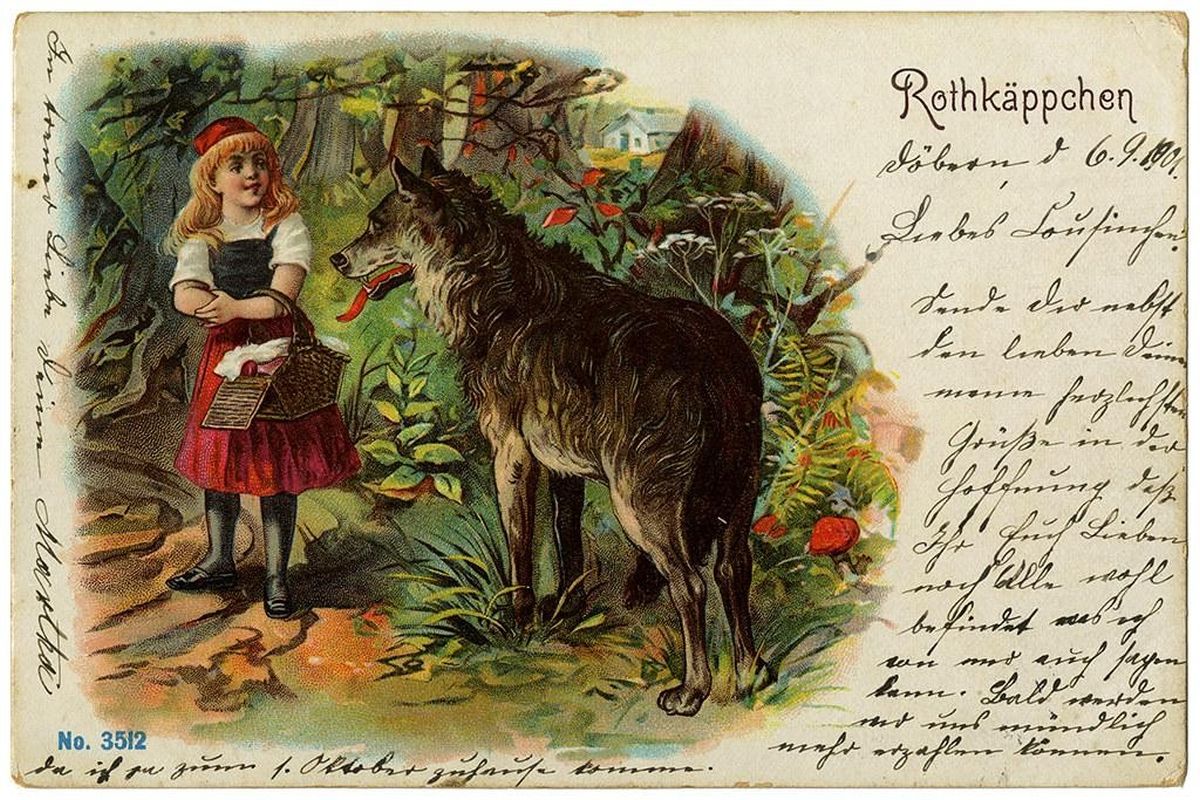

Rothkäppchen (Little Red Riding Hood) postcard (1901) Source: The Jack Zipes Historic Fairy Tale Postcard Collection, Minneapolis College of Art and Design

In his landmark book “Words about Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books”, Perry Nodelman explores how context and form script an image’s message. Contemplating Maurice Sendak’s 1962 illustrations of Charlotte Zolotow’s story Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present, Nodelman writes, “we are not disturbed by [a giant rabbit encountered by a child] simply because picture books so frequently depict animals. In a painting hung in an art gallery, an animal leading a little girl down the garden path might have powerful sexual connotations; in a picture book it hardly attracts our notice. Perhaps it should, however.”[1]

He then muses on the “surprisingly rich ambivalence” in Sendak’s presentation of animal and girl that do evoke some menacing undercurrents alongside a gentle text. He does this by bringing in the intertextual power of “Little Red Riding Hood.”[2] That story, which has prompted endless sexually ambiguous visual interpretations on page and screen, was transformed from an oral tradition for adults to a classic of children’s literature during the early nineteenth century in Central Europe – the time and place of this essay’s focus.

My own analysis of ambivalent representations of gender and sexuality in children’s book illustrations centers on publications for middle-class German readers between 1776 and 1845 – a somewhat overlooked yet foundational milieu of modern children’s literature. I have found that these images at times invoke hegemonic ideas about gender while at others deviate from those norms – occasionally even within the same text. Materials created explicitly for children and youth offer special insight into ideologies such as those that structure gender and sexuality. This is true both because they can be more heavy-handed in their ideological messages – with a mind toward what is appropriate for the child viewer – but also because they remind us of the limits of didacticism when we consider the young reader’s/viewer’s unpredictable response. Thus, ambiguity is itself a characteristic of the gendered values presented in children’s books. At various historical moments, children’s illustrations upheld expectations of adult visual culture while breaking or sidestepping others.

I argue that especially in European children’s books of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, we see a mosaic of both emancipatory and essentialist notions about girls’ place in the world, before a more uniform gender ideology coalesced in the later nineteenth century for mainstream children’s literature.[3] After a brief history of relevant technological and social developments in German children’s literature, I examine gender dynamics in three examples drawn from different genres of illustrated texts for children (youth periodicals, schoolbooks, and fictional short stories). Surveyed together, what do these texts tell us about how the illustrations of books written for German children of the educated middle class reinforced or broke away from prevailing gender ideology?

German Children’s Literature before 1845

To appreciate the ambivalent and contradictory messages about gender in earlier children’s illustrations, we also need to know something about the texts that they accompanied. What else was in front of the bourgeois child reader’s eyes? The so-called “Golden Age” of European children’s literature did not take off until the late nineteenth century,[4] when technological advancements led to a surge in picture books and illustrated chapter books with greater artistic ambition than those of earlier eras. Color illustrations and covers were not common before 1840.[5] And copyright protections for authors and illustrators did not become widespread in Europe until the turn of the twentieth century.[6]

But the title that is considered the first illustrated book for children was published much earlier – 1658 – and in Central Europe: Johann Comenius’s “Orbis Sensualium Pictus” (The Visible World in Pictures).[7]

Johann Amos Comenius, Orbis Sensualium Pictus, Nürnberg 1658 (The Visible World in Pictures). Source: Wikimedia Commons

This text has been “the greatest children’s book of the seventeenth century.”[8] It was formally bilingual (in Latin and German), but Katie Trumpener has pointed out that its illustrations constitute a third language to help young readers interpret the natural and social world.[9] It influenced the later development of illustrated children’s books, schoolbooks, and encyclopedic nonfiction published to amuse and instruct child audiences.[10]

Comenius held views about education that might seem ahead of his time, including that all children – girls and boys, of any social stratum – should attend school. Robert Dent persuasively ties these attitudes, and the intense efforts Comenius gave to pedagogy, to his Millenarian spirituality and membership in the Bohemian Brethren (the early Moravian Protestant church, which was unusually egalitarian).[11] Meanwhile, Margaret Higonnet frames the “Orbis Pictus” as an imaginative travel narrative, in which Comenius invited child readers to visualize the book as their path into the world. This is a striking contrast to the “Golden Age” division of domestic stories (for girls) and travel or adventure stories (for boys).[12] Per Comenius, both girl and boy readers could travel the globe – at least in their imaginations.

We still have much to discover about the part that images played in readers’ experiences during this early era of less regulated, less standardized publishing for children. Perhaps the most promising period for further exploration is the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. At that time, Western Europeans moved from intensive reading of only a few religious books, largely in Latin, to extensively reading a wide range of increasingly secular books, often in vernacular languages.[13] Institutions supporting the book trade grew rapidly in this period, including specialized printers, publishers, and booksellers, new journals for book reviews, and fairs such as the great biannual Leipzig Book Fair, which was longstanding but expanded in the eighteenth century.[14] In 1755, the Leipzig catalog included 1,231 titles; by 1795, 3,368 books were listed.[15]

As the market share of religious texts declined from 1740 to 1800, pedagogic texts became one of the top genres sold.[16] In 1775, the busy publisher and bookseller Friedrich Nicolai wrote in a review: “We are beginning to receive a great wealth of writings for young people […] thus the young soul finds here such matters through which it must be awakened to the fear of God and love of humanity, once it is able to accept good thoughts and sentiments.”[17] Increasingly, such writings were also illustrated, from a minimum of borders and ornamentation between sections, to a frontispiece, to interleaved plates. The more elaborately illustrated books sometimes received comments on their images’ artistic and technical quality by reviewers like Nicolai.

New technologies emerging during this era included marketing innovations, such as Johann Cannabich’s “Kleine Schulgeographie” (Short School Geography, 1818 to 1851) which advertised an accompanying school atlas from the same printer on its title page (as well as the price).[18] Books, including illustrated ones, became cheaper in the early nineteenth century. The development of the more powerful iron press made reproducing woodcuts easier, and the handpress in general was soon on its way out in favor of mechanization.[19] Penny Brown has shown how the rise of illustrations in French children’s books after 1770, while of course made possible by technological change, was also driven by desires to spread new Enlightenment ideas about childhood.[20] These included, for example, innovative images of children interacting without adult supervision.

