Soviet Sensuality – The exhibition „The Queue“. An Episode in Tartu’s Photo History

Järjekord. Üks episood Tartu fotoloost at the Tartu Art Museum – 5. November 2022 - 12. Februar 2023

Ain Protsin, “Girls from Supilinn”, ca. 1988. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist. © Indrek Grigor

Queuing as a quintessential experience of Soviet everyday life: hardly any other motif has shaped our images of the late Soviet Union as much as the long lines of people persevering in front of shops and grocery stores. Besides hopes of purchasing essential and rare goods, the social aspect of this practice was also important, as exemplified by Vladimir Sorokin’s 1983 novel “The Queue” surrealistically exploring interactions of people queuing for an unknown commodity, or Olga Grushin’s 2010 book “The Line”, which unfolds a Soviet family’s everyday longings, hopes and obsessions based on rumours about a concert by a famous exiled composer, and a street kiosk that may or may not have tickets on sale.

An ‘Exhibition of Deficits’

A similar motif is also the premise for “The Queue. An Episode in Tartu’s Photo History” at the Tartu Art Museum (Tartmus) that engages with a historical ‘exhibition of deficits’. The photo exhibition and competition “Woman in Photographic Art”, organised in five editions by the Tartu Photo Club in 1983, 1986, 1989, 1991 and 1993, stands out in Soviet photographic history not only because it was one of the most successful exhibitions in Tartu, but also because it promised something rarely seen in the Soviet public sphere: Woman as a social, aesthetic, and in particular nude subject of photographic art. In a film shown in the exhibition, former co-organiser Helju Kommer from the Tartu Cultural Centre recalls the enormous popularity of “Woman in Photographic Art” in 1989, the year of growing social protests and tentative political freedoms in the Estonian SSR, when the eponymous queue of visitors is said to have stretched across half the city centre: “There was an enormous number of people at the exhibition. It was a time when people came together because they wanted to support each other and see something new.”[1]

Exhibition view: The Queue. An Episode in Tartu’s Photo History. © Indrek Grigor

But “The Queue” is not just about Soviet public’s desire to experience the grey area between high-quality aesthetics and the morally indecent. Combining visual, material and oral history approaches, it also sheds light on the social function of Soviet amateur photo clubs, which by the 1980s had developed into a dense network for the exchange of photographic skills and ideas, and on the influence of political and economic liberalisation on Soviet cultural practices. As part of Tartmus’ exhibition project “Tartu 88” on underexplored material from the museum’s archives,[2] the exhibition organisers, led by curator Indrek Grigor, are pursuing a twofold objective: a critical recapitulation of “Woman in Photographic Art” based on exhibition objects, photographs, and interviews, as well as its broader contextualisation in Soviet and Estonian cultural history.

What answers did “Woman in Photographic Art” give to the manifold deficits it pointed to? Under which conditions was the exhibition organised, and how did it relate to the profound societal upheavals of the 1980s and early 1990s Estonia?

Exhibition view: The Queue. An Episode in Tartu’s Photo History. © Indrek Grigor

Sensuality under State Socialism

Today, only memories remain today of the legendary queue in Tartu. Nevertheless, “The Queue” manages to convey the former attraction of (nude) photography to present visitors in a rather witty way, as the poster advertising and opening the exhibition shows a pair of stylised pink breasts on a black background, from which a double ray reminiscent of the silhouettes of people standing in line extends upwards to the exhibition title. As this design and the following introductory texts in Estonian and English indicate, “Woman in Photographic Art” was a response to various deficits in Soviet society – in terms of visual aesthetics and photographic professionalism, perceptions of women in society, and publicly scorned eroticism. “Organising an exhibition around the theme of women demanded quite a lot of political manoeuvring,” the text explains both the public attraction and integration of social themes alongside portraits and nudes.

