Recycling the Orphan Photograph: The Visual Commemoration of the Jewish Past

An unknown child, date unknown. Source: Grodzka Gate Centre – NN Theatre Lublin © courtesy of

Throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, the Holocaust brought about a widespread pillaging of Jewish possessions. Jewellery, clothes, shoes, kitchen utensils, bed sheets, furniture and entire dwellings were usurped, not only acquiring new owners but also new identities. While on the whole these utilitarian objects remained silent about their former Jewish owners, orphaned family photographs spoke volumes about the destruction of once thriving communities. Imprinted with faces that might have been known to the looters and signed with names that left no doubt as to the origins of the subjects, these images were no easy plunder. Nonetheless, many of them did survive, often buried in the attics and cellars of old houses, stashed away under floorboards or beneath window panes, forgotten for decades. Deprived of the families that had lovingly collected and preserved them, these family photographs became war orphans. As a result, the once-important personal meanings of the images became obscured and obliterated. Once discovered, in a post-Holocaust culture these orphan photographs entered a new public life, shifting away from the domestic sphere they had originally been destined to inhabit. Following World War II family photographs of European Jews have often been used in the documenting and public commemoration of the Jewish past, as seen in documentary filmmaking, museum projects and NGO work, among other arenas. Yet, in the process of being recycled, these private photographs become invested with collective values through which new visions of the past are projected and group interests promoted, making these images subject to radical reinterpretation and rereading.

Over the years a lot of scholarly attention has been paid to photographs from the Holocaust, including images from the ghettos and death camps. Equally, their subsequent dissemination and growing importance within the media culture have been subject to much debate.[1] Although some research has focused on family photographs as markers of intergenerational trauma, little has been written on how private images function in the remembrance of Europe’s decimated Jewish communities.[2] Similarly, much research on the commemoration of European Jewry has concentrated on the heritage preservation, memorial building and festival organisation, rather than the safeguarding, consuming, discarding and recycling of the visual remains of individual Jewish lives.[3] Finally, although the concept of „orphan work” is being increasingly used in film studies, there has been little application of this framework in the field of photography, with the exception of recent work on the African diaspora in Europe.[4]

The aim of this project is thus to explore the new lives of family photographs of European Jewry, both those taken before and during World War II. Drawing on case studies from Czech Republic, Germany and Poland, I look at the ways in which orphan images have been used by documentary filmmakers, artists, NGOs and museums, and examine how the involvement from the various agents affects the subsequent readings of these artefacts. Working from the premise that a photograph is not only a two-dimensional representation but also a three-dimensional object, I show how these family images are distributed, abandoned, salvaged and brought back to life, in particular within the new media cultures. The project employs the following methods: documenting ways in which photographs have been used in a variety of media; analysing life stories and narratives surrounding these images (e.g. stories by those who donated the photographs and contemporary responses to these images); conducting interviews with social actors who recycle and reinterpret these photographs (e.g. artists, museum staff, NGO activists); recording and analysing major debates in the Czech, German and Polish media.

This project is interdisciplinary in scope and straddles the fields of history, visual media and East/Central European studies. Drawing on and explicating complex narratives surrounding the disputed memories of Jewish past, this study explores how photographs evolve into battlefields of memory and acquire new meanings that match the shifting political conditions. In addition, as an examination of „orphan photography”, this project contributes to an understanding of how anonymous, abandoned and forgotten photographs get discovered and come to function within the public sphere, constituting an invitation to storytelling and inevitably, manipulation. Finally, as a comparative study of three states that have had different experiences with commemorating both the Jewish past and the Shoah, this project constitutes an important voice in the ongoing debate on the appropriation, sublimation and manipulation of the memory of World War II in post-1945 Europe and the resulting myths which shape the new European order and affect contemporary identities, at both national and supra-national levels.

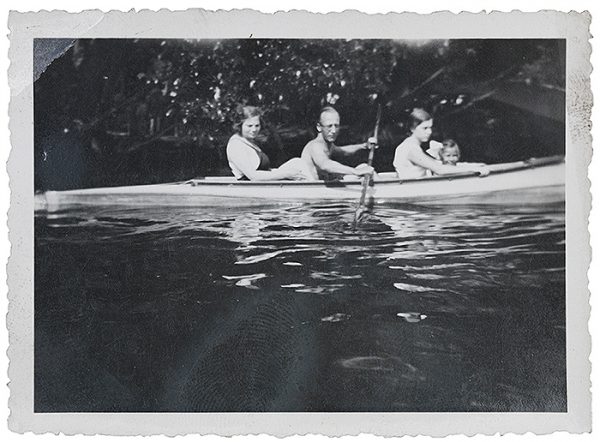

A man with two women and a girl paddling, 1933. Source: Jewish Museum Berlin © courtesy of

[1] See, for example, Susan A. Crane, ‘Choosing Not to Look: Representation, Repatriation, and Holocaust Atrocity Photography’, History and Theory 47 (2008): 309-330; Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All. Four Photographs from Auschwitz (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008); Deborah R. Staines, ‘Auschwitz and the Camera’, Mortality 1/7 (2002): 13-32;, Barbie Zelizer (ed.), Visual Culture and the Holocaust (London: The Athlone Press, 2001); Barbie Zelizer, Remembering to Forget. Holocaust Memory Through the Camera’s Eye (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1998)..

[2] Most notably, Marianne Hirsch’s work explores the intersections of family photographs, the Holocaust and memory. See Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory. Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

[3] Representative works include: Michael Meng, Shattered Spaces: Encountering Jewish Ruins in Postwar Germany and Poland (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2011) and Erica T. Lehrer, Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013).

[4] The concept of ‘orphan‘ or ‘found’ footage refers to ‘any film abandoned by its owner or creator’, including footage that has been left to decay and disintegrate. See Emily Cohen, ‘The Orphanista Manifesto: Orphan Films and the Politics of Reproduction’, American Anthropologist 106/4 (2004): 719-731. While it has been increasingly used in film studies, there has been little analysis of this phenomenon in photography studies criticism, except for Campt’s monograph. See Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012).