Escaping the War Horror:

“Tourist” Photographs of Thessaloniki under the German Occupation (1941-1944)

Introduction

Byron Metos is a Greek collector based in Thessaloniki, whose interest focuses on war photography and more specifically on the photography of the two World Wars in Greece. Part of his collection is titled Balkan und Griechenland (Balkans and Greece) and comprises photographs taken mostly by German soldiers and officers, though also including those by itinerant photographers, during the years of the Nazi Occupation in the Balkans, which have originated from photo albums of German soldiers.

During the postwar era, these were acquired by an officer who had served in Greece as a member of the Health Service of the German army. A pensioner in a small town in what was then West Germany, many years after the War, he decided to trace his own route through the war by adding the photographs of his fellow soldiers to his own photographic souvenirs – a process he pursued until the end of his life, spending much time in tracing his former fellow soldiers or their relatives. After his death, the collection passed to his daughter, who, a year later, sold the section relating to Greece, namely almost three thousand (3,000) photographs, to Byron Metos, expressing, however, her wish to retain her family’s anonymity.

The following paper focuses on the part of the Metos Collection that refers to Thessaloniki. Roughly numbering more than 800 prints, this particular part of the collection formed the subject of an exhibition organized in February 2016 at the Museum of Byzantine Culture.[1] The focus of the present paper will be on photos of the “tourist destination” Thessaloniki, as demonstrated through the collection’s miscellaneous photographic material.

What a “tourist” image means is best illustrated by a tourist guide that was specially published for the Wehrmacht troops in the city and is also in the Metos Collection. Containing photographic views of Thessaloniki’s must-sees, the illustrated tourist guide will be examined in comparison to a personal photo album, which is fully preserved in the Metos Collection and formerly belonged to an anonymous German officer who served in Thessaloniki.

Highlighting the relation created between the photographs reproduced in the illustrated tourist guide and those of the personal photo album, the paper attempts to unravel the role of official photography in the production of amateur images. At the same time, we will show an escapist dimension of Nazi propaganda, summarized, as Rolf Sachsse argues, in the attempt to educate the gaze of the German soldiers to “look away”[2] from the horrors of war and the atrocities committed.

The photographic image of Nazi-occupied Thessaloniki: The Byron Metos Collection

Among the richest private collections of photographs of the Occupation period, the Byron Metos Collection is of great interest because it documents a period in the photographic history of Thessaloniki that until recently was considered to be the least photographed. Although there was no specific legal framework prohibiting photography completely,[3] taking photographs was quite difficult for a number of reasons. In areas controlled by the military, photography was only allowed for reporters operating within the PKs (Propaganda Companies).[4] Moreover, the German procedure of controlling photographic production was quite harsh; many shots were censored by the Nazis, even at the slightest hint of disclosing classified information.[5] Specially authorized photo labs bearing the sign “Zugelassen für Deutsche Wehrmacht” (“Approved for the German army”) were charged with developing the amateur photographs taken by German soldiers.[6]

On a second level it was quite difficult to find photographic materials. Before leaving Greece the Allied troops had destroyed the Kodak facilities, so that the Germans would not have access to the company’s materials. Hence, the main concern of the Greek professional photographers who continued to work in occupied Greece was to secure the supply of photographic paper and chemicals. According to the photography historian Alkis Xanthakis, a source of supply was the German soldiers themselves, who traded the materials of German companies, mostly of Agfa.[7]

We are not sure whether the collection has been preserved in its entirety or whether several photographs were removed from it, most probably by the officer’s daughter, in order not to have them presented publicly. The apparently fragmentary character of the collection can be explained by the fact that the collection does not consist of the photographic souvenirs of a single Nazi soldier, but of numerous ones. Among all else, this can be indicated by the variety of cities in which the development of the photos took place, whose names are printed on the back.

The collection comprises a few samples of the photographic activities of the propaganda companies, namely the German Propagandakompanie (PK) of the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS, which were headed by the Ministry of Propaganda (RMVP) and constituted the primary method of mass communication of the “Third Reich”.[8] The photographs, namely three large prints in 13 x 18 cm format, were taken during the first days of the German Occupation by the Nazi army in Thessaloniki in early April 1941. Notably taken by members of the PK 690 unit, which was active in Greece,[9] they portray prisoners-of-war lying in the area of the city’s port (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: “Greek captive soldiers waiting for their departure, 14.4.1941”. An official German Propaganda Company photo, taken by Ernst Grunwald Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

One photo has a special paper tag on the back with the name of the PK photographer on it (Baier), together with the information that this particular shot has gone through the censorship process and been accepted for publication (Fr.O.K.W.). On two other pictures, there are hand-written captions and stamps with the PK photographer’s name (Ernst Grunwald and the indication that the photograph had not passed the censorship process. There are several errors in the captions, because in one of these photos the soldiers are Serbs and not Greeks, as the caption indicates. Press photographs like these used to be published in propaganda magazines such as “Signal” or “Adler”, whose versions appeared in various issues and languages.[10]

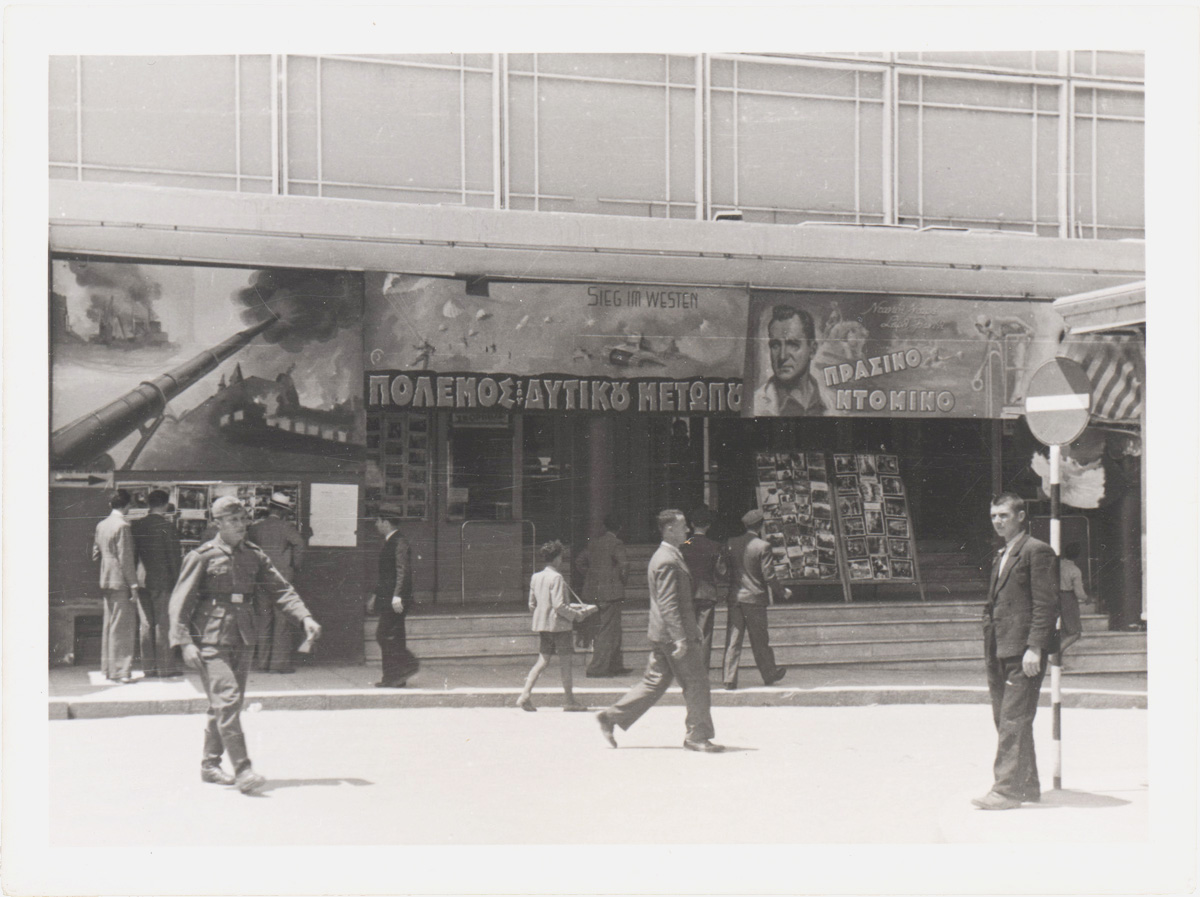

Apart from these very few verified samples of the photographic activity of the Propaganda-Kompanien, the majority of the photographs in the Metos Collection could be characterized as amateur photos. However, some can be assigned to the “buffer zone” based on their status: although they were taken by official PK photographers, they took the photos on their own “private” initiative, which Petra Bopp called “semi-private”.[11] In the samples in the Metos Collection, there are photographs that often document scenes of everyday life in the German-occupied areas. An example of this “semi-private” type of activity can be traced in a photograph of the façade of the Athenian Kronos cinema (Figure 2).[12]

Fig. 2: The Kronos cinema in Athens. The photograph was taken by PK Ernst Grunwald. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