In 1976, the Estonian Photographer Peeter Tooming was awarded the FIAP gold medal while participating in the salon “Venus” in Krakow, Poland. The medal belongs to the collection of the Estonian Museum of Photography. © Indrek Grigor

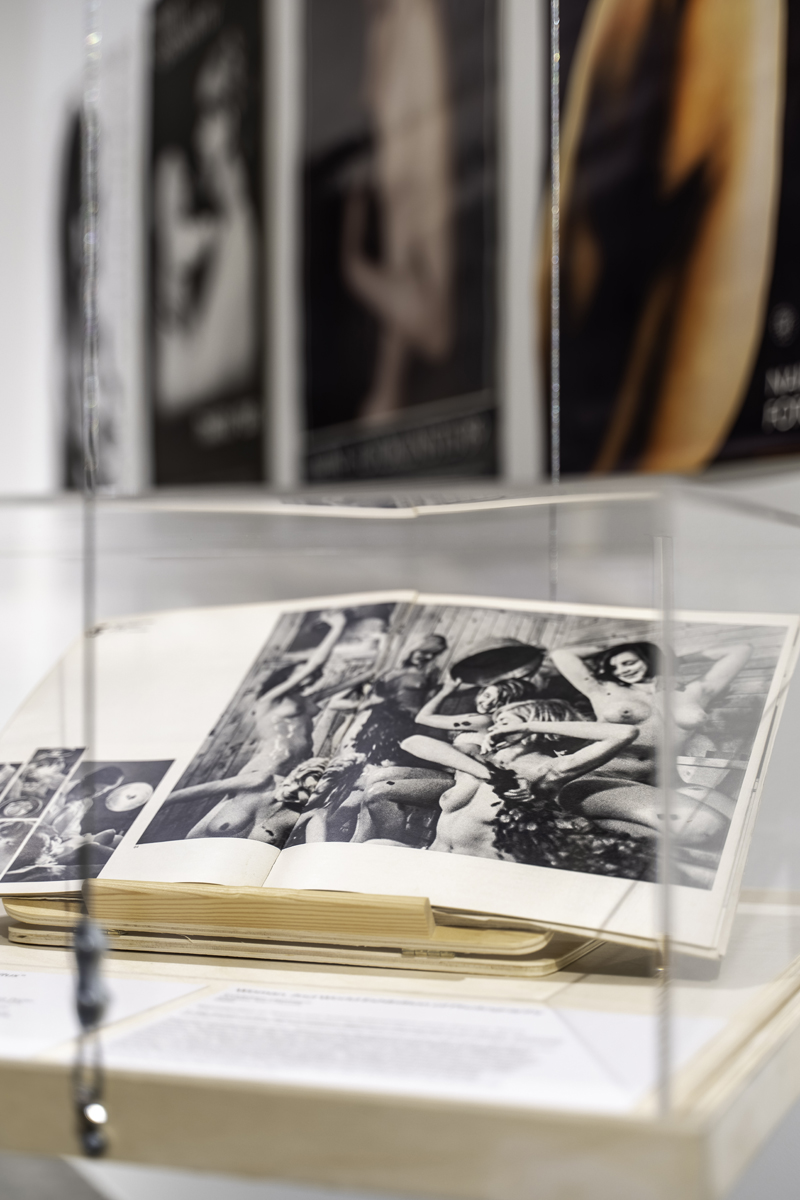

Spread from the exhibition catalogue “Woman. 2nd World Exhibition of Photography”, curated by Parl Pawek, 1968. Reproduction of Tatjana and Andrei Dobrovolski’s photo “Estonian sauna”. © Indrek Grigor

That an exhibition like “Women in Photographic Art” was rare but certainly not unique, is shown through photos, catalogues and quotes from reviews, which are assembled in a hanging showcase that explores similar exhibitions in socialist Eastern Europe on the themes of women and eroticism, like the international photo competition “Venus” held in Krakow since 1970. Similarly, works by Estonian photographers have also been exhibited in Yugoslavia, Hungary, the Latvian SSR, and even Austria. This naturally raises questions about the practical possibilities and limits of nude photography under state socialism.