Title page of Johann Günther Friedrich Cannabich’s “Kleine Schulgeographie”, Weimar 1851.

Source: Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsmedien Georg-Eckert-Institut, Braunschweig

Despite Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s denunciation of books as “sad furnishings” for a boy’s world, even his followers such as Joachim Heinrich Campe were convinced that supplying children with more, tailor-made reading experiences was essential to their self-formation.[21] Experts had begun to consider illustration a key element of this specialized literature. In this “pedagogic century” between 1750 and 1850, European philosophers placed the child as symbol at the center of political discourses about reason, governance, and the self; at the same time, some directed their attention to children’s own development, reimagining childhood as a vital stage of life separate from adulthood.[22] Pedagogues across the continent debated and lectured parents about age-grading, sentiment, literary quality, religion, language, and even the proper binding for the books they should offer their children, as well as under what conditions children should read.[23]

This era also witnessed the rise of several new genres, or genres newly redirected for young readers. For bourgeois children, the curriculum both in institutions and for informal learning at home expanded from the medieval trivium (grammar, rhetoric, and logic) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music) to include new academic fields such as natural science, geography, and world history. Schoolbooks could also provide instruction in letter writing, manners, and comportment, and even dance patterns.[24] From a catechetical model in the mid-eighteenth century – for which readers were assumed to be elite young men – a participatory, problem-driven model emerged in schoolbooks, for which the particular needs of child readers were considered, including their age, gender, and desire to be amused.[25] That meant that visual elements such as atlases and illustrations were increasingly critical to support both problem-solving and entertainment. It also motivated authors and publishers to produce what they believed boys or girls of different ages should see in ways that fit their age and gender.

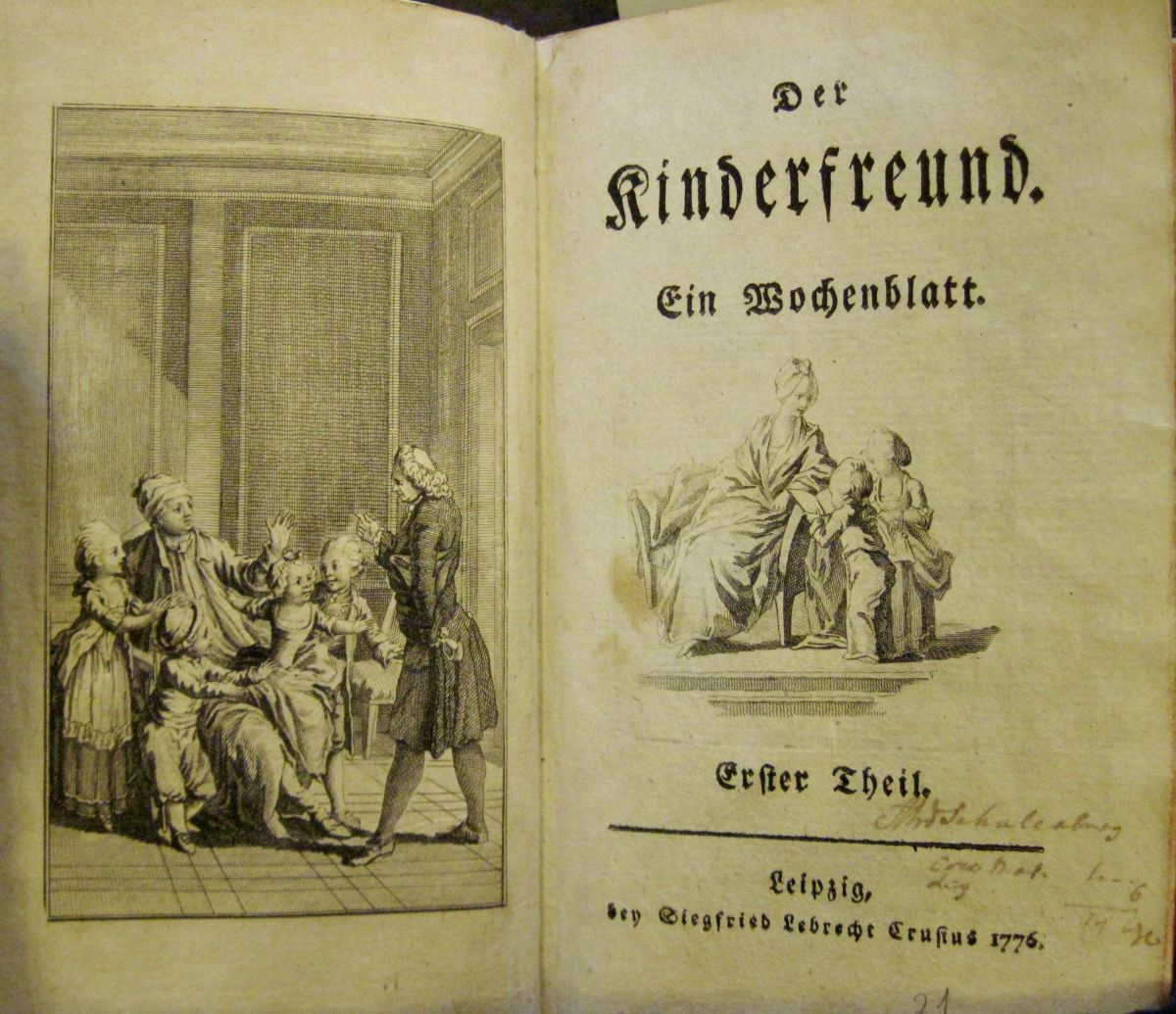

Academic and moral instruction for bourgeois European child readers arrived in another new genre at the end of the eighteenth century: youth periodicals. Taking off in the 1770s in Central Europe, these magazines, weeklies, and yearbooks capitalized on the power of print and expanded literacy to deliver a hodgepodge of poetry, serialized fiction, riddles, games, theology, history, botany, fables, and more directly to children.[26] These texts were almost always illustrated, at the very least with miscellaneous floral and classical motifs as ornamentation. Sometimes they included rich frontispieces either “borrowed” from circulating engravings or crafted anew for each issue. The quintessential youth periodical, Christian Felix Weiße’s enormously influential weekly “Der Kinderfreund” (The Children’s Friend, first published 1775) spread quickly around the world.[27] In 1775, Weiße addressed his young readers directly, pleading that “the appetite with which you will collect [this publication] from the publisher and read it will soon persuade me whether I should continue these little family amusements or should break it off.”[28] Serialization, subscription, and illustrations helped position the book as an indispensable commodity that the middle-class child should desire.

Gendered Illustration in German Children’s Books: Three Examples

The subsequent analysis is inspired by the collective questions of this dossier: How have historical actors used images to confront, challenge, problematize or undermine hegemonic gender concepts? For whom and under what economic and technological conditions could various types of images become a means of expression and contestation, and how did they circulate in these societies? To that end, I will scrutinize examples drawn from three texts of this era: The Children’s Friend by Weiße; an 1823 schoolbook, Luise Hölder’s Short World History … for Children from 6 to 12 Years; and Heinrich Hoffmann’s famous 1845 parody, Struwwelpeter.[29] Only Hoffmann, who drew his own illustrations, is credited as illustrator – otherwise, I do not know much about the artists. Together, these three texts demonstrate that illustrations in children’s books of this era presented an opportunity for surprising, and sometimes even transgressive attitudes toward gender and sexuality.

Christian Felix Weiße, Der Kinderfreund: Ein Wochenblatt für Kinder (The Children’s Friend),

