On the Other Side of the Camera: Contract Laborers in Namibia from 1897-1920

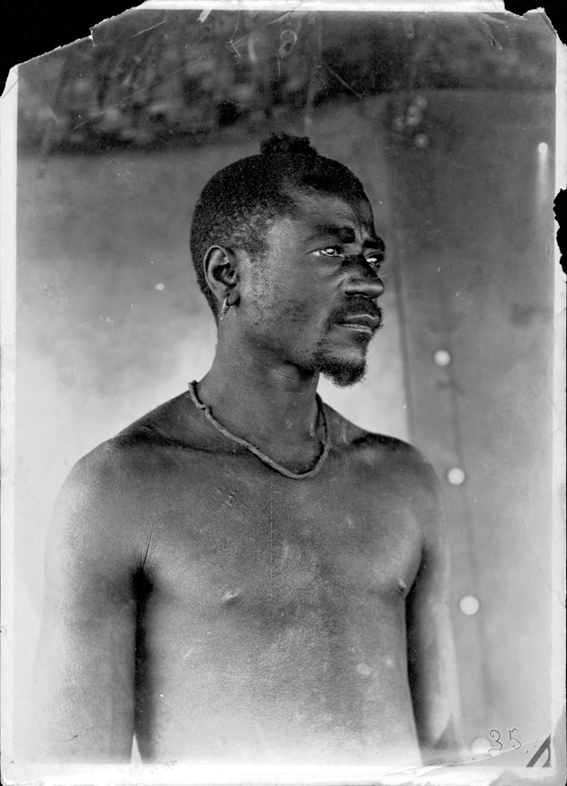

What caused the scars on this man’s chest?

Just, E., German South West Africa, ca 1910, Source: Africana Digital Collection, Gerald M. Kline Digital and Multimedia Center, MSU Libraries © with courtesy of

The photos displayed give a small view from the perspective of German colonizers into the lives of contract laborers in Namibia. While there has been a decent amount of research conducted on colonial and Apartheid Namibia, there remains an area that has not received sufficient scholarly attention and yet is central to the country’s past: contract labor up until 1920. This doctoral project at Humboldt University of Berlin looks to address this oversight by focusing on the experience of contract laborers in this period that encompasses not only the German colonial occupation but also the transition to early South African occupation. The laborers within the project’s scope primarily worked in diamond and copper mines, constructed the colonial railways and worked for the German military as ox-wagon drivers. During this time the workers were primarily, but not exclusively, Oshiwambo speakers from northern Namibia and Xhosa speakers from the current Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The project examines their perspectives and agency in work, social life and politics. Due to the fact that workers were marginalized by the colonial government and were often illiterate, only a small amount of writing by laborers can be found in archives. Therefore, to effectively pursue this research topic, it is essential to employ a variety of sources beyond written colonial records. These sources include: contemporary audio recordings, modern interviews and photographic sources.

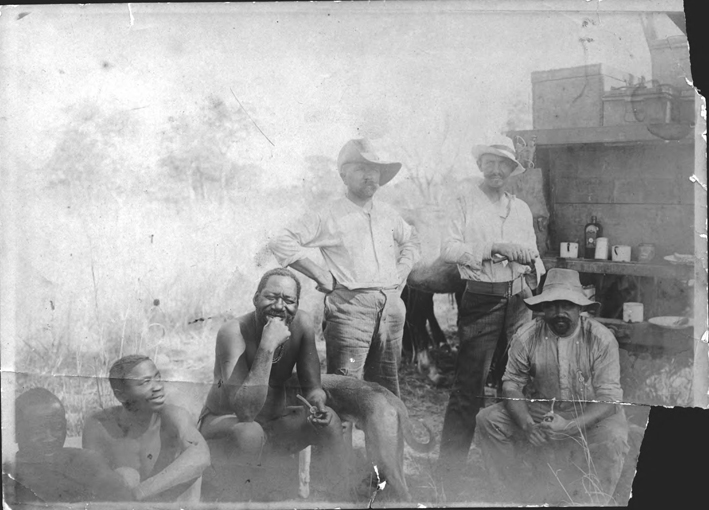

What does the body language between these men suggest about their relationship?