The first room tries to answer these questions primarily through material objects: a second showcase, for instance, presents different memorabilia from the photo contests, such as diplomas, medals, and photos of the jury selection, which demonstrate that the yearning of Soviet amateur photographers for new visual impressions was not only an end in itself, but was closely linked to striving after international standards and recognition as a means for bearing up against both obscurity and censorship. But this approach was not always successful, as a photo by Jaan Künnap from 1989, showing a woman covered only by a black fabric loosely draped around her hips, demonstrates. The curator Valeri Parhomenko, the accompanying text informs, had tried to turn “Woman in Photographic Art” into a travelling exhibition, but the authorities cancelled this endeavour already after one day on its first stop in Moscow, possibly because of its provocative visuals.

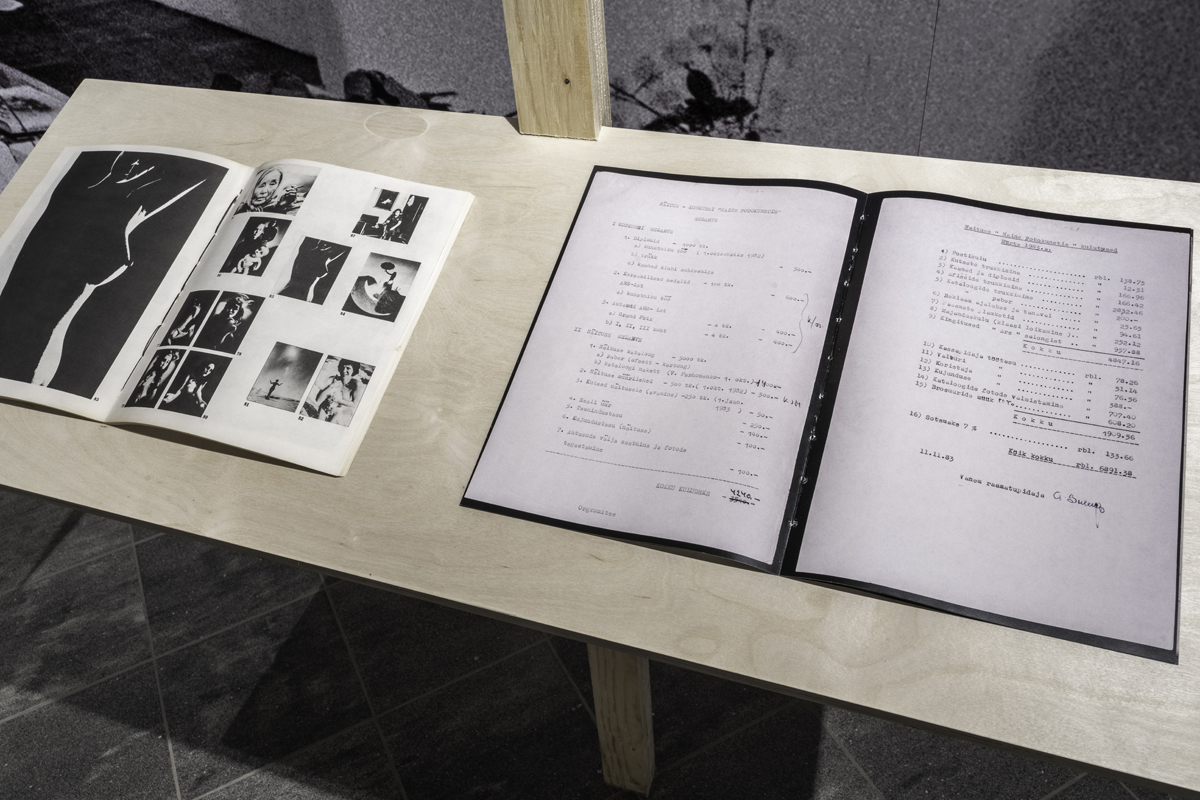

Exhibition catalogues and archival documents from the exhibition “Woman in Photographic Art”. © Indrek Grigor

Exhibition catalogues and archival documents from the exhibition “Woman in Photographic Art”. © Indrek Grigor

Still, the increasing liberalisation and internationalisation of the 1980s shaped “Women in Photographic Art”, as can be detected by leafing through the four exhibition catalogues and jury statements from the 1983, 1986, 1989 and 1991 editions, which are displayed on reading stands; a fascinating testimony to the political and social changes in Estonia during this period. It is therefore a pity that the exhibition does not offer further contextualisation: Too easily overlooked are the telling words of greeting in later catalogues, the poem by the Estonian Green Movement criticising environmental damage and political oppression in Estonian, German, English and Russian, or the somewhat clumsy advertisements seeking foreign investors as tourism and consumerism grew. It seems that by the late 1980s, nude photography and the female body had moved beyond mere eroticism and were increasingly linked with ideas of independence and liberalisation. More attention to such local manifestations of macro-level changes might have given even more substance to the claim of an ‘exhibition of deficits’ and the ways of addressing these.