Leipzig 1775-1782. Source: Cotsen Children’s Library, Princeton

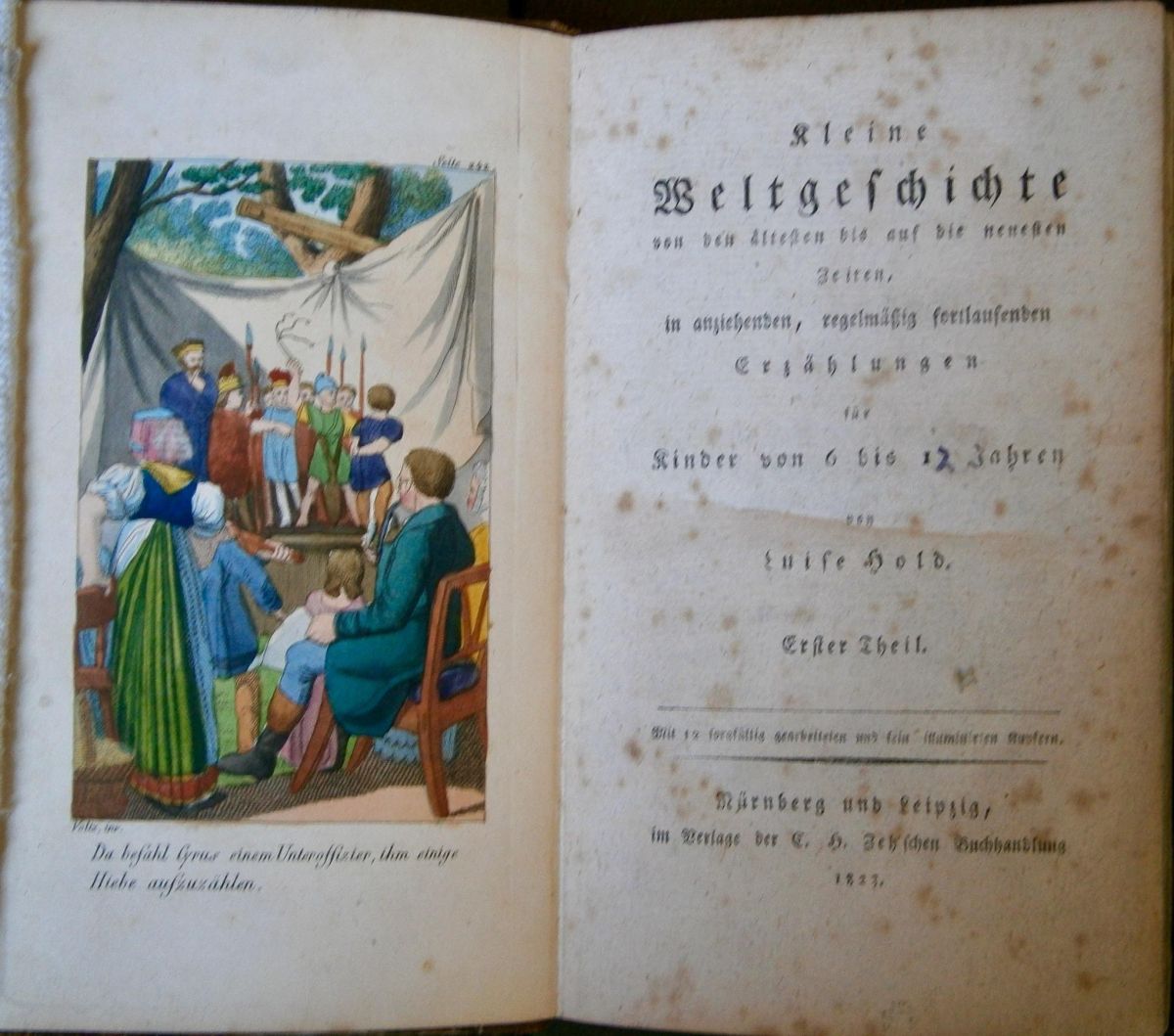

Luise Hölder, Kleine Weltgeschichte von den ältesten bis auf die neuesten Zeiten, in anziehenden,

regelmäßig fortlaufenden Erzählungen für Kinder von 6 bis 12 Jahren, Nürnberg 1823

(Short World History … for Children from 6 to 12 Years). Source: Cotsen Children’s Library, Princeton

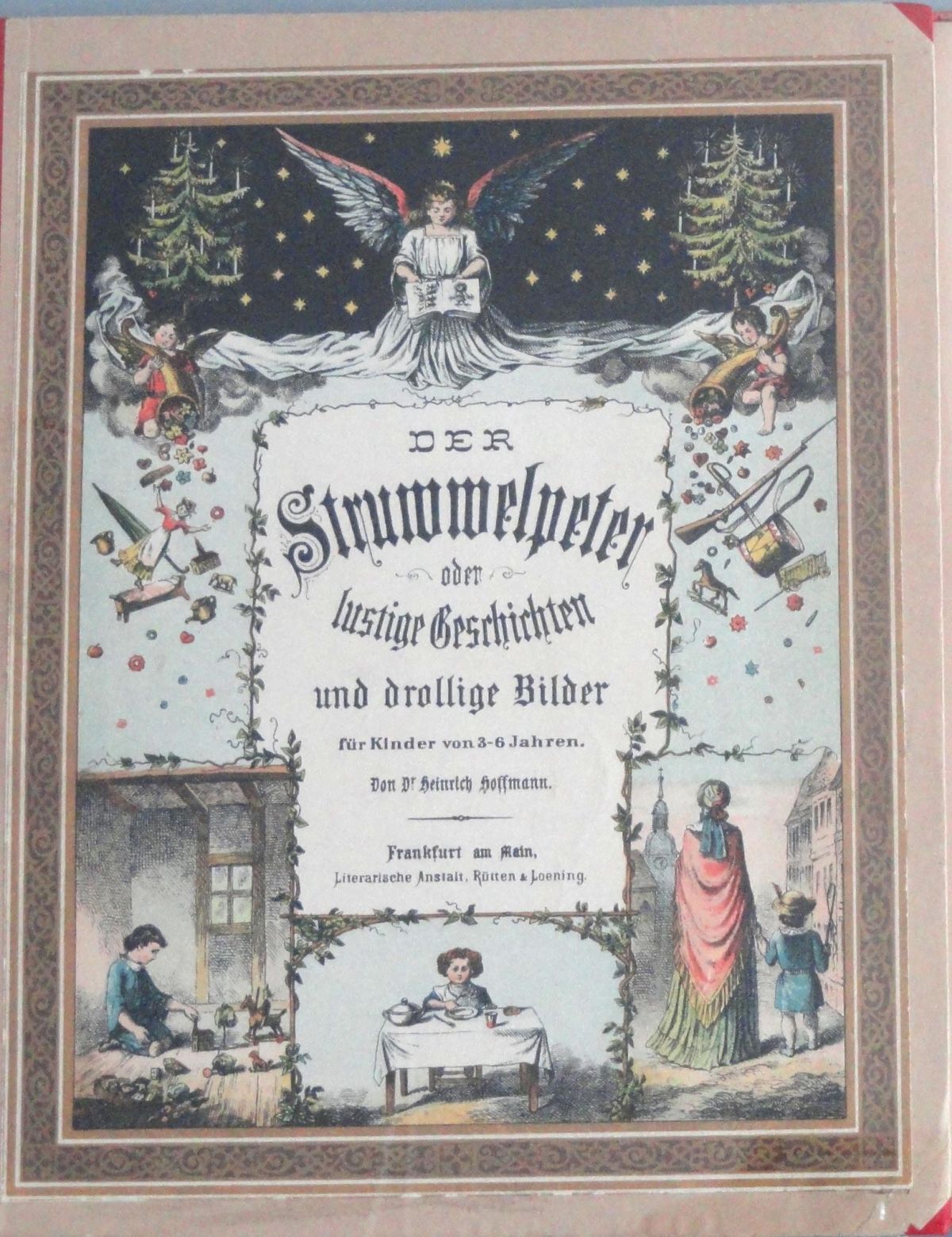

Heinrich Hoffmann, Der Struwwelpeter [Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder], Frankfurt am Main 1845