Both the photograph’s sharpness and the viewpoint reveal a professional shot, a fact that is attested by a stamp on the back bearing the name of Ernst Grunwald, lacking any other supplementary information. This type of photograph should be associated with the “illegal” activity of the PK photographers, who, as Rolf Sachsse notes,[13] upon transfer to Berlin after a two or three month period of deployment at the front were able to smuggle back their pictures, with a few tricks, for their own use. As proved by the numerous postwar prints the Metos Collection provides us with, the diffusion of these semi-private photographs should also be linked to the postwar activity of the veterans organizations of the propaganda troops, among which “Wildente” (The Wild Duck) occupies a prominent position.[14] According to Daniel Uziel, the material produced during the war by the propaganda companies was used after the war with apologetic intent to “clean up” the Wehrmacht’s public image in postwar German society.[15]

As mentioned, apart from PK activity, the Byron Metos Collection is mostly composed of amateur photographs. Several photographic genres are represented among the collection, such as amateur snapshots depicting the soldiers’ lives in camp and other military activities, such as burial scenes from the Germany cemetery or others from the requisitioned Papafeion Orphanage, which at the time hosted the German Military Hospital. Among them, three are of particular interest because they document a military marriage by proxy (Ferntrauung) (Figure 3), a practice established at the beginning of the war to enable long-distance marriage between soldiers and their brides at home.[16]

Fig. 3. Proxy wedding ceremony (Ferntrauung) at the German Army Hospital (Papafeio Orphanage), November 1943. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

The majority of the photographs, though, show the city’s monuments or popular places; portraits of German soldiers taken by Greek itinerant photographers in front of local landmarks such as the White Tower (the 15th century Ottoman-built fortification tower which became the symbol of Thessaloniki) or the waterfront; everyday scenes such as handball matches and entertainment activities; or even postcards of soldiers sent to their families in Germany, while in some of them photo montage was used to reunite a couple “metaphorically” (Figure 4). These postcards are of significant interest because of the text they preserve on the back side, which give us further information as well as a personal perspective on the soldiers’ everyday life in a city under occupation.

Fig. 4. Post-card. “My soul belongs to you. Souvenir of Thessaloniki, 1943”. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

Kleiner Spaziergang durch Saloniki: German invaders and wartime tourism

This miscellaneous photographic material portrays an image of Thessaloniki as a city that is a “tourist destination”, a place where, at least for the soldiers pictured, everyday life was not affected by the atrocities of war and the Nazi crimes against humanity. Apart from a couple of photographs showing the remnants of the former Jewish cemetery of Thessaloniki, destroyed by the Nazis in 1942[17] (Figure 5), and one or two views of the Hirsch Jewish ghetto situated in the area of the train station, Byron Metos’ collection does not directly address aspects of the Holocaust in Thessaloniki, the historical “mother of Israel”, where more than 90% of its nearly 50,000 Jews were murdered in concentration camps[18] Other “painful” subjects are not depicted either, such as the Great Famine in 1941-42, during which the local population suffered from starvation as the Axis Powers initiated a policy of large-scale plunder.[19]

Fig. 5. The Jewish cemetery after its destruction in December 1942. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

The collection’s overall touristic and unobtrusive character could be partly attributed to postwar censorship: in their attempt to dissociate themselves from the perpetrators, the soldiers’ families occasionally removed photographs from private albums and collections.[20] However, we believe that all this photographic production is indicative of a more general discourse dominant among the German troops, which linked the experience of being a soldier to that of being a tourist. Aiming to contribute to sustaining the war effort, the German army exploited touristic language. Historian Kristin Semmens quotes the Wehrmacht High Command, according to which photo albums provided a “perfect opportunity” for soldiers to compose a souvenir, a lasting memory of their “special war experiences”.[21]

Over the last two decades, several studies have accentuated the relationship between warfare and tourism during World War II.[22] Hence, German organizations such as the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF, German Labor Front) and its sub-organization Kraft durch Freude (KdF, Strength through Joy), together with a special unit of the Wehrmacht, organized trips for Germans in France.[23] From the time the National Socialists came to power, the Kraft durch Freude organization provided the giant framework for all leisure activities and organized low cost cultural events, factory beautification campaigns through the “Schönheit der Arbeit” (Beauty of Labor) program,[24] sports, and, especially, mass tourism. Although the KdF was forced to curtail its organized tourism program during the war, the organization’s civilian and troop entertainment became an integral part of the German war effort.[25]

Formally known as “Truppenbetreuung” (Caring for the Troops), the troop entertainment program entailed the collaboration of several organizations such as the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, the Reichskulturkammer (RKK), the Kraft durch Freude (KdF) and the Propaganda Department of the Wehrmacht (OKW/WPr).[26] The program exemplified Goebbels’ belief that satisfying the recreational needs of the troops would strengthen their fighting spirit, and would also contribute to the cultivation of the cultural superiority appropriate to a master race.[27]

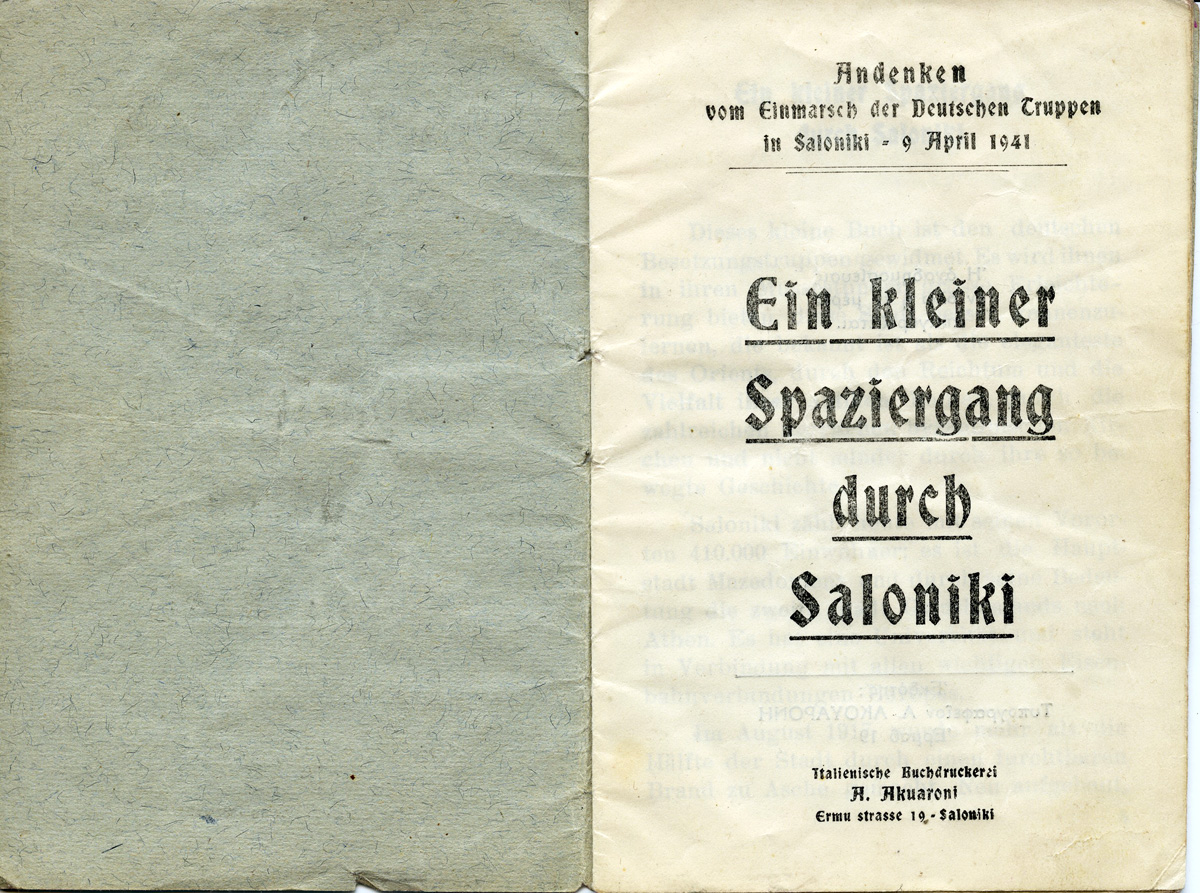

Practices already known from the First World War, such as the publication of tourist guides specifically produced for soldiers, were heavily exploited by the Nazi regime.[28] It is within this framework that the illustrated tourist guide of Thessaloniki should be examined, which was specially published for the Wehrmacht troops in the city and which is also contained in the Metos Collection. Titled Kleiner Spaziergang durch Saloniki (A short walk around Saloniki), the guide was published by A. Aquarone, a local printer of Italian descent. As stated by the subtitle itself (Andenken vom Einmarsch der Deutschen Truppen in Saloniki – Memories of the German troops’ invasion of Thessaloniki), the booklet intended to function as a souvenir of the German troops’ invasion of the city on April 9th 1941 (Figure 6).