Just, E., German South West Africa, ca 1910, Source: Africana Digital Collection, Gerald M. Kline Digital and Multimedia Center, MSU Libraries © with courtesy of

One benefit of the photographic record from the German and early South African occupational periods in Namibia is that a large number of photographs were taken and are preserved to this day in archives.[1] Also remaining are photographs held by families that are gradually being shared with the academic community. While we know that photos were taken and frequently staged by the colonizers, a major challenge facing the project is deciphering the resulting decontextualization that was often planned by the photographers as well as considering what also what has occurred in the years since the photos were taken.

This decontextualization manifests itself in two primary categories: the first regarding the misrepresentation of African workers and the second in the way in which the photos were taken and preserved. There are several challenges that come from this first category, including the fact that these photographs are often captioned with inaccurate or misleading information for the African subjects. In addition there is no evidence that these subjects had any agency in the taking of the photos. The difficulties of the second category include the fac that original photographic collections are not always preserved. For example, many have been lost, or perhaps never had, original captioning which could have provided the dates and locations of the photos. This ambiguity inherent in so many photographs means that very little is known regarding colonial Namibian photographs’ background and it is up to scholars to recontextualize. Within the scope of this work, the process of recontextualization will rely on continuous cross-referencing with a variety of other sources.

What is the connection between these differently dressed people on the same train?

Diamantfelder, Güterzug Auf Brücke, p. personen, Source: Scientific Society Swakopmund (Incorporated Association not for Gain) © with courtesy of

The methodology will create a dialogue between photographs, written and recorded oral sources. The photographs will also be shared with interviewees because, as Tonkin’s work on oral history argues, historical photos can be an effective way to trigger memories.[2] This method has already been tested in a preliminary interview and the result was positive. It raised the quality of the interview while simultaneously adding context to the photographs from the perspective of modern Namibians.[3] While this does not replace having the voices of contemporary workers from the late 19th-early 20th century, it does provide the opportunity to compare and contrast modern interviews with the colonial interpretations of the period.

