Italian Colonialism in Visual Culture and Family Memory

The colonial enterprises of European states left behind many traces in their societies – not only in public, but also in family memories. In familial contexts, photographs, which were sent or brought home by soldiers or civilian colonists, played an important role in conveying – as supposedly authentic testimonies – imaginations about colonial realities, and about the idea(l) of ‘white’ supremacy. This hegemonic notion did not disappear together with the photographs once their protagonist, who had been in the colonies, had died. On the contrary, families often kept these photographs as mementos of their father’s and mother’s colonial ‘adventure’. In this respect, photographs did not simply circulate spatially, by travelling from the colonies to the European societies, but also in an intergenerational way from parents to children and grandchildren over the decades.

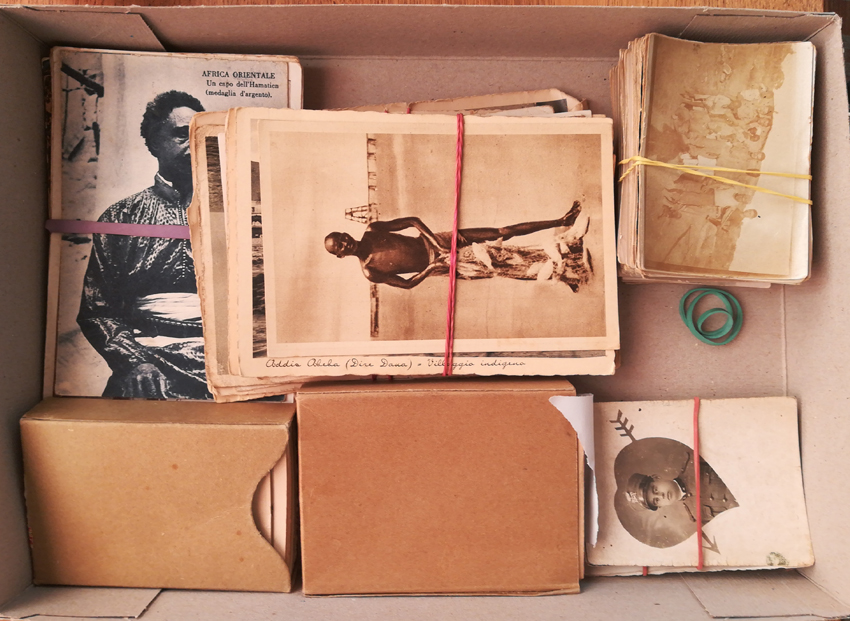

Through such exchange processes photographs became powerful references of a transnational cultural memory of colonialism, in which the imagination of Europe’s ‘white’ global dominance is embedded. Simultaneously, the intergenerational passing on of the photographs, e.g. due to the deaths of the colonial witnesses, often caused the loss of their historical contexts, because, within the families, they were often hidden or treated as a forbidden topic of discussion. Hence, these images of colonial violence and exotic-looking people, landscapes etc., found by the generation of children in the attics, basements and cupboards of their parents’ houses, frequently represent uncanny things for the families.

Photo box, Tiroler Archiv für photographische Kunst und Dokumentation (TAP), 236 Sammlung Siegfried Seppi

My current PhD research aims at decolonising visual colonial memories of families. For this purpose, my scholarship, first and foremost, situates photographs in their (often lost) historical context. That means that it explores private photographic practises (i.e. investigates processes of photo production, diffusion, and appropriation), their various entanglements with the colonial and fascist visual culture, and their participation in the construction and diffusion of colonial knowledge. Secondarily, it examines the place of colonial photographs in postwar family memory, by both analyzing their ritualization and the means by which they continue to impart colonial imaginations and attempting to subvert persisting traces of colonial hegemonic narratives within the families.