Summer Woman, or Exposing the ‘Male Gaze’

That the visual representation of women in the historical exhibition was frequently approached through a distinctly ‘male gaze’ – not surprisingly, as the vast majority of photographers were men – becomes evident in the following room. On plain white walls, the images take centre stage, presenting a selection of predominantly monochrome series by Estonian photographers on the three exhibition themes of portraits, nudes and the social roles of women. Their artistic interpretation is centred on female ‘naturalness’: the popular, often eroticised motif of motherhood, self-confident young women with hats, cigarettes or leather gloves, or playful shots of a nude woman on a snowy beach. That the social theme, however, did not solely serve as a fig leaf for the political acceptance of the exhibition is shown by a series of photographs of life in a retirement home characterised by poverty and desolation, but also moments of togetherness, which won the artist Malev Toom a second gold medal at the 1986 exhibition.

Left: Ain Protsin, “Girls from Supilinn”, ca. 1988. Gelatin silver print. Curtesy of the artist. © Indrek Grigor; right: Arno Tameri, “Mannequin”, ca. 1980. Gelatin silver print. Estonian Museum of Photography © Indrek Grigor

Malev Toom, “Retirement Home”, ca. 1985. 2nd place medal social subject 1986. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the artist © Indrek Grigor

Left: Otto Kuus, “Nostalgia”, ca. 1985. Gelatin silver print, Estonian Museum of Photography. © Indrek Grigor; right: Otto Kuus, “In the Middle of Life”, ca. 1980. Gelatin silver print, Estonian Museum of Photography © Indrek Grigor