Fig. 6: “A short walk around Thessaloniki.” Illustrated tourist guide of Thessaloniki specially published for the Wehrmacht troops in the city. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

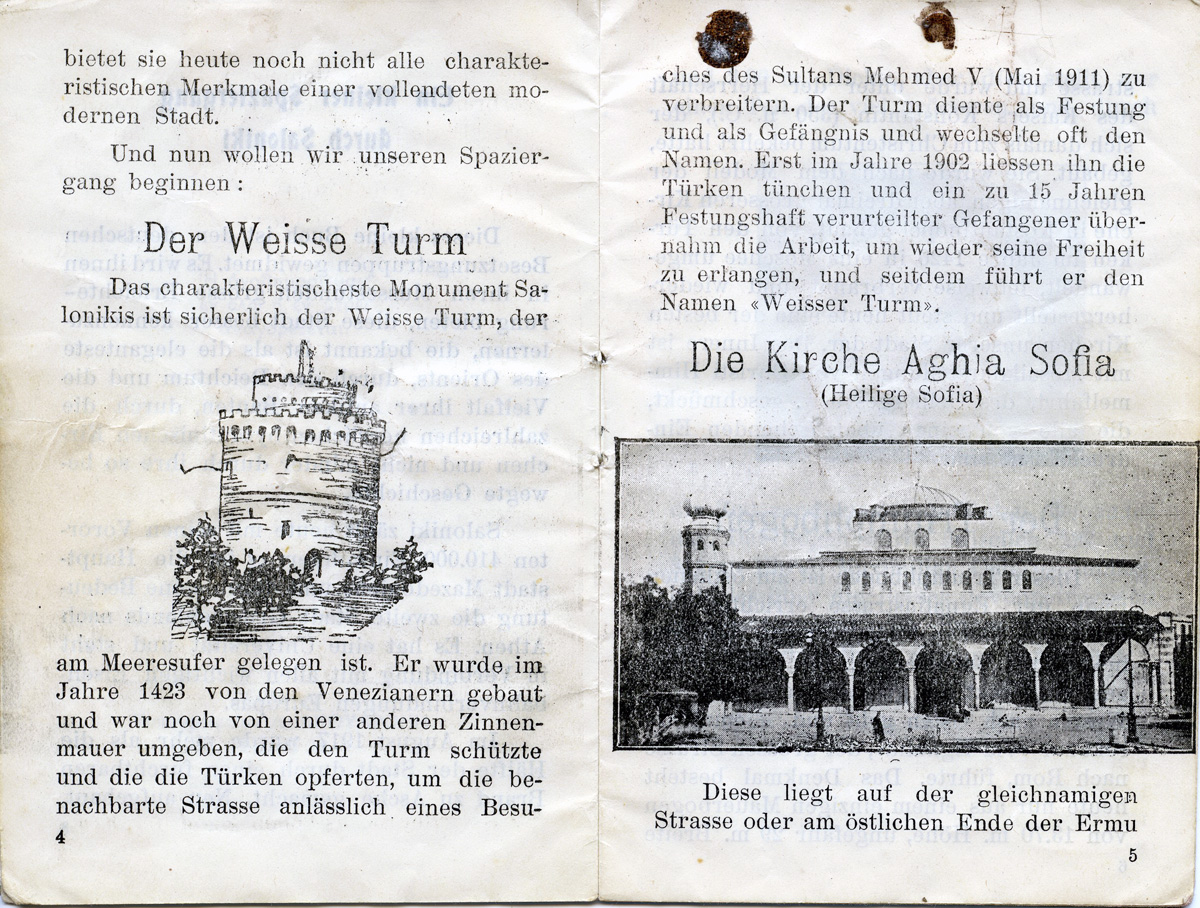

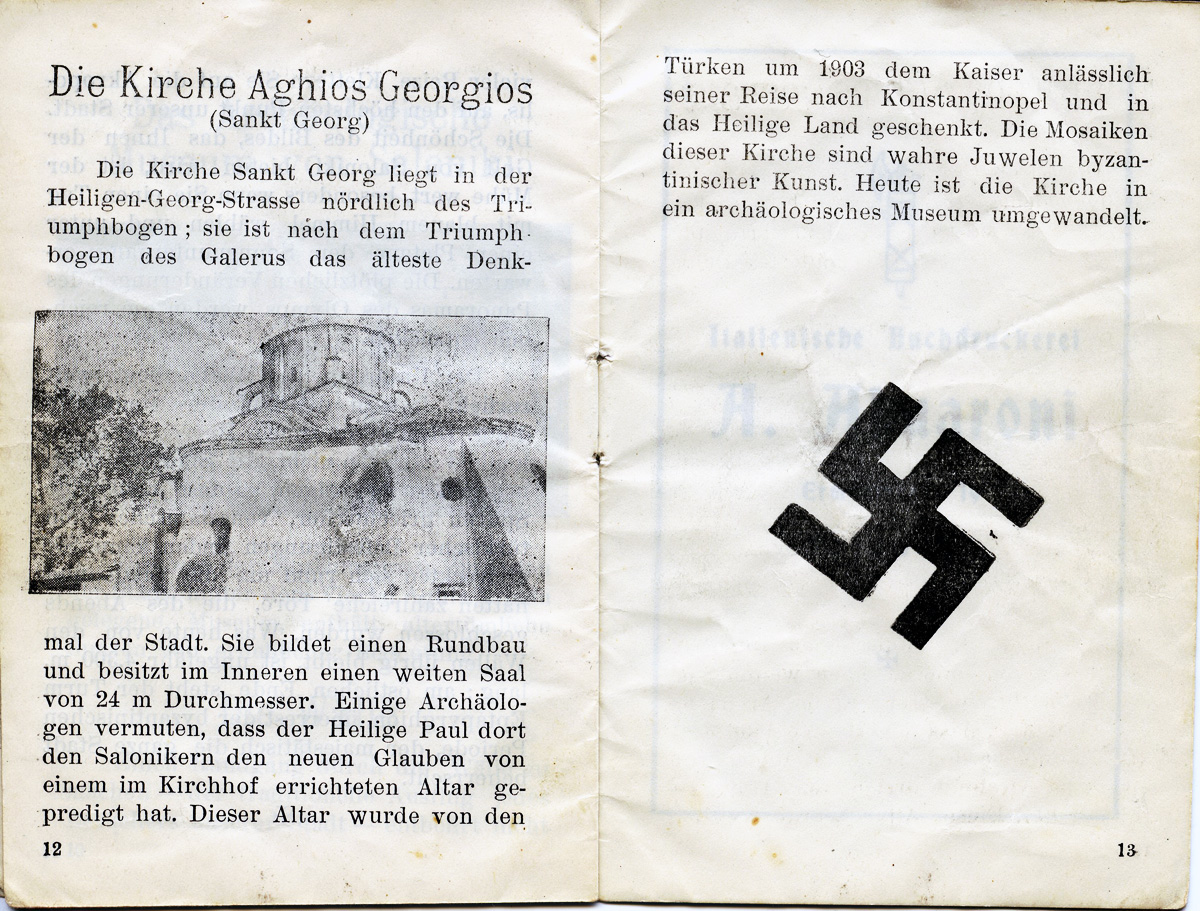

The booklet is illustrated and features a short introduction about the demographic development of the city and its recent history. A special mention is made of the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 that destroyed two-thirds of the city. The rest of the guide contains short entries on the main sights of Thessaloniki: the White Tower, the city’s landmark; the Church of Saint Sophia; Galerius’ Triumphal Arch; the Church of Saint Demetrius; the Archeological Museum, which was housed at the time in Yeni Cami, a former mosque; the Byzantine Walls of the city and the Church of Saint George, namely the Roman Rotunda (Figure 7).

Fig. 7: White Tower and the Church of Saint Sophia. Pages from the “A short walk around Thessaloniki”. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

Most of the entries are illustrated with photographs. Exceptions to this are the entries for the White Tower, which is presented in a sketch, and an icon of Saint Demetrius. Additionally, it should be noted that for the illustration of the church of Saint George, a photograph of the church of Profitis Elias was mistakenly used.

In Greece, research has revealed that tourist literature for German soldiers was associated with the activities of the Wehrmacht’s “Kunstschutz” in Greece, a special military service for the protection of art.[29] From April 1941 to July 1942 the organization was headed by Hans-Ulrich von Schoenebeck, an archeologist active in Thessaloniki during the restoration works implemented by the German Archaeological Institute of Berlin at the Triumphal Arch of Galerius and during the excavations carried out at the city’s Hippodrome.[30] Under the title “Merkblätter für den deutschen Soldaten an den geschichtlichen Stätten Griechenlands” (Notes on the Historical Sites of Greece for the German Soldier[31], a total of 466,200 copies were published, of which only very few are preserved and which are not available in a complete series.[32] An eight-page leaflet about Thessaloniki was written by Schoenebeck himself, of which 35,000 copies were published in three editions.[33] Schoenebeck, in one of his letters to archaeology professor Andreas Rumpf, describes his publishing activities as head of the “Kunstschutz”:

“The project regarding the publishing of informational leaflets was realized, and since then twelve (12) leaflets have been published, which I am sending you today. Up to now 50,000 copies have been printed. The large number of German soldiers and the great demand for the leaflets are indications that the hard times and serious events of the war have created fertile ground for the development of human thought. The Wehrmacht had the initiative for the publication of a memorial volume for the German army in Greece.”[34]

As Schoenebeck mentions in his letter, official guides to Greece and to the ancient sites were also published in book form in addition to the “Kunstschutz” leaflets. The memorial volume to which he refers is entitled “Hellas: Bilder zur Kultur des Griechentums” (1943), which he wrote with the archaeologist Wilhelm Kraiker, who succeeded him as head of the “Kunstschutz” in 1942.[35] The volume is lavishly illustrated with 96 plates, reproducing photographs by famous German photographers specialized in archaeological photography. Among them are Hermann Wagner, who extensively collaborated with the Athenian branch of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) in the 1930s, and Walter Hege, whose photographic series on the Athenian Acropolis (1928), which combined modernist viewpoints and classical ideals, best illustrated the National Socialist photographic principles.[36]

“Hellas” features contributions by important German archaeologists working in Greece, as well as an introduction by Walther Wrede, director of the German Archaeological Institute in Athens since 1936, and a high-ranking Nazi, who served as the head (Landesgruppenleiter) of the Greek local branch of the foreign organization of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP).[37] In the same vein, another volume was published on the Peloponnese, in 1944,[38] with the interesting explanation on the front page of the book that it was edited by the military high command “von Soldaten für Soldaten” (by soldiers for soldiers).[39]

Comparing the “Merkblätter” text on Thessaloniki with the one of the Metos guide, one comes to the conclusion that most probably they were not written by the same author. Schoenebeck’s “Saloniki” reveals the archaeological orientation of its author, while the Metos booklet comes closer to the typical unmediated language of a Baedeker-type tourist guide.[40] Moreover, contrary to the “Merkblätter” publications of the “Kunstschutz” organization, which present limited engraved illustrations, the Thessaloniki guide is richly illustrated with photographs, with almost one for each entry.