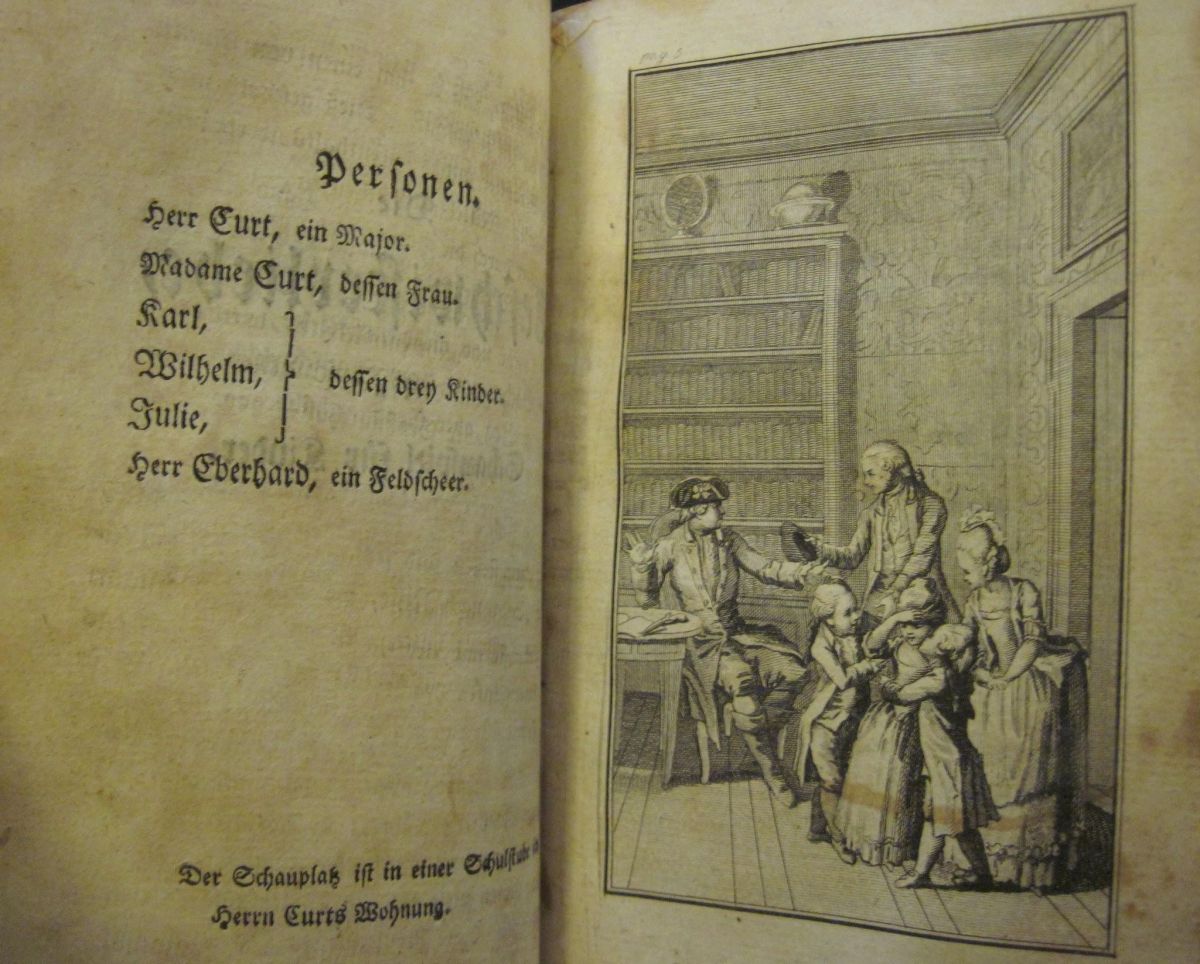

Christian Felix Weiße, Cast list and facing illustration of “Die Geschwisterliebe” (Sibling Love),

in: Der Kinderfreund (The Children’s Friend), 1776. Source: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

In seven short scenes, “Sibling Love” tells the story of a boy named Karl accidentally shooting his sister Julie with a gun. The rest of the action shows Karl’s siblings (including poor wounded Julie herself) lying to take the blame with their enraged father. Struck by their loving defense of one another, the father eventually forgives them all and Julie makes a miraculous recovery. Karl’s nearly fatal error is excused as willfulness to be expected of boys; extraordinary self-sacrifice is expected of girls.

Weiße often used this form of sentimental drama as an instrument for eliciting and managing the child reader’s affective response. Here, the illustration reinforces both the key action of the drama and essentialist gender norms. Centered in the foreground, the wounded, weak Julie is supported on either side by her manly little brothers. In this sentimental age, the kiss of the brother on the right was consistent with bourgeois masculinity, particularly between close friends or family and particularly for little boys.[30] Meanwhile, the men standing behind the children are physically and verbally active, debating the just outcome, while the woman quietly leans forward in a posture of tender care. Just as the children are dressed in miniature versions of the adult fashions, their manners and relations mimic the expected behavior of men versus women for child readers.

But on other occasions Weiße included girls in The Children’s Friend periodical in surprising ways, contradicting our assumptions about their restricted education. Here are a pair of examples that demonstrate this:

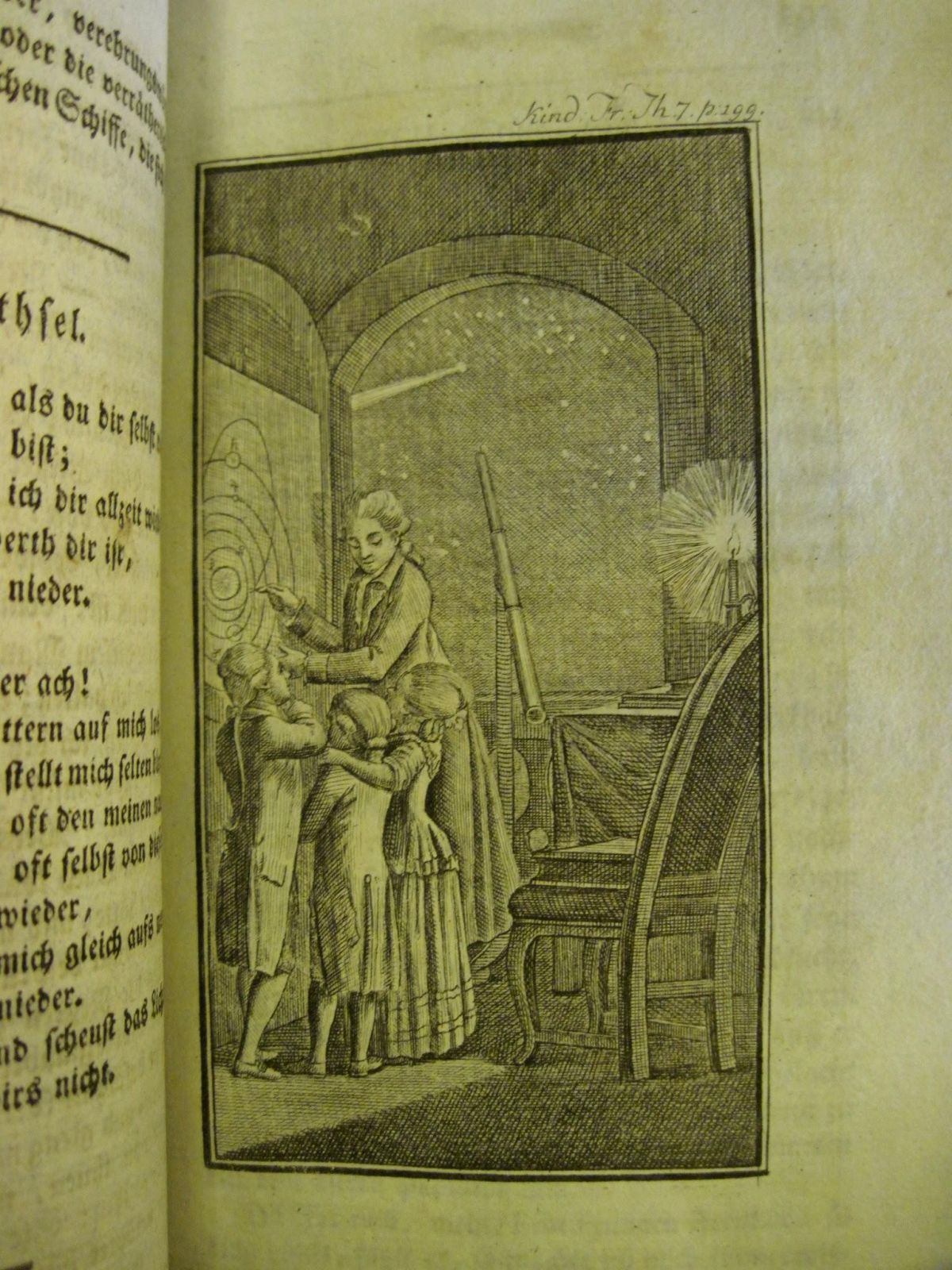

Christian Felix Weiße, Der Kinderfreund (The Children’s Friend), 1781

In the first, we see an affectionate trio of siblings receiving the same astronomy lesson from their tutor. The elder brother gazes at the sky itself, performing that independent observation so critical to the scientific method and Enlightenment pedagogy. But both younger children are focused together on the tutor’s diagram, without any hint of difference in the content or purpose of learning for brother versus sister. Perhaps this is unsurprising, given the long history in early modern Europe of training women as astronomical helpmeets (technicians and calculators) for a discipline that was based on in-house telescopes.[31] Still, the message in this illustration, at least, is one of gender equality in scientific inquiry. The instructor seems equally engaged with all three children – if anything, his line of sight is directed at the girl while he gestures to the explanation of orbits. Once again, the illustrator has portrayed an easy physical affection between siblings which suits the “homey,” comfortable context of informal middle-class education in this era. But the girl’s arm draped around her brother’s shoulder only brings her into the scientific moment rather than excluding her.

The style of the plates in The Children’s Friend – with ordinary subjects rendered fairly precisely and on a small scale – encourages a realistic or “naturalistic” reading. Even though these pre-French Revolution children are shown dressed largely in miniature versions of their parents’ fashion, with formally arranged hair, long frock coats and stockings for the boys, and structured silhouettes for the girls, their bodies are nevertheless represented with soft lines and relatively simple adornment. This hints at the bourgeois aim of resisting aristocratic “artificiality.”[32] As images of bourgeois children, the characters are presented in a far less rigid, formal fashion than young aristocrats (criticized for their artificiality) would have been; we also see far less gender distinction marked on the bodies than would become evident later, in the nineteenth century.

In the second example, both boys and girls are occupied together in mounting family theatricals. We see a range of ages, including one tiny girl wearing spectacles. Different personalities are represented through varying forms of engagement with the exercise and different dramatic roles. But these variations are not attached to any particular gender rules. Performances at home – what Pamela Gay-White and Adrianne Wadewitz call “socializing theater in the domestic sphere” – welcomed the participation of girls and boys across Europe in this era.[33] The stories and language of any given drama might have reified gender difference. Nevertheless, by frequently including this genre in the new youth periodicals, pedagogues such as Weiße invited girls and boys alike to participate in the bourgeois literacy project, just as is indicated in this illustration. Given the historical gender disparity in literacy rates and education, that is no small thing.

