Forced Labour 1940

An Online Exhibition

Over recent years, several private photos of the persecution of the Hungarian Jews have been made accessible to the public online. However, due to the lack of historical context and basic metadata, these photographs remain difficult to trace.[1] This problem is particularly significant for international researchers without knowledge of Hungarian.

In 2020, I started examining ways to design and develop online exhibitions, and this short essay outlines the process and results: the online gallery “Forced Labour, Hungary 1940”. The aim of this project was to present and contextualise one small collection of family materials – two photo albums and a diary – to make them accessible for a broader, international public.

Photographer: Ervin Szántó. A group of forced labourers wearing tricolour armbands with family members. The photo was taken

in the internment camp outside Budapest, in September 1940. Source: Gwen Jones: Forced Labour, Hungary 1940,

https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/19 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

What You Don’t See – Behind the Photos

From 1938 onwards, a series of anti-Jewish laws and decrees – based on and in some cases exceeding the Nuremberg Laws – gradually excluded those defined as Jews from political, economic, and social life. Yet at the same time as the Hungarian army began preparing its attack on the Soviet Union, the institution of Jewish forced labour was introduced not to prioritise national defence or military efficiency. Rather, it was a means to conscript “untrustworthy elements” in unarmed auxiliary roles so that the authorities could keep an eye on and take advantage of Jews, Communists, and national minorities. As part of the general mobilisation and armament drive, forced labourers worked on building and maintaining roads and airports, draining marshes, deforestation, canalisation, and unloading railway goods wagons. Moreover, Jewish forced labourers also provided a skilled workforce that could resolve the army’s dire shortage of doctors, engineers, pharmacists, veterinarians, and drivers.

In 1940, Jews on forced labour service were still allowed to use cameras. This changed in 1941, when Hungary officially joined the war and Jews on forced labour service lost their right to uniform and military rank. By 1942, forced labour for all Jewish men aged 24-33 was obligatory. Units were sent to the Eastern Front, and cameras were confiscated at the border, which is why very few photographs of the c. 50,000 Jewish forced labourers from this period remain. By the time of the Red Army’s victory at the River Don in January 1943, around 40-43,000 forced labourers had died or fallen into Soviet captivity.

Open Sources and Uses

In 2020, a selection of the Szántó brothers’ photos were published on Fortepan, a Hungarian image repository with over 180,000 photographs available to browse and download in high resolution for any purpose, free of charge. Dispensing with restrictions, permissions, and fees, Fortepan is a community-based project that makes available a far broader and richer collection of images than traditional archival institutions in Hungary, such as the national museum. Fortepan photos are published together with the year, location, and name of the donor. A team of volunteers supplements this basic information with keywords and a brief description, wherever possible.[3] For international visitors to the site, the story and characters behind the photos may or may not be easily accessible, and even with the use of well-known translation software tools, the linguistic barrier and minimal metadata can be difficult to surmount.

For instance, if we take the example of forced labour, a search for the Hungarian term “munkaszolgálatos” (forced labourer) yields 274 images from 1940 to 1944. A search for “labor service” on the English-language site yields 227 photos from the same timescale. A search for “forced labour” returns no results. In either case, most of the search results originate from 1940 and 1941.

Forced labourers wearing yellow Star of David armbands in 1941, Novi Sad (today in Serbia). Photographer: unknown.

Source: Fortepan, https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/507 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

In early 2020, I was in the Fortepan office in Budapest as the editor, Miklós Tamási, was examining the Szántó brothers’ photo albums. Somewhat later, during the first of many lockdowns and hiatuses in freelance work, I decided to piece together the brothers’ story using the photo albums, maps, the brothers’ diaries as well as my existing knowledge of the Hungarian forced labour system. I wanted to explore how to describe the images and present them together with text. I also wanted to make sure this was accessible – as far as possible – for the visually impaired by providing “alt-text” image description, and to put the lockdown to good use in “learning by doing” a new piece of software.

Prior to receiving István’s permission to use the images and diary, I tried to find out what is technically possible for one individual to create – with lots of free time thanks to Covid but without institutional resources. The first big decision concerned the right tools for the task. Since purchasing commercial archival description software wasn’t an option for me, the choice was between two free, open source packages, AtoM and Collective Access (CA). Eventually, I opted for the latter for its backend customisability, active online support forum, and advanced capacity for multilingual description.

Having selected the images I wanted and written the first round of photo descriptions in English, I made contact with Dr István Szántó, Endre’s son. He sent me the text of his father’s diary as well as family photos and documents. During one of our telephone conversations, he told me “we always knew who we are.” This means that the family never concealed or denied their Jewishness, a path taken by many Jewish families who preferred not to talk about their wartime experiences at home. After the war, Endre chose never to tell his three children about his and Ervin’s experience of forced labour.

Endre’s Kodak Retina camera. Photographer Unknown. Source: István Szántó CC BY-NC-ND

Image 3b: Endre, Ervin and their mother in 1937. Photographer: György Szántó photo studio,

Budapest. Source: Gwen Jones: Forced Labour, Hungary 1940,

https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/569 [10.07.2023] CC BY-NC-ND

Each photo is catalogued and described in English, Hungarian, and German using the standard Dublin Core metadata fields: title, date of creation, geolocation, short historical context, “alt text” for the visually impaired, image format (landscape/portrait, black & white/colour), rights, creator, publisher, who is depicted in the picture, and keywords. The information in these fields originated from three sources: 1. the scanned photo albums – in which both brothers captioned their pictures and added dates, places, and the occasional remark; 2. information from Endre’s diary; and 3. online research mostly using mapping tools and image searches.