Schoenebeck and Kraiker’s “Hellas” on the other hand, although lavishly illustrated, differs greatly in the photographs shown: taken by prominent photographers specialized in archaeological photography, such as Hermann Wagner or Walter Hege, the illustrations in “Hellas” are characterized by extraordinary sharpness, elaborate contrasts and professional shots that highlight the monument, sometimes placing the emphasis on the detail and on other occasions experimenting with unconventional viewpoints. In contrast, the Metos guide illustrations seem to adopt “ordinary” perspectives of Thessaloniki’s popular monuments, presenting the city the way tourist postcards of the era would. Both the touristic language and the illustrations in the brochure allow us to exclude them from the publication activity of the “Kunstschutz”.

However, it is still not clear which organization, institution or individual is behind the Thessaloniki short guide. Tourist literature addressed to German soldiers was served by a variety of institutions, both official entities and private publishers. Hence, in the case of Rome a 48-page travel guide titled “Blitzführer durch Rom: für deutsche Wehrmachtsangehörige” was published by the Italian Wehrmacht with the participation of the local branch of the Foreign Organization of the NSDAP in Rome (Ortsgruppe Rom der NSDAP-Auslandsorganisation).[41] In the case of Paris, on the other hand, as the historian Bertram Gordon informs us, the travel guides for ordinary German soldiers, such as the “Deutscher Soldaten-Führer durch Paris” (German Soldier’s Guide to Paris), were hastily prepared, often by local French writers working for the occupation authorities.[42] Of course, the travel guides had to be approved by the City Commander of Paris.[43]

We should assume that the Metos booklet must have been a private initiative, which, as in the Parisian case Gordon describes, certainly had the support of the German authorities. As proved by its colophon page, the Metos booklet was published by Amedeo Aquarone, a local publisher who collaborated with the German occupation regime. The Aquarone family was of Italian descent (Italienische Druckerei), while the fascist fasces symbol that appears on the last page discloses the family’s affinities with the local Fascist Party, a fact also confirmed by written sources of the era.[44] The early printing date of the tourist guide indicates that its publication was rushed, as can be seen from the mistakenly included photo of the Church of Profitis Elias, which was used to illustrate the entry for the Church of St. George (or the Roman Rotunda) (Figure 8).

Fig. 8. Church of Saint George, namely the Roman Rotunda. Pages from the “A short walk around Thessaloniki”. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

In his letter to Rumpf, Schoenebeck explains that the rapidity of publication was the primary goal he wanted to achieve, as shown by the example of the leaflet about Crete, which was written in one night and published three days after the end of hostilities. In his opinion, the quick preparation of the “Kunstschutz” leaflets contributed more to the ideals the [German] army wished to promote than the faultless publications that would have appeared after the troops had left. Therefore, errors were unavoidable in these situations,[45] as the Thessaloniki case also proves.

Despite its obvious touristic character, the Thessaloniki publication, unlike the other sightseeing literature that was addressed to German soldiers, does not contain any practical details that might be useful for a contemporary traveler, such as shops, entertainment or transportation details. According to historian Julia Torrie, though, tourist literature took several shapes under the Nazis. Hence, some of them present a more “scholarly” character and constitute “hybrid” publications which served the dual purpose of providing information about a region’s historical and geographical specificities, and being a reminder of the occupation experience for the future.[46] A short guide to the city’s monuments, but also a souvenir of the German invasion of the city, the “Andenken vom Einmarsch der Deutschen Truppen in Saloniki” (Memories of the German troops’ invasion of Thessaloniki) should be included in this hybrid category.

Moreover, photographically illustrated publications like the one in the Metos Collection should be treated as the outcome of a systematically organized propaganda, eloquently exemplifying the regime’s attempt to control the leisure time of the German soldiers. Written testimonies from this period show that the “Caring for the Troops” program was active in Thessaloniki,[47] a fact that is also evidenced by dispersed photographic material in the Metos Collection.[48]

The Metos photos also document a visit by German navy personnel to the church of Saint Demetrius and to the city walls, two of the sights proposed in the short guide. We are led to assume that these visits were realized within the framework of the Caring for the Troops, which offered specially organized guided tours to the city’s monuments. Several archaeologists and classicists seem to have served in this troop entertainment program. Hence, according to written sources, Ludger Alscher, the classical archaeologist well-known for his multi-volume postwar work “Griechische Plastik”, gave guided tours for German soldiers, first in Thessaloniki (1942) and later in Athens.[49]

The Nazi practice of controlling the leisure time of German soldiers is apparently illustrated in their amateur photo production. As Julia Torrie has correctly pointed out, the restriction to an organized tour ensured that the soldiers photographed certain sites, not others, and there seems to have been a trickle-down effect, in which soldiers independently reproduced photos they had seen in newspapers or books.[50] The remarkable uniformity of the amateur shots of Thessaloniki’s sights seems to confirm that the mechanism of guiding the photographic gaze worked successfully.

Recording the “special war experiences”: the soldier photo album of the Metos Collection

Photography had already demonstrated its crucial role in the National Socialist state regime in 1933, when the Nazis began to institute measures to organize all aspects of photography, which were summarized by the creation of the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda and the appointment of Joseph Goebbels as propaganda minister. The role that the Nazi regime ascribed to photography is disclosed in Goebbels’ opening speech at the Berlin Photo Exhibition in 1933, who argued that photography today fulfils a lofty mission to which every German should contribute by buying a camera: “In the technical field the German people were ahead of all others, and thanks to its exceptional qualities, the small camera had conquered the whole world. […] The stakes would be high in terms of popular consumer goods, and photography would also have a particularly important political role.”[51]

Germany in the 1930s was one of the leading nations in the field of photographic technology. In photochemistry, Agfa had been developing materials for color photography since 1916. In the field of photo-mechanics, Leitz had already introduced the emblematic Leica in 1925 and with it the 35mm format in still photography, a notable advance in professional equipment.[52] The statistics of cameras sold in Germany in the years before World War II prove that Goebbels’ campaign was successful; the Leica became one of the cameras used by the PK photographers.[53] The most widely used German cameras such as the Agfa Box were more affordable for amateur photographers, while fewer people could afford cameras with more sophisticated equipment like the Contax by Zeiss and the Robot. The significance given by the regime to the photographic technology of this period can easily be seen from the numerous advertisements for photographic equipment which appeared in the propaganda magazines of the “Third Reich”.

Academic research has underlined the role of the Kraft durch Freude organization in popularizing the camera.[54] A photographer took part in most of the events organized by Kraft durch Freude in order to teach Germans which pictures they should prefer as tourists, namely to construct a photographic vision and a photographic taste for the citizens of the “Third Reich”.[55] For example, in 1936 the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labor Front) set up photography courses as a stimulating, national activity to complement the leisure pursuits of German citizens. In a book written by one of the organizers of the course, the propagandic intention of amateur photography becomes clear: “[…] amateur photography should strive to be one of the main factors in the history of civilization. […] It makes it possible to leave to one’s children and grandchildren a collection of images whose influence is far greater than that of any number of speeches.”[56]

As Rolf Sachsse argues, the aim of the Nazi regime was to control the public dissemination as well as the private production of photographs in order to create positive memories of German life under National Socialism. Through these positive images, Nazi propaganda sought to educate the German people to “look away” from the terror and the atrocities of the regime.[57] Providing its citizens with happy images was fundamental to the regime because it appeased discontent and distracted people from those things they did not want to see.

Prewar practices and attitudes were radicalized in wartime. Photography soon became a medium that constructed the images of war and brought them home. It thus developed into a priority field that the Nazi regime had to control. Hence, apart from the official PK photography, the Nazi regime sought to regulate all amateur production of the German troops. In photo magazines such as Photofreund the soldiers were asked to fulfill their “unconditional duty”, that is to keep their cameras in action,[58] while a Foto-Jahr editorial movingly described the sacrifices German soldiers would have to make to acquire a camera.[59] The photos taken by amateur photographers were intended to reinforce the Wehrmacht’s efforts to improve the morale of the troops.