Turning now to schoolbooks: the following examples come from the 1823 world history text. Rather than depicting the subjects of the narrative with typical classical imagery, the illustrations throughout this text show children themselves dressed up as the historical figures and brandishing odd bits of props to act out the scene. This paradox of adults didactically encouraging creative and independent play from children is a hallmark of middle-class childrearing during the Age of Revolutions.

Luise Hölder, Kleine Weltgeschichte von den ältesten bis auf die neuesten Zeiten, in

anziehenden, regelmäßig fortlaufenden Erzählungen für Kinder von 6 bis 12 Jahren

(Short World History … for Children from 6 to 12 Years), Nürnberg 1823

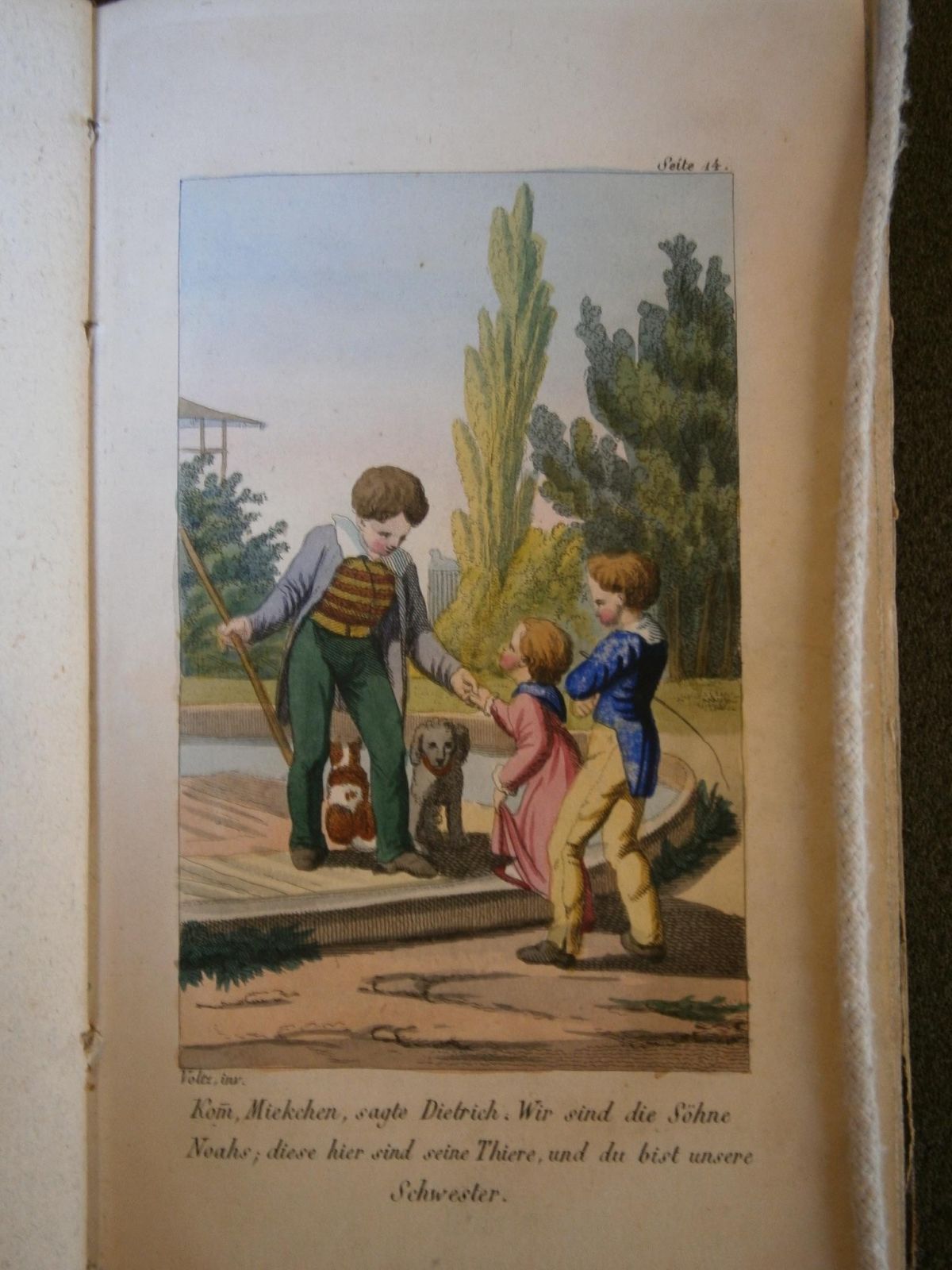

“‘Come, Miekchen,’ said Dietrich. ‘We are the sons of Noah; these here are his animals, and you are our sister.’”

Luise Hölder, Kleine Weltgeschichte von den ältesten bis auf die neuesten Zeiten, in

anziehenden, regelmäßig fortlaufenden Erzählungen für Kinder von 6 bis 12 Jahren

(Short World History … for Children from 6 to 12 Years), Nürnberg 1823

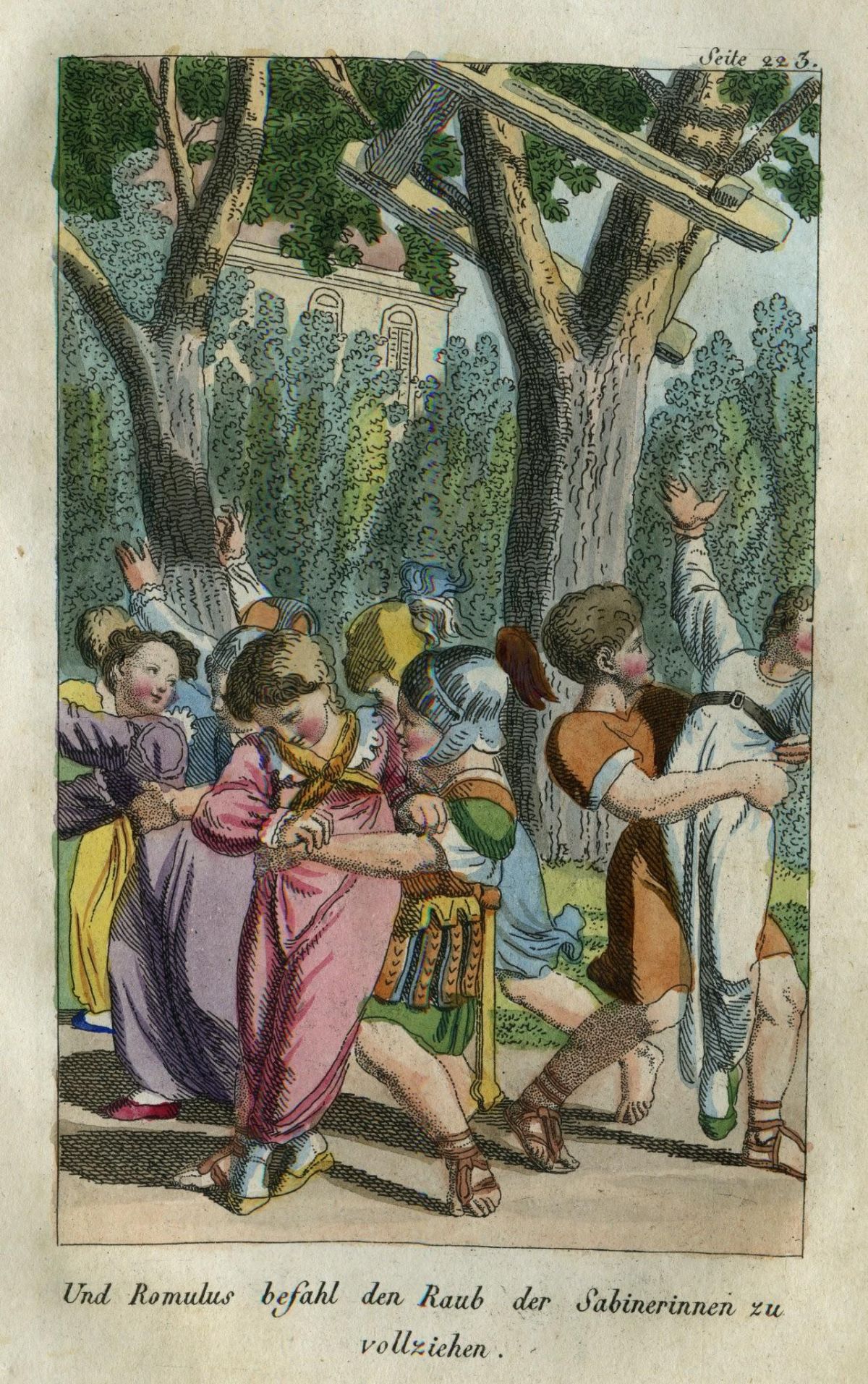

“And Romulus ordered [them] to carry out the Rape of the Sabine women.”