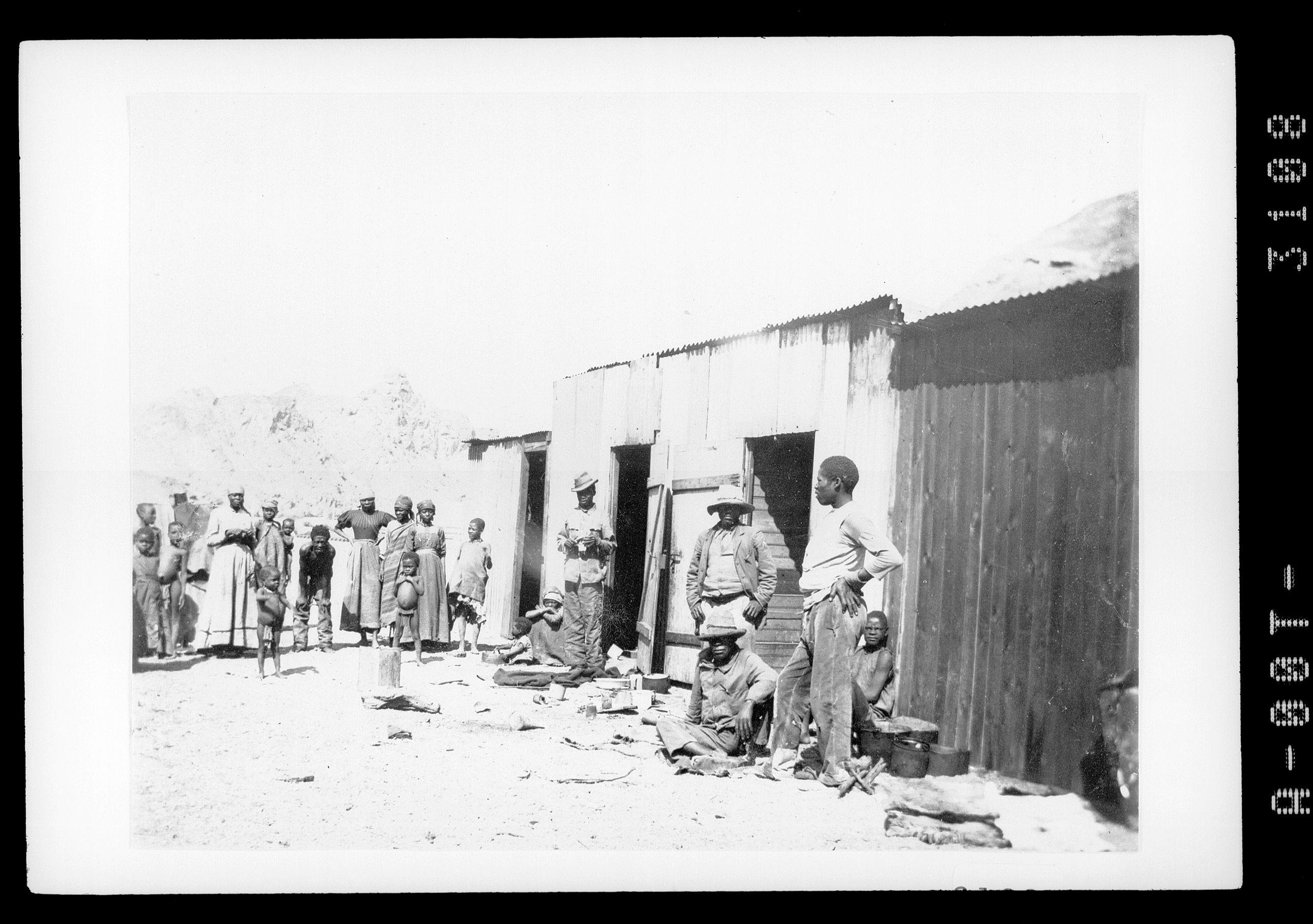

Why are these people gathered at these corrugated iron buildings?

Eisenbahnarbeiter, Source: Scientific Society Swakopmund (Incorporated Association not for Gain) © with courtesy of

This approach is part of a larger movement in Namibia of the last few decades to encourage direct contact between scholars and Namibians outside the academic field. For example, the national newspaper The Namibian ran a series titled Picturing the Past with the intention of both sharing historical photographs with readers and encouraging them to share information about the photos or who the subject(s) might be.[4] This ultimately led to additional contextualization of the colonial photographs that came directly from the formerly muted black majority. The process allowed historians access to more rounded interpretations of colonial photography and diminished the likelihood of reusing contemporary colonial captioning without critical engagement. This project contributes to this dialogue and aims to deepen knowledge of the little-known perspectives of contract laborers during the German and early South African occupation in Namibia.

[1] Wolfram Hartmann/Jeremy Silvester/Patricia Hayes (eds.), The Colonising Camera: Photographs in the Making of Namibian History, Cape Town/Athens 1999), p. 1.

[2] Elizabeth Tonkin, Narrating Our Pasts. The Social Construction of Oral History, Cambridge 1992, p. 94.

[3] Ilse Schatz, Interview of Ilse Schatz, 2017

[4] Patricia Hayes/Jeremy Silvester/Wolfram Hartmann, ‘“Picturing the Past” in Namibia: The Visual Archive and Its Energies’, in Refiguring the Archive, ed. by Carolyn Hamilton et al, Dordrecht2002, pp. 103-134 (p. 110).