The role that Nazi propaganda played in the photographic production of the soldiers is best illustrated by the personal photo albums, which were highly esteemed by the regime. Shelley Baranowski quotes advice from the Wehrmacht High Command, that photo albums offer a perfect opportunity for soldiers to compose a souvenir of their “special war experiences”.[60] Long forgotten because they were produced by “German perpetrators”, but also because they were a product of marginal amateurs and without legitimation, photo albums that had been stowed away in attics for a long time accumulating dust came back into focus over time and after the death of the last members of the National Socialist Party [61]

Thus, it is only in the last few years that research has started to focus on photo albums from the war period. Of special significance is the research project organized by the Universities of Oldenburg and Jena (2004-2008) headed by the art historian Dr. Petra Bopp, which resulted in the traveling exhibition, which toured through many Central European cities titled Fremde im Visier: Foto-Alben aus dem Zweiten Weltkrieg (Strangers in Vision: photo albums from the Second World War”.[62] As Bopp’s research has shown, the arrangements and captions of the photo albums gives an indication of how war memories were subjectively constructed, meaning they show how the war was seen, not how it really was.[63]

In Greece the photo albums of soldiers from World War II have only recently aroused the interest of researchers. Of special interest is the photo album of the Austrian archaeologist August Schörgendorfer, who excavated a Minoan settlement in Apesokari in southern Crete as a member of the Wehrmacht’s Kunstschutz organization. His photo album shows his itinerary through Crete and contains photos that betray his special interests: monuments and archaeological sites, but also others showing scenes from the everyday life of Cretan villagers. Several photos must have been removed from the album, most probably during his imprisonment by the British after he was wounded on the Russian front.[64]

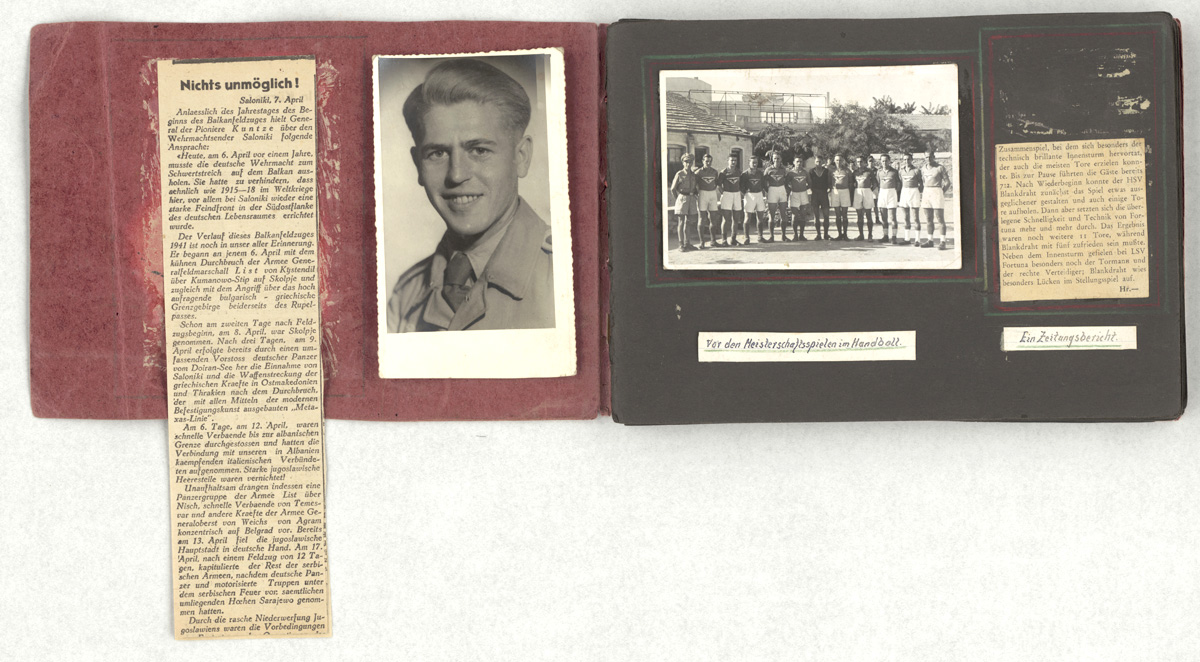

In the Metos Collection, one album from Thessaloniki is preserved in its entirety, while there are several unbound photo album pages. As in most albums, initial entry into the German forces is documented on the first page with a studio portrait of the soldier wearing his new uniform. In most cases this kind of picture radiates a sense of pride and often also euphoria. On the first page of the Metos album, next to the owner’s studio photo, there is a newspaper clipping recalling the capture of Thessaloniki by German troops (Figure 9).

Fig. 9. Page of a German soldier’s photo-album from Thessaloniki. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

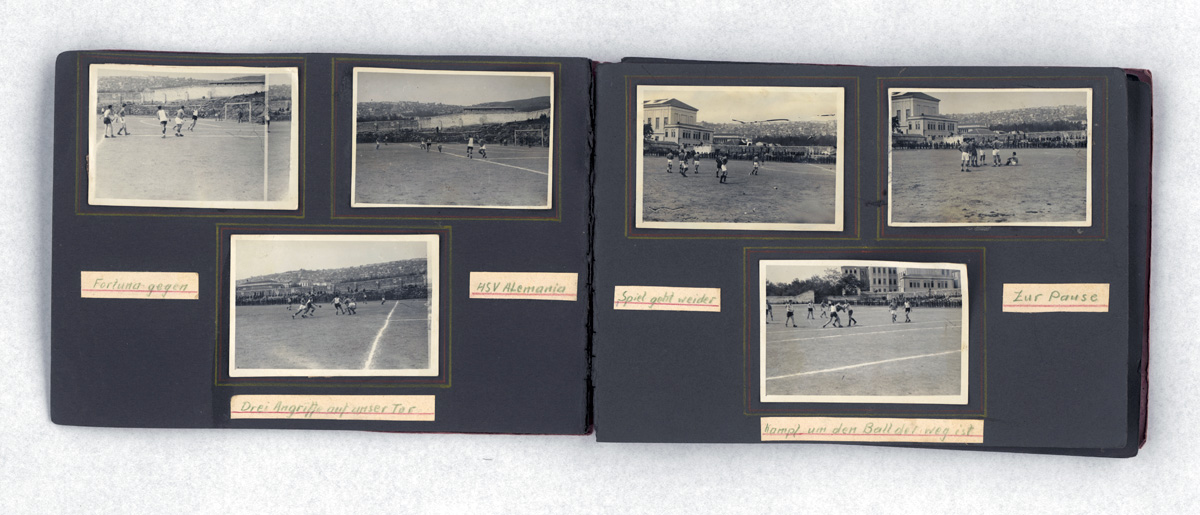

A closer look reveals traces of glue around the newspaper clipping, indicating the existence of another photograph that was removed and replaced. Unlike albums in other collections, which are arranged according to the historical course of events (front, invasion, occupation, etc.), the album in the Metos Collection starts with a handball game between two German clubs (Fortuna and Alemania) (Figure 10), which took place in 1944 in the former Heracles Stadium on the campus of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. The game is richly illustrated, while the captions narrate the game in detail.

Fig. 10. Page of a German soldier’s photo-album from Thessaloniki. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

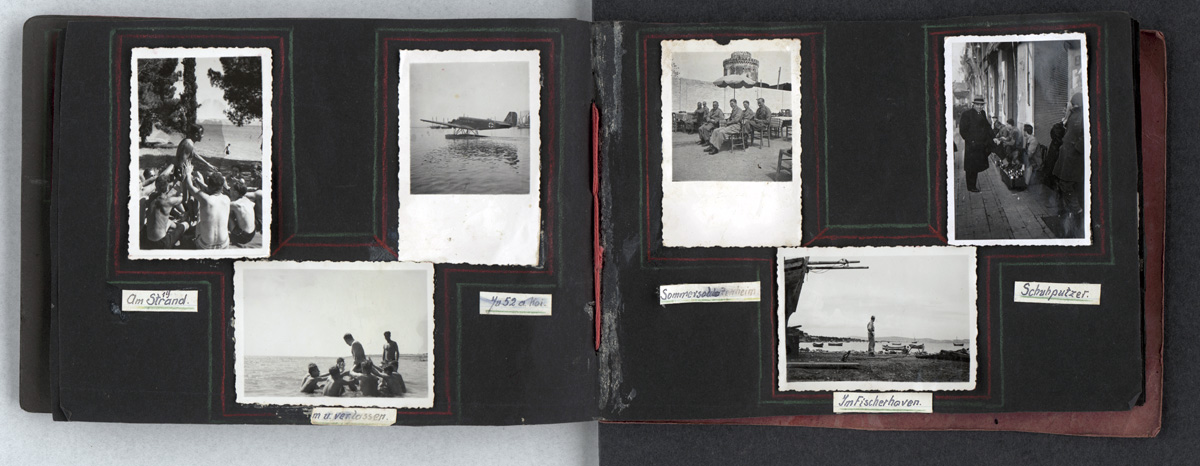

The rest of the album focuses on photos portraying camaraderie and everyday military life, recording the life in the camp, as well as tours to the city, such as leisure time at the Summer Soldatenheim, which is hosted at an open-air café next to the White Tower, or excursions to nearby beaches (Figure 11).