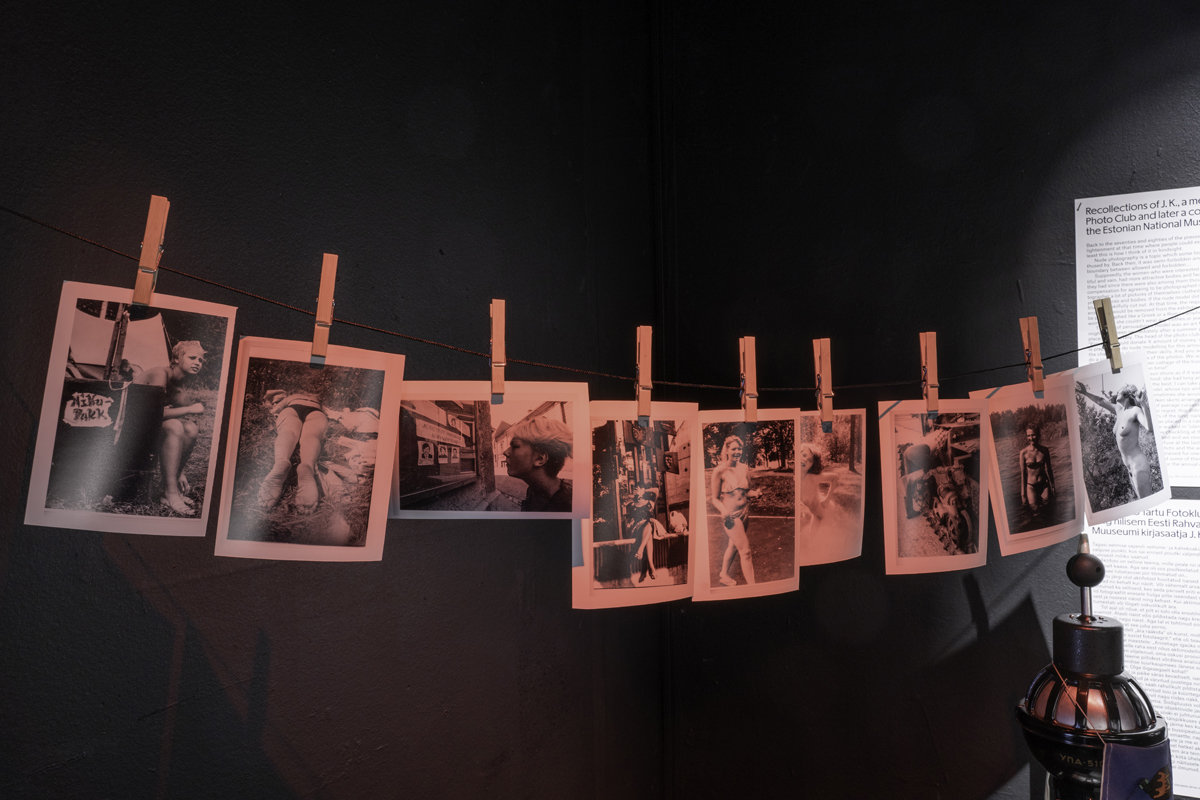

The third ‘room’, a walk-in box that roughly resembles a photo lab with black painted walls, picks up on the tensions between erotic photography and the Soviet public sphere introduced at the beginning. Objects and texts on different episodes besides “Woman in Photographic Art” address nude photography and images of the female body in society, as well as the eroticising perspective with which photographers often approached and staged their female models – sometimes walking a fine line between bodily aesthetics and visual exploitation. The first example is a cover photo of the Sunday edition of the Estonian-Soviet newspaper “Edasi” from 15 July 1984, showing three women in bikinis on a pier by a lake. At the time, it triggered a heated debate in the newspaper’s editorial office, but five years later the general mood had apparently changed enough for “Edasi” to boldly announce a public photo competition, titled “Summer Woman”. Not only does the advertising call reflect the ‘male gaze’ that already characterised “Woman in Photographic Art”, it also ironically establishes connection between the female body and political liberalisation: “We don’t know if we are ready to see women without ugly and uncomfortable Soviet undergarments, without the oppression of the everyday. Free. Natural.”

Photos sent to the photo competition “Summer Woman”, which was organised by the daily newspaper “Edasi” in 1989 © Indrek Grigor

Newspaper pages with snippets from this competition are complemented by a 10-minute film interview with journalist Raimu Hanson, the former picture editor of “Summer Woman”,[3] and a reminiscent text by a photographer, only identified as J.K., about the difficulties of recruiting young women as nude models in a country where eroticism was not only frowned upon as immoral and harmful to society, but could also lead to charges of pornography. It is particularly these little stories that make “The Queue” worth seeing, as they further problematise “Woman in Photographic Art” as an answer to visual and aesthetic deficits vis-à-vis the more basic allures of nude photography.

Rummaging Archives and Memories: the Role of Soviet Amateur Photo Clubs

This brings us to the position and agency of amateur photo clubs in the late Soviet Union. “The Queue” explores this through interviews with participating photographers and co-organisers of “Woman in Photographic Art”, combined into a 31-minute long film with English subtitles that concludes the exhibition.[4] These recollections not only add interesting – and often humorous – elements to the making of the historical exhibition itself, such as the not-quite-legal procurement of high-quality photo paper from the backdoor of a Leningrad photo factory warehouse. By including such memories, “The Queue” insightfully situates Soviet amateur photo clubs within a complex environment: on the one hand, photo clubs sought to establish photography as a serious and recognised art form in the eyes of the public and political authorities; on the other hand, the unofficial networking between the clubs reveals a fascinating circulation of photos, materials, professional support and ideas about photography that otherwise had no space for exchange.