In her Short World History, Hölder promotes a mother-centered approach to early childhood education, similar to that of her contemporary Friedrich Fröbel (father of the Kindergarten movement).[34] This logic, which would drive “maternalist” feminism later in the century, carries its own ambiguity.[35] Proponents justified a role for bourgeois women in fields otherwise dominated by men (in this case, publishing history textbooks) as the legitimate advising of other mothers in their social class. But this left women authors confined conceptually by gender essentialism. Hölder claims space for herself as an expert scholar and teacher by deploying a frame narrative for her textbook. It opens with the story of a young girl begging her mother for geography and world history lessons, so that she, Miekchen, can relay them to her playmates.

In the first example illustration, a caption explains the ringleader’s plan as he directs his siblings and pets in play-acting Noah’s Ark.[36] The directorial power of the elder brother, William, is clear from his posture in the image, bending down to take Miekchen’s hand and bring her onto the “Ark,” as well from as the imperative verb of the caption. Yet the illustrator also suggests that it is appropriate for the boys to include their sister in this imaginative historical amusement. She is certainly a participant in enacting this Bible story, standing in the center of the group of figures.

When juxtaposed with the text, the invitation of girl readers to active learning alongside their brothers becomes more murky.[37] The frame narrative presents Miekchen coming to her mother’s workroom to learn the history of Noah, but this time in a terrible state: sometime after the moment depicted in the illustration, she ended up in the water and was a “hair’s breadth” from drowning. Her mother asks how she could have been so “thoughtless” (unbedacht), and it comes out that it was the boys’ idea to put her on a board floating in the cistern along with the family cat and poodle as Ark passengers.[38] Then Dietrich also wanted to get on the board and overturned her. The episode ends with Miekchen’s dramatic descent into fever (with chastened brothers at her bedside) and equally fast recovery. So, was this kind of child-led, play-based study of history recommended for little girls or not? Is the episode simply a dramatic veneer intended to entice readers into the drier pages, so to speak? I argue that, when combined with the illustrations, the text tends toward endorsing an equally amusing, modern pedagogy for both girls and boys.

A second surprising plate depicts a crowd of little children performing the abduction of the Sabine women.[39] This example demonstrates an innovation of this new genre of schoolbooks for girls in the early nineteenth century, the partial democratization of access to a classical education once reserved for elite boys. But here, the assault of antiquity is mirrored by a modern betrayal. Miekchen’s brothers have asked her to invite her friends over, promising a peaceful afternoon of garden theatricals. Their dubious mother warns Miekchen that she will not “come to her defense” if the boys do anything “disagreeable” (unangenehm). And in fact, “to the great pleasure of the little spectators, fighting games began and continued for some time; but suddenly the boys came rushing at them with a great rumbling noise and each seized a girl in his arms and hauled her off.”[40] Initially relegated to the most passive position of spectator, the girls are then granted a performative role, but as captives. Yet the negotiation of peace required by the end of this story would suggest some degree of active participation by the girls in this imaginative form of play.[41]

Although the crying girls complain about the naughty (unartig) boys, none of the children are punished. The text simply continues to a recounting of the Romulus and Remus legend, including the Rape of the Sabine Women and its climax of the abductees making peace between the groups on behalf of their now husbands. Any suggestion that the skirmish was poor behavior on the boys’ part is faint in the text, especially compared with the enticement of the vibrant illustration.

It is hard to imagine that the episode is meant to appeal to any young female readers of the text imagining themselves in the little sister’s shoes. What message would the child flipping through these pages in search of the pictures have received about the fitting roles of men and women or boys and girls? In one reading, the sisters are rendered just another prop for their aggressive brothers, analogous to the boys’ pets standing in for historical animals. This is partly tempered by a few examples throughout the text in which Miekchen or other girls are the ones who initiate the reenactments and historical discussions. Furthermore, the illustration is engaging: full of movement, classical allusions, and colors still bright today in archival copies of the book. I suggest that promoting play and amusement as rightful experiences for girls as well as boys is a secondary message of the text. For the second audience of adults (parents and tutors), the boys’ wildness is apparently easily excused as appropriate to their age and gender. However, so is the inclusion of girls in this form of play and storytelling presented as suitable. Indeed, the book implies that reenactment of meaningful events in history is not possible without some representation of women.[42]

My final text, Heinrich Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter (1845), forms something of a bridge from the enthusiastically expanded children’s literature of the years around 1800 to the more sophisticated Golden Age. While it has sometimes been misread as an archaic piece of didacticism, it is really a fantasy and parody of those earlier moralizing stories. The early children’s literature scholar Harvey Darton describes scenes such as the tailor chopping off the thumbs of a little boy who was sucking them as an “Awful Warning carried to the point where Awe topples over into helpless laughter.”[43] Struwwelpeter was almost instantly popular across translations and has had more staying power than most of its Enlightenment predecessors.[44]

It also marks the beginning of new practices in the children’s book market. Hoffmann insisted to the publisher that it be made available at an inexpensive price.[45] It led to one of the first German copyright cases, sparked by another publisher’s plagiarism.[46] The author-illustrator is known to have closely supervised the lithographer “lest he improve [his] dilettantish figures artistically and stray into the ideal.”[47] In other words, the seeming chaos of his style was certainly intentional. Unlike the work of his predecessors, Hoffmann’s text was rarely severed from its iconic images.

Heinrich Hoffmann, Der Struwwelpeter [Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder], Frankfurt am Main 1845

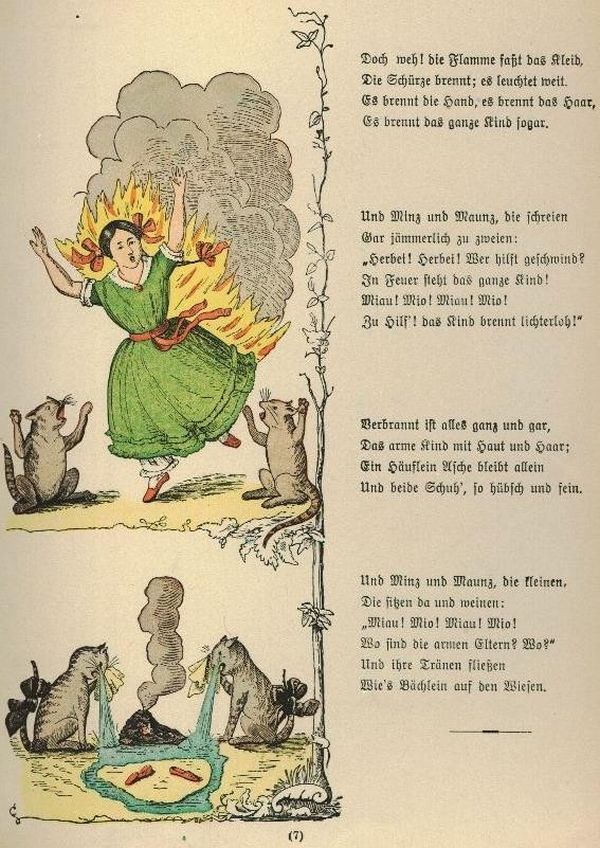

[after playing with matches]

And see! oh, what dreadful thing!

The fire has caught her apron-string;

Her apron burns, her arms, her hair –

She burns all over everywhere.

Then how the pussy-cats did mew –

What else, poor pussies, could they do?

They screamed for help, ‚twas all in vain!

So then they said: “We’ll scream again;

Make haste, make haste, me-ow, me-o,

She’ll burn to death; we told her so.”

So she was burnt, with all her clothes,

And arms, and hands, and eyes, and nose;

Till she had nothing more to lose

Except her little scarlet shoes;

And nothing else but these was found

Among her ashes on the ground.

And when the good cats sat beside

The smoking ashes, how they cried!

“Me-ow, me-oo, me-ow, me-oo,

What will Mamma and Nursey do?”

Their tears ran down their cheeks so fast,

They made a little pond at last.

Struwwelpeter seems at first glance not particularly concerned with gender. Hoffmann was generally more interested in boys, yet there is nothing particularly confining or gender-stereotyped about this naughty girl, Little Pauline, who plays with matches and then burns up, in comparison with the other tales of misbehavior and woe that he presents. Just like Robert, who goes outside during a storm and is whisked away by the wind, or Konrad, the thumbsucker, whose digits are cut off by a tailor with oversized scissors, Pauline misbehaves and reaps an outrageous consequence. She does carry a ladylike doll in the first panel, but it is not described in the rhyming text and is quickly discarded. Patriarchal authority is invoked, but at a distance: Pauline’s father had forbidden her to use the matches, but it is her sing-song kittens who try to warn her about the danger with droll meows. We are invited to shocked laughter on every page of Hoffman’s book, not only on these pictures of poor Pauline.