Fig. 11. Page of a German soldier’s photo-album from Thessaloniki. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

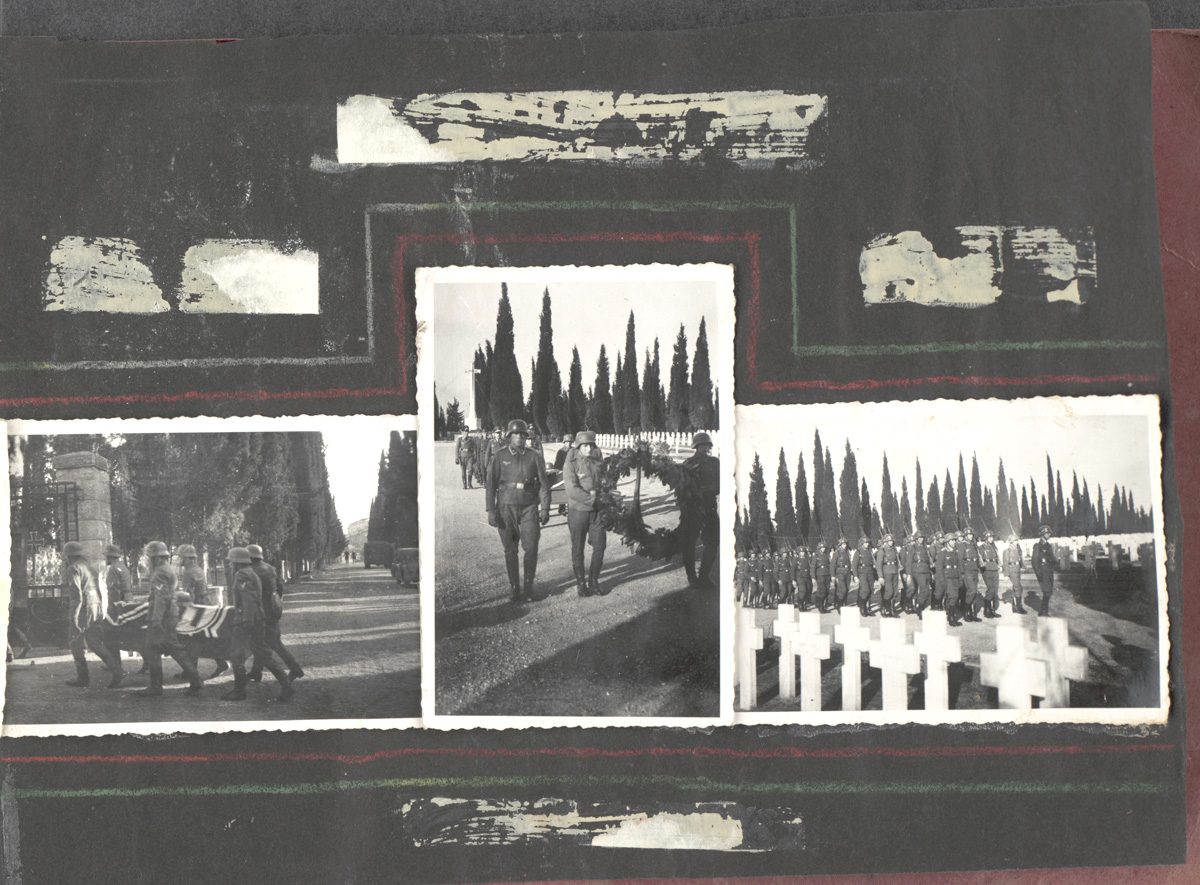

Many of the photos in the album are reminiscent of snapshots by tourists, such as the numerous romantic views of the waterfront, views of the Byzantine city walls or of the Katholikon (main church building) of the Vlatadon Monastery. The album ends with photos of soldiers’ burials in the German cemetery (Figure 12), while the last page remains blank. This abrupt end, which is the case in many albums, could, as Petra Bopp concludes, allude to the possibility of death, injury, political disillusionment or imprisonment of the owner. In contrast to the impersonal design of the first pages, the last pages of the albums usually have a more personal touch and reveal a wider range of feelings and reflect differing experiences at the end of the war.[65]

Fig. 12: Page of a German soldier’s photo-album from Thessaloniki. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