The newspaper “Edasi”’s photo competition “Summer Woman”, with its relatively intact archive, reveals a moment in the history of Estonian media when every respectable publication had to publish a nude on its front cover © Indrek Grigor

Considering Jessica Werneke’s conclusion that Soviet photo clubs during the Thaw actively welcomed state regulation of their structures and activities “in order to advance their status within the hierarchy of Soviet culture”, “The Queue” demonstrates that this only to some extent held true for the 1980s. Although “Woman in Photographic Art” maintained a precept of professionalism through its submission criteria and the jury, the inclusion of the general public as recipients, and thus also indirectly as critics of the works displayed, was new. Another important difference was the conditions under which the photo clubs operated in the late 1980s compared to the Thaw, notably the exchange with international photographers – first from within, and increasingly also from beyond the Iron Curtain.

It is in the nature of exhibitions that not all questions can be answered. How, for example, did the Tartu Photo Club establish contacts with international photographers and partners? What kinds of links to broader processes of change lay behind the printing of the of the Estonian Green Movement protest poemin the 1989 exhibition catalogue? And how did the female models experience their public display through the lenses of mostly male photographers? These gaps do not make “The Queue” any less insightful: despite its overall simplicity, the exhibition is remarkably multi-layered, with its focus on visuals, objects and personal memories, and impressively demonstrates the agency of photography as a unifying medium, as well as ideological restrictions and their creative circumvention in the late Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.

“They fought and ran riot a lot,” Toomas Kalve, a former member of the Tartu Photo Club, describes the organisers of “Woman in Photographic Art” in the concluding film. Their efforts not only introduced Soviet visitors to new visual impressions. The rich material that forms the basis of this small but admirable exhibition also adds some compelling insights to our existing knowledge of photographic culture and gendered representations of women before and during Perestroika.[6] And last but not least, with its local focus it also contributes to a much-needed decentralisation of Soviet historiography.

The exhibition “The Queue. An Episode in Tartu’s Photo History / Järjekord. Üks episood Tartu fotoloost” is on display at the Tartu Art Museum, Raekoja plats 18, 51004 Tartu, Estonia, from 5 November 2022 to 12 February 2023. More information: https://tartmus.ee/en/exhibition/the-queue-an-episode-in-tartus-photo-history/.

An exhibition publication with articles by Alise Tifentale, Adam Mazur and Indrek Grigor is forthcoming: Grigor, Indrek, ed. The Queue. An Episode in Tartu’s Photo History, Tartu 2023.

[1] Järjekord (The Queue). Interviews, 31 min., Tartu Art Museum, https://youtu.be/iWSaaUaqGZo [01.02.2023].

[2] Tartu 88. Tartu Art Museum, https://tartmus.ee/en/appi/tartu-88-2/ [01.02.2023].

[3] Suvenaine (Summer Woman). Interview with Raimu Hanson, 10 min., Tartu Art Museum, https://youtu.be/A2aIKn8vKyA [01.02.2023].

[4] Järjekord (The Queue).

[5] Jessica Werneke, “’Nobody understands what is beautiful and what is not’: Governing Soviet Amateur Photography, Photography Clubs and the Journal Sovetskoe Foto.” Photography and Culture 12:1 (2019), pp. 47-68, here 64.

[6] See, for example, Ashwin, Sarah. Gender, State and Society in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. London: Routledge, 2000, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203135730; Neumaier, Diane, ed. Beyond Memory: Soviet Nonconformist Photography and Photo-Related Works of Art. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004; Turkina, Olesya. “Underground Visual Arts: Photography, Film, Photo-Based Conceptualism.” The Oxford Handbook of Soviet Underground Culture, edited by Mark Lipovetsky, Ilja Kukuj, Tomáš Glanc, Maria Engström, and Klavdia Smola. Online edition, Oxford: Oxford Academic, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197508213.013.33

Zitation

Anna Derksen, Soviet Sensuality – The exhibition „The Queue“. An Episode in Tartu’s Photo History. Järjekord. Üks episood Tartu fotoloost at the Tartu Art Museum – 5. November 2022 – 12. Februar 2023, in: Visual History, 09.02.2023, https://visual-history.de/2023/02/09/derksen-soviet-sensuality-the-exhibition-the-queue/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2462

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0. Eine Nutzung ist auch für kommerzielle Zwecke in Auszügen oder abgeänderter Form unter Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/