And yet, clear gender differences remain across the stories and their accompanying illustrations. The reason Pauline gives for her interest in the forbidden matches invokes her future maternal role: “I’ll light a little log as Mother has often done.”[49] Ranging in severity (Pauline is not the only child who meets her end as a result of her actions), the punishments are either natural consequences or enforced by men. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine some of Hoffmann’s boy protagonists swapped as girls, given their more outrageous offenses (such as Friedrich’s violent cruelty toward animals). And while some of the faults that are skewered could have been ascribed to any gender at that time, only the boys had the freedom of movement in this social milieu to get into the scrapes that some did outside the home (such as Hans Guck-in-die-Luft / Look in the air, who accidentally walks into a river).

How should we factor in the parodic nature of Struwwelpeter? The morally didactic literature he spoofed had included naughty girls as well as wild boys, even if some of the commonly censured traits were divided by the gender binary. Some 70 years earlier, the gallery of children’s vices and virtues that Christian Weiße included in The Children’s Friend were somewhat gender marked – more as qualities of mind rather than embodied features that could easily be represented visually.[50] Weiße’s fictional eleven-year-old daughter Charlotte was described as a little frivolous and flighty (feminine flaws), although the author also asserted that she had the capacity for serious learning but chose not to focus. Nine-year-old Karl was the “opposite” of his sister because he was intellectual and serious, and “industrious beyond his years.” He also had a soft heart and was often brought to tears (a manly virtue of the sentimental late Enlightenment). The main fault of seven-year-old Fritz was the wrong kind of cleverness – for example, he was always able to find the biggest piece of cake and persuade his siblings that he suffered with the smallest slice. Finally, five-year-old Luischen was commended for her good memory for stories and picture books.[51]

If this more subtle gendering of virtue lies at one end of a spectrum, and the stark separation of spheres found in much mainstream children’s fiction a century later lies at the other, I see the mixed messages of Struwwelpeter lying somewhere in the middle. This is only reinforced by the comedic excesses of parody, which call into question the “rightness” of any of these punishments. And the wild, amusing images that invite multiple readings further undermine a strong, straightforward lesson about the essential qualities of girls and boys.

Conclusions

Reception looms over any study of the didactic lessons in children’s literature. Questions about how children in the past versus adults in the present read illustrations, or how readers were truly influenced by what they saw, are fascinating, but beyond the scope of this essay. The authors of this experimental age in new texts for young readers certainly believed in their power to affect youth through the tales they read or heard and the images they pored over. In justifying her publication, for example, Luise Hölder wrote:

“There are people who are of the opinion that it is unnecessary that children of six to twelve years old learn something of world history. But in contrast, there is no objection to telling them or letting them read fairy tales or stories of good or naughty children, through which they often develop incorrect notions and become familiar with errors that they could not previously make. Therefore why not rather tell them true events which, in a good education, they must indeed sometime know and study?”[52]

One might observe that reading of the boys’ “wildness” of attacking Miekchen and her friends in the name of studying classical history could help readers “become familiar with errors that they could not previously make.” Nevertheless, Hölder’s claim attests to this era’s faith in the power of books (words and pictures alike) to shape young girls’ and boys’ characters.

In answering the question posed at the beginning of this essay about gender norms in German children’s illustrations of this era, I see an ambiguous picture. The expectations of girls’ and boys’ behavior as expressed in early images are not entirely straightforward, and it was in the adventure stories and domestic fiction of the later nineteenth century that we see more fixed, essentialist depictions. As the literary and publishing norms of children’s literature solidified during the Golden Age, so, too, did representations of a more rigidly divided gender binary come to dominate popular children’s books. Earlier, especially in the late eighteenth century, the market included some surprisingly egalitarian invitations to girl readers to see themselves participating in some version of a bourgeois education alongside their brothers. It also included stereotypical and blatantly misogynist messages, with text reflected in images. And with experiments in genre, style, and the authors’ imagination of their young readers, some illustrations from this earlier era were also simply more ambiguous or contradictory in their portrayal of gender difference.

Together, this flexibility belies one periodization of separate spheres (that beginning with Rousseau) by revealing alternative perspectives on gender through at least the early nineteenth century that were later pushed to the margins within children’s publishing.[53] The finer contours of these developments await a more systematic study of children’s illustration across a longer time period. It would also be intriguing in the future to test these conclusions against an emerging field of study: the analysis of drawings and art done by children and youth, where sources have been preserved.

[1] Perry Nodelman, Words about Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books, Athens, Georgia 1988), p. 118.

[2] Jack Zipes, A Second Gaze at Little Red Riding Hood’s Trials and Tribulations, in: The Lion and the Unicorn 7./8 (1983-1984), pp. 78-109.

[3] See, for example, Bradley Deane’s exploration of perpetual boyhood in British imperial stories across the turn of the twentieth century, in which he argues that “enduring boyishness” supported the conservative displacement of earlier liberal narratives of progress with “a vision of permanent dominion and endless competition.” Idem, Imperial Boyhood: Piracy and the Play Ethic, in: Victorian Studies 53.4 (2011), pp. 689-714, here p. 691, online: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/eng_facpubs/5/ [06.10.2025]. Analyzing another linguistic tradition of that later era, Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg shows how The Adventures of Pinocchio (Carlo Collodi, 1883) played a part in the construction of Italian subjectivity through addressing an imagined “crisis of paternal, masculine performativity.” Idem, The Pinocchio Effect: On Making Italians, 1860-1920, Chicago 2007, p. 4. As a third example, see Penny Brown’s discussion of gender norm reinforcement through fin-de-siècle adventure and domestic fiction for young French readers. Idem, A Critical History of French Children’s Literature, vol. 2, 1830-Present, New York 2008.

[4] Portions of this section were adapted from Emily C. Bruce, Children’s Book Publishing in Europe: A Historical Approach, in: Claudia Nelson/Elisabeth Wesseling/Andrea Mei-Ying Wu (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Children’s Literature and Culture, New York 2023, pp. 441-453, online https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=history [06.10.2025].

[5] Rob Banham, The Industrialization of the Book 1800-1970, in: Jonathan Rose/Simon Eliot (eds.), A Companion to the History of the Book, Hoboken 2019, pp. 454-456, here p. 466.

[6] Lotte Hellinga, The Gutenberg Revolutions, in: Rose/Eliot (eds.), History of the Book, p. 384.

[7] Johann Amos Comenius, Orbis Sensualium Pictus, Nürnberg 1658.

[8] Andrea Immel, Children’s Books and Constructions of Childhood, in: M. O. Grenby/Andrea Immel (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Children’s Literature, Cambridge 2009, pp. 19-34, here p. 30.

[9] Katie Trumpener, Picture-Book Worlds and Ways of Seeing, in: Grenby/Immel (eds.), Children’s Literature, pp. 55-75, here p. 57.

[10] See Gerhard Michel, Die Bedeutung des “Orbis Sensualium Pictus” für Schulbücher im Kontext der Geschichte der Schule, in: Paedagogica Historica 38.2 (1992), pp. 235–251; Karen Coats, Poetics and Pedagogy, in: Nelson/Wesseling/Wu (eds.), Routledge Companion to Children’s Literature, pp. 21-32; Giorgia Grilli, Nonfiction, in: Nelson/Wesseling/Wu (eds.), Routledge Companion to Children’s Literature, pp. 153-163.

[11] Robert A. Dent, John Amos Comenius: Inciting the Millennium through Educational Reform, in: Religions 12.11 (2021), pp. 1-14, online https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/12/11/1012 [06.10.2025].

[12] Margaret R. Higonnet, Travel as Construction of Self and Nation, in: Emer O’Sullivan/Andrea Immel (eds.), Imagining Sameness and Difference in Children’s Literature: From the Enlightenment to the Present Day, Basingstoke 2017, pp. 244-245.

[13] Literacy rates were also on the rise in this era. The most reliable literacy measurements come from regional studies; national averages conflate differences emerging from legal regimes, urbanization, confessions, class, and gender. In East Prussia, one of the poorest areas in the German lands, the proportion of peasants able to sign their names at the time of marriage grew from ten percent in 1750 to forty percent in 1800. Rolf Engelsing, Analphabetentum und Lektüre: Zur Sozialgeschichte des Lesens in Deutschland zwischen feudaler und industrieller Gesellschaft, Stuttgart 1973, p. 62. By the 1840s, fewer than ten percent of all Prussian men were recorded as illiterate. David Vincent, The Progress of Literacy, in: Victorian Studies 45.3 (2003), pp. 405-431, figures 2 and 3.

[14] Jeffrey Freedman, Books Without Borders in Enlightenment Europe: French Cosmopolitanism and German Literary Markets, Philadelphia 2012, pp. 15-62.

[15] Rietje van Vliet, Print and Public in Europe 1600-1800, in: Eliot/Rose (eds.), History of the Book, p. 426.

[16] Helen Fronius, Women and Literature in the Goethe Era 1770-1820: Determined Dilettantes, Clarendon 2007, pp. 140-141.