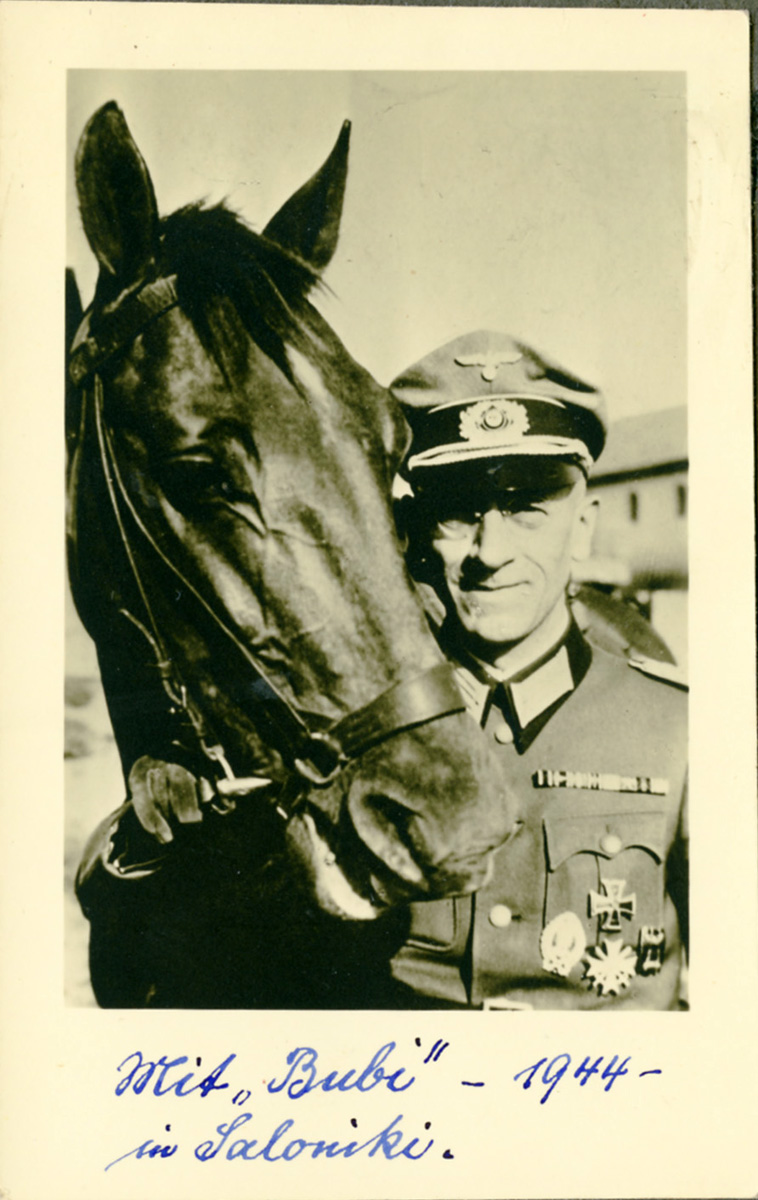

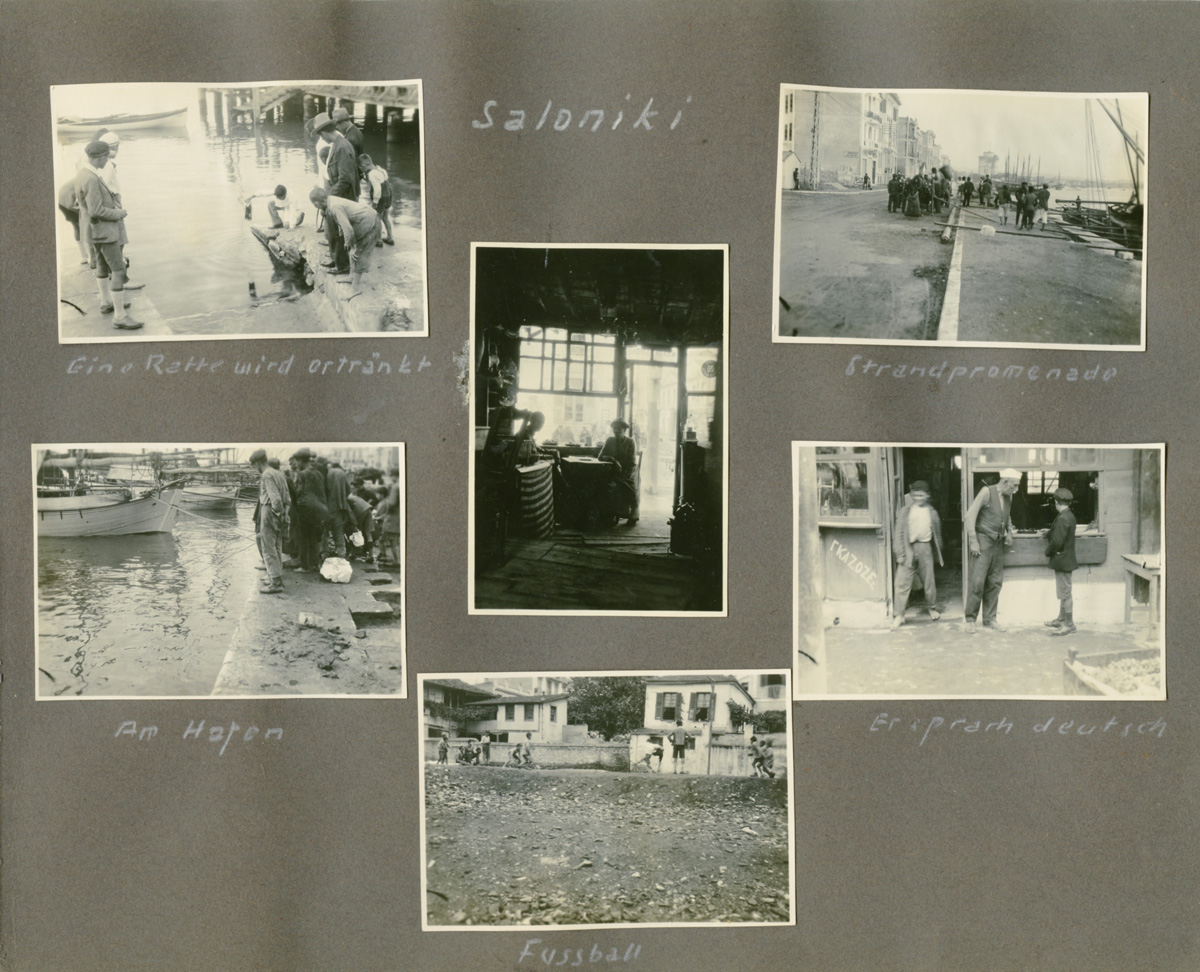

We are not sure whether the unbound pages preserved in the Metos collection come from the same photo album. A close examination of the captions helps us to distinguish three different sets of handwriting, so we can assume that they come from different photo albums. One of them must have belonged to the Wehrmacht officer posing with his favorite horse “Bubi”, which can be seen in many photos (Figure 13). The officer must have lived in the Mediterranée Hotel occupied by the Germans, as shown by a photo and its accompanying caption. (“My quartier in Thessaloniki, at the seafront,” April 1943-October 1944). Other pages of the album are dedicated to official gatherings of Wehrmacht officers, such as the one held in January 1944, or to the city’s main sights, recalling the destinations proposed by the short tourist guide: the White Tower, the Arch of Galerius and Rotunda. The remaining pages of the loose photo album show a military decoration ritual as well as scenes from daily life in occupied Thessaloniki.

Fig. 13. Page of a German soldier’s photo-album from Thessaloniki. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

Although most of the photographs in both the complete album and the unbound pages are reminiscent of tourist shots, the way occupied Thessaloniki and its people are portrayed was also influenced by racist Nazi propaganda images. Local people were pictured in all their poverty and misery to show the superiority of the Nordic master race: a young shoeshine boy, a miserable old man who distinguished himself by his ability to speak German, as the caption testifies, etc. (Figure 14).

Fig. 14: Page of a German soldier’s photo-album from Thessaloniki. Source: Byron Metos Collection © with courtesy

Conclusion: Constructing a photographic gaze for the German soldiers

Working exclusively for “Signal”, the French photographer André Zucca portrayed Nazi soldiers who handle their cameras like tourists and have a guidebook lying nearby. His photos seem to eloquently represent the entire image-making mechanism, which was typical for the amateurish photographic production of German soldiers. Together with several photographers who served in the Wehrmacht’s PK, Zucca documented the Parisian occupation by picturing soldiers buying typical French food and drinks from street vendors, visiting the Eiffel Tower or the Moulin Rouge. In their turn, occupiers who had already seen these images as propaganda pictures reproduced them themselves, just as the tourists of today inevitably photograph sunny beaches when they visit the Caribbean, or take snapshots of the Acropolis in Greece.[66]

Thessaloniki’s souvenir guidebook, specially designed for the occupying forces of the city, although most probably a private publication, should be integrated within the framework of Nazi propaganda, more specifically into their undertaking to control the leisure activities of the soldiers. The guide worked in the same way as organized tours that took place throughout the city, called “the beaten path”, a “model” itinerary for soldiers around Nazi-occupied Thessaloniki, which guaranteed that the soldiers would photograph certain sites and not others. The majority of the independent photos in the collection, as well as the ones contained in the personal photo album, echo the useful tour of the city by the occupying forces and reproduce the sights of occupied Thessaloniki with remarkable uniformity: same choices of monuments, similar focal points and angles.

The relation created between the prototype and its varied reproductions sheds light on the way the soldiers’ personal memories were “constructed”. In this light, the guidebook is exemplified as an attempt by the regime to instruct the soldiers’ photographic gaze to select positive images to be recorded. According to Sachsse’s main argument, Nazi propaganda tried, through these positive images, to educate the German people to “look away” from the terror and atrocities committed by themselves. [67] In reality, these amateur photographs transmitted and “shaped” the image of the war front among those who are left back home. Moreover, apart from appeasing discontent and distracting people from those things they did not want to see, this “happy imagery” also served another political goal, as it could maintain the soldiers’ morale and revive their energy for further victories.[68] By the time German soldiers went to the front, they were already so well-trained in this way of looking away that they were quite capable of including photos of hungry children in the same photo album with snapshots of a group of frontline comrades, urban landscapes, local monument and must-see sights.

However, unraveling the role of propaganda in the production of the soldiers’ amateur images and disclosing their escapist dimension acquires a new interpretive aspect: these images of young soldiers often enjoying themselves on the margins of war are acknowledged as disturbing, revealing their inherent ambiguity. Thus historicized, to follow Fredric Jameson’s highly acclaimed phrase,[69] they give a better insight into how the German people’s compliance with the Nazi crimes worked and where it came from. This approach is a political one that strives to maintain a clear and distinguishable distance from revisionist positions that attempt to appease the subject. This latter revisionism looks to trivialize and relativize the Nazi crimes by presenting the “human” or even sympathetic aspects of their everyday life, equating thus perpetrators and victims, rather than acknowledging the unambivalent and brutal divisions between those two parties.

[1] Iro Katsaridou/Ioannis Motsianos (eds.), On the Margins of War: Thessaloniki under the German Occupation (1941-1944) through the Photographic Collection of Byron Metos, Thessaloniki 2016.

[2] Rolf Sachsse, Die Erziehung zum Wegsehen: Fotografie im NS-Staat, Dresden 2003.

[3] Martin Rüther, Fotografieren verboten!? Möglichkeiten und Grenzen privater Fotografie im Zweiten Weltkrieg, in: Thomas Deres/Martin Rüther/Rolf Sachsse (eds.), Fotografieren verboten! Heimliche Aufnahmen von der Zerstörung Kölns, Köln 1995, pp. 63-92, see p. 67; Rolf Sachsse, “Es wird nochmals ausdrücklichst darauf hingewiesen …” Aspekte der Bildzensur im NS-Staat und im Zweiten Weltkrieg, in: Deres/Rüther/Sachsse (eds.), Fotografieren Verboten!?, pp. 11-62, see p. 12, online https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/reprint/5256 [10.05.2022].

[4] Daniel Uziel, German Propaganda Photography in the Ghettos, in: Daniel Blatman (ed.), Regards sur les ghettos = Scenes from the Ghetto, Paris 2013, p. 140.

[5] Rüther, Fotografieren verboten!?

[6] Alkis Xanthakis, Ιστορία της ελληνικής φωτογραφίας 1839-1970 [History of Greek Photography: 1839-1970] (in Greek), Athens 2008, p. 386.

[7] Xanthakis, History of Greek Photography, p. 386-7.

[8] Daniel Uziel, Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops and the Jews, in: Yad Vashem Studies 29 (2001), p. 2-4.

[9] Xanthakis, Photography and Propaganda, Vol. 2, p. 144-145.

[10] Jeremy Harwood, Hitler’s War: World War II as Portrayed by Signal, the International Nazi Propaganda Magazine, London 2014, p. 6-7

[11] Petra Bopp, Images of Violence in Wehrmacht Soldiers’ Private Photo Albums, in: Jürgen Martschukat/Silvan Niedermeier (eds.), Violence and Visibility in Modern History, New York 2013, pp. 181-197, see p. 182.

[12] The authors would like to thank Demetra Tzivopoulou for identifying the cinema façade as that of the Kronos Cinema in Athens, correcting, thus, the caption on the back, which had placed the shot in Thessaloniki. For this photograph see Katsaridou/Motsianos, On the Margins of War, p. 35.

[13] Rolf Sachsse, Fotografie als NS-Staatsdesign. Ein Medium und sein Mißbrauch durch Macht, in: Klaus Honnef/Rolf Sachsse/Karin Thomas (eds), Deutsche Fotografie: Macht eines Mediums 1870-1970, Köln 1997, pp. 118-134, see p. 131.

[14] Daniel Uziel, The Propaganda Warriors: The Wehrmacht and the Consolidation of the German Home Front, Oxford/New York 2008, pp. 357-379.

[15] Ibid, p. 341.

[16] Cornelia Essner/Edouard Conte, „Fernehe“, „Leichentrauung“ und „Totenscheidung“. Metamorphosen des Eherechts im Dritten Reich, in: Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 44 (1996), No. 2, pp. 201-227, online https://www.ifz-muenchen.de/heftarchiv/1996_2_2_essner.pdf [10.05.2022].

[17] Leon Saltiel, Dehumanizing the Dead. The Destruction of Thessaloniki’s Jewish Cemetery in the Light of New Sources, in: Yad Vashem Studies 42 (2014), No. 1, pp. 1-35.

[18] Steven B. Bowman, The Agony of Greek Jews, 1940-1945, Stanford 2009, p. 189.

[19] Mark Mazower, Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims, and Jews, 1430-1950, New York 2005, p. 393.