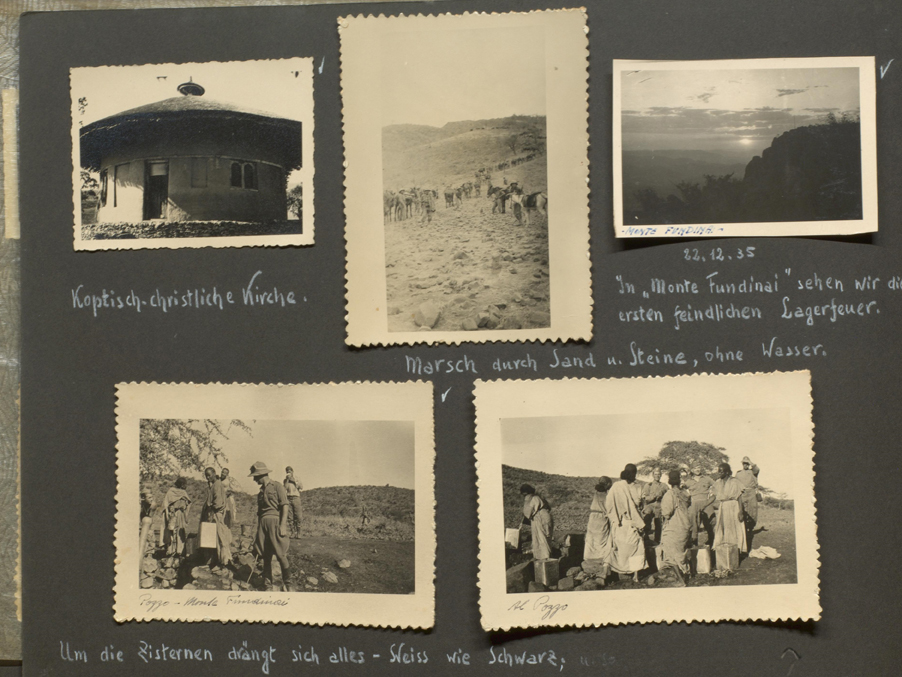

The colonial enterprise of fascist Italy against the Abyssinian Empire (1935-1941) serves as a case study for my research due to the favourable condition of historical sources. Following the emergence of private photographic practices during the First World War, in the interwar period the mass production of photo cameras transformed photography into a popular and everyday practise not only in Italy, but in Europe more generally. As a result of this development, in the Italo-Abyssinian War – for the first time in colonial history – a larger number of ordinary soldiers was equipped with photo cameras and, therefore, was able to produce their own visual memory.

Furthermore, compared to previous colonial enterprises of European states, the colonial propaganda activities of fascist Italy, including the intense usage of photography, were without parallel. The regime carried out immense image propaganda (including strict censorship) in order to produce and disseminate a uniform and homogenised idea of the conflict as a civilising mission among the soldiers in East Africa as well as among the Italian and European public. War crimes, violence, and death remained absent within this imaginary. However, this image-politics were subverted by amateur photographers who secretly photographed and illegally distributed photographs of both fallen Italian and Abyssinian soldiers and civilians, whereby violence also permeated private photo collections.

Photo album of Oskar Eisenkeil, Sheet 4, TAP 233 Sammlung Oskar Eisenkeil, L55589-L55593

Since the 1980s research has been carried out on the various entanglements between photography and the Italo-Abyssinian War, with a strong focus on the organisation, structure, and imaginary of the state’s visual propaganda. In recent years private photo practises have become objects of scholarly interest as well, especially as part of an attempt to differentiate between an official and private war imaginary, even though convincing theses on the photo production, distribution, and appropriation processes, as well as research on the connection between privately kept visual material and families’ colonial imaginations, are still lacking. Recent studies, however, have taken up the question of the relationship between Italian colonialism and Italy’s national identity.

Drawing on postcolonial theory and a transnational approach, my scholarship aims at deepening this discussion by focussing on the memory production of German-speaking soldiers (and, later, families) from the Italian province of Bolzano/Bozen. Considering these men as ‘Italianised’ colonisers, this study opens up questions of belonging and its performance via visual practises as well as offers the opportunity to make the ambivalences of colonial wars visible, since, in reality, there were no homogenous entities, such as the Italians or the Abyssinians, on either side. The photographic technique, however, was involved in creating and materialising such binaries by drawing on socio-cultural categories such as race, nation, ethnicity, gender etc.

My research draws on twenty private photo collections, which have been kept by families in the province of Bolzano/Bozen until today. After finding them via a public call, and ascertaining them, they have been digitalised by my project’s cooperation partner Tiroler Archiv für photographische Dokumentation und Kunst, a transnational archive which is based both in Italy and in Austria.

Situated at the intersection point between postcolonialism, visual culture, performance, and memory studies, my PhD thesis analyses the visual material by applying an interdisciplinary methodological approach. From the perspective of social history, it examines the photographs’ contexts of production and usage and the social actors involved therein, as well as their various cross-border relationships as German-speaking soldiers in Italy’s army in East Africa. Furthermore, influenced by cultural history and culture studies, it investigates private photo practise as a cultural practise, which supported construction and transfer of colonial knowledge between social groups (such as families) and geographical spaces. To this end, an image-based discourse analysis drawn from visual culture studies is helpful.

Zitation

Markus Wurzer, Italian Colonialism in Visual Culture and Family Memory, in: Visual History, 17.09.2018, https://visual-history.de/project/italian-colonialism-in-visual-culture-and-family-memory/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2741

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Copyright (c) 2018 Clio-online e.V. und Autor*in, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online Projekts „Visual-History“ und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber*in vorliegt.

Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <bartlitz@zzf-potsdam.de>