[17] “Wir fangen an einen großen Reichtum an Schriften für die Jugend zu bekommen, und diese gehört nicht zu den schlechtern unter denselben. Allenthalben zeigt sich gesunder Verstand; der Vortrag ist sehr fasslich und den Fähigkeiten der Jugend angemessen und dann findet die junge Seele hier lauter Materien, wodurch sie zur Gottesfurcht und zur Menschenliebe erweckt werden muß, wenn sie anders gute Gedanken und Empfindungen anzunehmen fähig ist.” Allgemeine Deutsche Bibliothek 26 (1775), p. 248; see also Pamela E. Selwyn, Everyday Life in the German Book Trade: Friedrich Nicolai as Bookseller and Publisher in the Age of Enlightenment, Philadelphia 2021.

[18] Emily C. Bruce, Revolutions at Home: The Origin of Modern Childhood and the German Middle Class, Amherst 2021, p. 15.

[19] Banham, Industrialization of the Book ; Hellinga, The Gutenberg Revolutions, p. 385.

[20] Penny Brown, Capturing (and Captivating) Childhood: The Role of Illustrations in Eighteenth-Century Children’s Books in Britain and France, in: Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 31.3 (2008), pp. 419-449.

[21] Bruce, Revolutions at Home, pp. 175-176.

[22] Jonathan Sheehan, The Enlightenment Bible: Translation, Scholarship, Culture, Princeton 2005, pp. 131-132.

[23] For a range of examples crossing the continent, see Richard Apgar, Taming Travel and Disciplining Reason: Enlightenment and Pedagogy in the Work of Joachim Heinrich Campe, PhD Dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2008, online https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/xp68kh134 [06.10.2025]; Arianne Baggerman/Rudolf Dekker, Child of the Enlightenment: Revolutionary Europe Reflected in a Boyhood Diary, Leiden 2009; Nadine Bérenguier, Conduct Books for Girls in Enlightenment France, Farnham 2011; Feike Dietz, Lettering Young Readers in the Dutch Enlightenment: Literacy, Agency and Progress in Eighteenth-Century Children’s Books, Berlin 2021; Jennifer J. Popiel, Rousseau’s Daughters: Domesticity, Education, and Autonomy in Modern France, Durham 2008.

[24] Carol Poster/Linda C. Mitchell (eds.), Letter-Writing Manuals and Instruction from Antiquity to the Present: Historical and Bibliographic Studies, Columbia 2007; Bruce, Revolutions at Home, p. 48.

[25] Bruce, Revolutions at Home, pp. 89-90.

[26] Ruth-Ellen Joeres, The German Enlightenment (1720-1790), in: Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly (ed.), The Cambridge History of German Literature, Cambridge 2008, pp. 197-198; Hubert Göbels, Zeitschriften für die deutsche Jugend: eine Chronographie 1772-1960, Dortmund 1986.

[27] François Genton/Sebastian Schmiedeler/Tom Zille (eds.), Christian Felix Weißes Werk im europäischen Kontext. Kinder- und Jugendliteratur, Kulturtransfer und populäre Aufklärung, Stuttgart, forthcoming.

[28] “Ich will die Unterhaltung meiner Kinder wöchentlich, statt jenes Wochenblattes, das Euch so sehr am Herzen lag, Euch mittheilen. Vielleicht ist sie nicht für Euch so angenehm, als jenes; aber ich gebe Euch so viel, als ich habe: Die Begierde, womit Ihr es bey dem Verleger abholen und lesen werdet, wird mich bald überzeugen, ob ich diese kleinen Familienunterhaltungen fortsetzen, oder abbrechen soll.” Christian Felix Weiße, Der Kinderfreund I, no. 1, Leipzig 1776, p. 7.

[29] Christian Felix Weiße, Der Kinderfreund: Ein Wochenblatt für Kinder, Leipzig: 1775-1782; Luise Hölder, Kleine Weltgeschichte von den ältesten bis auf die neuesten Zeiten, in anziehenden, regelmäßig fortlaufenden Erzählungen für Kinder von 6 bis 12 Jahren, Nürnberg 1823; Heinrich Hoffmann, Der Struwwelpeter [Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder], Frankfurt am Main 1845.

[30] On affectionate relationships between German men in the late Enlightenment, see Suzanne L. Marchand, Becoming Greek. Johann Joachim Winckelmann is Murdered in Trieste, in: David E. Wellbery et al. (eds.), A New History of German Literature, Cambridge, Massachusetts 2005, pp. 376-381. See also Brian Joseph Martin, Napoleonic Friendship: Military Fraternity, Intimacy, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century France, Durham 2011; Richard Godbeer, The Overflowing of Friendship: Love between Men and the Creation of the American Republic, Baltimore 2009.

[31] Nina Rattner Gelbart, Adjusting the Lens: Locating Early Modern Women of Science, in: Early Modern Women 11.1 (2016), pp. 116-127.

[32] See Angelika Linke’s discussion of how the great illustrator Daniel Chodowiecki visualized the bourgeois ideal of “naturalness” through the body. Idem, Sprachkultur und Bürgertum: Zur Mentalitätsgeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts, Stuttgart 1996, p. 77ff. On Chodowiecki’s illustrations for children, see Bettina Hürlimann, Three Centuries of Children’s Books in Europe, trans. and ed. Brian W. Alderson, Cleveland 1968, pp. 132-133.

[33] Pamela Gay-White/Adrianne Wadewitz, Introduction: Performing the Didactic, in: The Lion and the Unicorn 33.2 (2009), pp. v-vi.

[34] Ann Taylor Allen, “Let Us Live with Our Children”: Kindergarten Movements in Germany and the United States, 1840-1914, in: History of Education Quarterly 28.1 (1988), pp. 23-48.

[35] See Ann Taylor Allen, Feminism and Motherhood in Western Europe, 1890-1970: The Maternal Dilemma, Basingstoke 2005.

[36] Hölder, Kleine Weltgeschichte, p. 14.

[37] Ibid., pp. 12-18.

[38] Ibid., p. 13.

[39] Ibid., p. 223.

[40] Ibid., p. 225.

[41] Thank you to Christina Benninghaus for this insight.

[42] See Gianna Pomata’s discussion of how exemplary women appeared and disappeared in European historiography. Idem, History, Particular and Universal: On Reading Some Recent Women’s History Textbooks, in: Feminist Studies 19.1 (1993), pp. 7-50.

[43] F. J. Harvey Darton, Children’s Books in England: Five Centuries of Social Life, Cambridge 1932, p. 250.

[44] Twenty-six German editions of Der Struwwelpeter appeared within the first fifteen years of its publication, selling tens of thousands of copies. Walter Sauer, A Classic Is Born: The ‘Childhood’ of ‘Struwwelpeter’, in: The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 97.2 (2003), pp. 215-263, here p. 245. Today it is available in more than a hundred languages. Idem (ed.), Der polyglotte Struwwelpeter, by Heinrich Hoffmann, Neckarsteinach 2008, p. 73.

[45] Sauer, Classic, pp. 240-241.

[46] Ibid., pp. 221-224.

[47] Ibid., p. 236.

[48] Translation anonymous, quoted from: https://www.babelmatrix.org/works/de/Hoffmann%2C_Heinrich-1809/Die_gar_traurige_Geschichte_mit_dem_Feuerzeug/en/40213-The_Dreadful_Story_of_Harriet_and_the_Matches [06.10.2025].

[49] “Ich zünde mir ein Hölzchen an, wie’s oft die Mutter hat getan.” Hoffmann, p. 6. Thank you again to Christina Benninghaus for this observation.

[50] The phrase “qualities of mind” comes from Nancy Armstrong in her discussion of eighteenth-century gender ideology. Idem, Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel, Oxford 1987, p. 4.

[51] Weiße, vol. I, no. 1, pp. 9-13.

[52] “Es gibt Personen, welche der Meinung sind, es sei unnötig, daß Kinder von sechs bis zwölf Jahren, etwas von der Weltgeschichte erfahren. Dagegen aber nimmt man keinen Anstand, ihnen Märchen oder Geschichten von artigen oder unartigen Kindern zu erzählen oder lesen zu lassen, wodurch sie oft unrichtige Begriffe fassen, und bekannt mit Fehlern werden, die sie zuvor nicht kannten. – Warum also nicht lieber ihnen wahre Begebenheiten erzählen, die sie bei einer guten Erziehung, ja doch einmal wissen und lernen müssen?” Hölder, Kleine Weltgeschichte, pp. iii-iv.

[53] For one account of how European historians particularly have debated this chronology (and the concept of “separate spheres” itself), see Alexandra Shepard/Garthine Walker, Gender, Change and Periodisation, in: Shepard/Walker (eds.), Gender and Change: Agency, Chronology and Periodisation, Hoboken 2009, pp. 1-12.

This article is part of the theme dossier “Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive,” edited by Christina Benninhaus and Mary Jo Maynes.

Theme Dossier: Putting Images to Work – Gender and the Visual Archive

Zitation

Emily C. Bruce, Ambiguous Representations of Gender in Late Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century Illustrations in German Children’s Literature, in: Visual History, 13.10.2025, https://visual-history.de/2025/10/13/bruce-ambiguous-representations-of-gender-in-late-eighteenth-and-early-nineteenth-century-illustrations-in-german-childrens-literature/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2952

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Eine Nutzung ist für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in unveränderter Form unter Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de