[20] Petra Bopp/Sandra Starke, Focus on Strangers. Photo Albums of World War II, in: Petra Bopp/Sandra Starke (eds.), Fremde im Visier – Fotoalben aus dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, Bielefeld 2009, p. 72, online https://www.fremde-im-visier.de/Fremde-im-visier-english.html [10.05.2022].

[21] Kristin Semmens, Seeing Hitler’s Germany: Tourism in the Third Reich, Houndmills 2005, p. 178.

[22] Bertram M. Gordon, Ist Gott Französisch? Germans, Tourism, and Occupied France, 1940-1944, in: Modern & Contemporary France 4 (1996), pp. 287-298; Bertram M. Gordon, Warfare and Tourism: Paris in World War II, in: Annals of Tourism Research 25 (1998), No. 3, pp. 616-638.

[23] Gordon, Warfare and Tourism, p. 618.

[24] Ulrich Prehn, Working Photos: Propaganda, Participation, and the Visual Production of Memory in Nazi Germany, in: Central European History 48 (2015), pp. 366-386, online https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/18452/24586/working-photos-propaganda-participation-and-the-visual-production-of-memory-in-nazi-germany.pdf [10.05.2022].

[25] Shelley Baranowski, Strength through Joy: Consumerism and Mass Tourism in the Third Reich, Cambridge 2007, p. 200-1.

[26] Alexander Hirt, “Die Heimat reicht der Front die Hand”: Kulturelle Truppenbetreuung im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945. Ein deutsch-englischer Vergleich, Göttingen 2009, p. 17. http://webdoc.sub.gwdg.de/diss/2009/hirt/hirt.pdf [10.05.2022]

[27] Baranowski, Strength through Joy, p. 204.

[28] Erwin Anders, Deutscher Soldaten-Führer durch Gent, Berlin 1916.

[29] Alexandra Kankeleit, Archäologische Aktivitäten in Griechenland während der deutschen Besatzungszeit, 1941-1944, Paper Lecture Berlin/Frankfurt a.M/Athen 2015/2016, p. 36-37, online https://www.academia.edu/23316327/ Archäologische_Aktivitäten_in_Griechenland_während_der_deutschen_Besatzungszeit_1941-1944 [10.05.2022].

[30] C. Steimle, Neue Erkenntnisse zum Heiligtum der ägyptischen Götter in Thessaloniki. Ein unveröffentlichtes Tagebuch des Archäologen Hans von Schoenebeck, in: AErgoMak 16 (2002), pp. 291-306, see p. 293.

[31] Merkblätter für den deutschen Soldaten an den geschichtlichen Stätten Griechenlands, Saloniki 1942.

[32] Vasilios Petrakos, Tα αρχαία της Ελλάδος κατά τον πόλεμο 1940-1944 [The Antiquities of Greece during the War 1940-1944], in: Mentor 7 (1994), No. 31, pp. 146-148.

[33] Ibid, p. 145.

[34] Hans-Ulrich Schoenebeck, Letter to Andreas Rumpf dated 4 July 1941, in: Petrakos, Antiquities of Greece, p. 118.

[35] Hans-Ulrich von Schoenebeck/Wilhelm Kraiker (eds.), Hellas: Bilder zur Kultur des Griechentums, Burg b. M. 1943.

[36] Sachsse, Fotografie als NS-Staatsdesign, p. 123-4.

[37] William John O’Keeffe, A Literary Occupation: Responses of German Writers in Service in Occupied Europe, Cork 2012, p. 60-61, online http://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/opus4/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/33047/file/OKeeffeWJ_PhD2012.pdf [10.05.2022]; Klaus Junker, Research under Dictatorship: the German Archaeological Institute 1929-1945, in: Antiquity 72 (1998), pp. 282-292, see p. 285.

[38] Der Peloponnes: Landschaft, Geschichte, Kunststätten; von Soldaten für Soldaten. Athen 1944.

[39] O’Keeffe, Literary Occupation, p. 62.

[40] Rudy Koshar, “What Ought to Be Seen”: Tourists’ Guidebooks and National Identities in Modern Germany and Europe, in: Journal of Contemporary History 33 (1998), No. 3, pp. 323-340, see p. 326.

[41] Fulvio Bianconi/NSDAP Auslands-Organisation Ortsgruppe Rom, Blitzführer durch Rom: Für Deutsche Wehrmachtsangehörige, Rom 1942.

[42] Gordon, Ist Gott Französisch?, p. 289.

[43] Deutscher Soldaten-Führer durch Paris: [Von Jean Kenoun.], Paris 1940.

[44] Julia Phillips Cohen/Sarah Abrevaya Stein (eds.), Sephardi Lives. A Documentary History, 1700-1950, Stanford 2014, p. 242-3.

[45] Petrakos, Antiquities of Greece under German Occupation, p. 123.

[46] Julia S. Torrie, “Our Rear Area Probably Lived Too Well”: Tourism and the German Occupation of France, 1940-1944, in: Journal of Tourism History 3 (2011) No. 3, pp. 309-330, here p. 310-1.

[47] Steven B. Bowman/Isaac Benmayor, The Holocaust in Salonika: Eyewitness Accounts, New York 2002, p. 134-5.

[48] A photograph from the Metos collection confirms that the confiscated building housing the Kraft durch Freude organization was located on Eleftherias Square, a notorious place where almost nine thousand (9,000) Salonican Jews were summoned by the Nazis and humiliated and beaten on the pretext that they had been registered “for work”. See Mazower, Salonika: City of Ghosts, p. 395.

[49] Uwe Hoßfeld, Hochschule im Sozialismus: Studien zur Geschichte der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena (1945-1990), Köln 2007, p. 1818. We would like to thank Prof. Kristin Semmens for highlighting Ludger Alscher’s activity in occupied Greece. Ludger Alscher, Griechische Plastik, Bd. 2.1, Berlin 1961.

[50] Torrie, Our Rear Area Probably Lived Too Well, p. 321.

[51] Speech by Reichsminister Goebbels, in: Hefte der Betriebsausstellung Druck und Reproduktion No. 1, Berlin 1933, pp. 3-6. Mentioned by Rolf Sachsse, Germany: The Third Reich, in: Jean-Claude Lemagny/André Rouillé (eds.), A History of Photography: Social and Cultural Perspectives, Cambridge 1987,pp. 150-157, here p. 150.

[52] Naomi Rosenblum, A World History of Photography, New York 1984, p. 625.

[53] Sachsse, Erziehung zum Wegsehen, p. 189.

[54] Shelley Baranowski, Radical Nationalism in an International Context: Strength through Joy and the Paradoxes of Nazi Tourism, in: John K. Walton (ed.), Histories of Tourism Representation, Identity, and Conflict, Clevedon/Buffalo 2005, pp. 125-143, here p. 138.

[55] Sachsse, Germany: The Third Reich, p. 152.

[56] Alexander de la Croix/D. Richard Lange/Max Schiel, Photographierte Familiengeschichte, Berlin 1937, p. 3. Mentioned by Sachsse, Germany: The Third Reich, p. 154.

[57] Sachsse, Erziehung zum Wegsehen, p. 73.

[58] Timm Starl, Knipser. Die Bildgeschichte der privaten Fotografie in Deutschland und Österreich von 1880 bis 1980, Munich/Berlin, 1985, p. 111.

[59] Wilhelm Schöppe, Das Foto-Jahr 1942: Taschenbuch und Ratgeber für jeden Amateur, Halle 1942.

[60] Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv Freiburg, W6/440 in: Baranowski, Radical Nationalism in an International Context, p. 138.

[61] Frances Guerin, Through Amateur Eyes: Film and Photography in Nazi Germany, Minneapolis/London 2011, p. 1.

[62] Petra Bopp/Sandra Starke, Fremde im Visier. Fotoalben aus dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, Bielefeld 2009, online http://www.fremde-im-visier.de/publikationen.html [10.05.2022].

[63] Bopp, Images of Violence in Private Photo-Albums.

[64] Georgia Flouda, Οδοιπορικό στην Κρήτη του 1941-1943: το φωτογραφικό αρχείο του Αυστριακού αρχαιολόγου August Schörgendorfer (An Itinerary to Crete 1941-1943: The Photo-Archive of the Austrian Archaeologist August Schörgendorfer) [in Greek], in: Proceedings of the Symposium “Days of 1943. Everyday Life in Occupied Crete“, 26 & 27 November 2012, Historical Museum of Crete, Heraklion, 2012, p. 60.

[65] Bopp, Images of Violence in Private Photo Albums.

[66] Torrie, Our Rear Area Probably Lived Too Well, p. 321.

[67] Sachsse, Erziehung zum Wegsehen, p. 73.

[68] Mary Elizabeth O’Brien, Nazi Cinema as Enchantment. The Politics of Entertainment in the Third Reich, Rochester, NY 2004, p. 3.

[69] Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act, 7th ed., Ithaka 1994, p. 2.

This article is part of the theme dossier: Propagandafotografie, ed. Jens Jäger

Zitation

Iro Katsaridou und Ioannis Motsianos, Escaping the War Horror: “Tourist” Photographs of Thessaloniki under the German Occupation (1941-1944), in: Visual History, 07.06.2022, https://visual-history.de/2022/06/07/katsaridou-motsianos-escaping-the-war-horror/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2394

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz Creative Commons by-nc-nd 3.0. Eine Nutzung ist für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in unveränderter Form unter Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/de/.