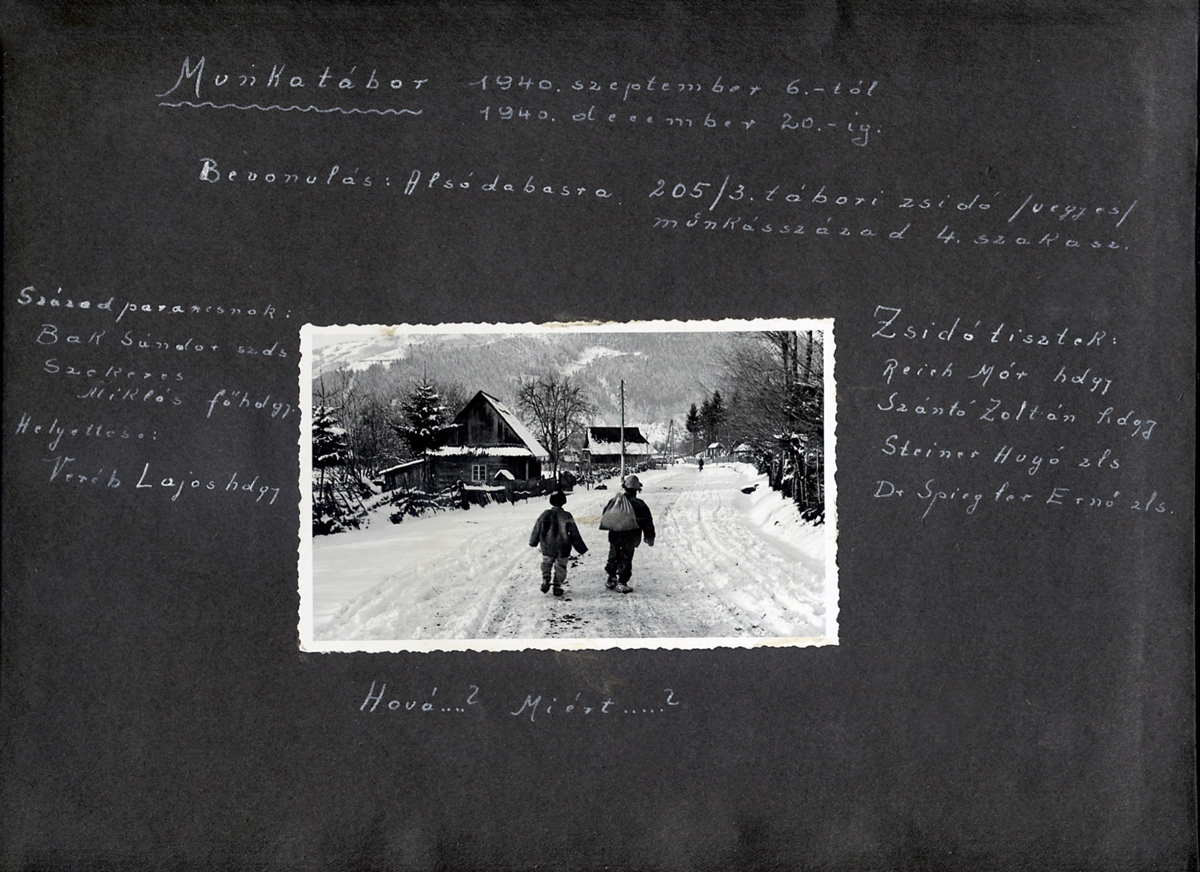

First page of Ervin Szántó’s album. He notes the dates, the name of his company, and the names of captains as well as the Jewish officers.

Underneath the photo of the two boys walking along a snowy village road, he wrote: “Where to? … Why ?…” Source: István Szántó CC BY-NC-ND

The chronologies were relatively straightforward to ascertain, since both brothers noted the dates of the various stages of their ordeals. They spent around six weeks together at the internment camp in Kisdabas (today Dabas), around 30 kilometres south-west of Budapest, before being sent separately to various locations in Maramureș county.

Photographer: Endre Szántó: In the internment camp, September 1940, Kisdabas (today Dabas), Hungary. Source: Gwen Jones:

Forced Labour, Hungary 1940, https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/78 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

Photographer: Endre Szántó: Ervin in his kit, October 6 1940,

Kisdabas (today Dabas), Hungary. Source: Gwen Jones: Forced Labour, Hungary 1940,

https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/199 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

Since the brothers and their units spent most of their time in remote locations, they often had only a vague idea of their whereabouts. Using the photo captions and Endre’s diary, I managed to identify all the areas where they spent time with greater or lesser degrees of accuracy. CollectiveAccess (CA) allows for geolocation to the precise longitude and latitude, as in the case of the supplementary image below, where location metadata was included on Fortepan, as well as the insertion of a radius around the presumed location. This research process also relied heavily on the use of OpenStreetMap, Google Maps, and Google Earth, as well as image searches for a given location for the purposes of comparison.

Photographer: Ervin Szántó: Haircut in the forest, November 1940, taken somewhere

between Borșa and Prislop (Transylvania). Source: Gwen Jones: Forced Labour, Hungary 1940,

https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/51 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

Problem Solving

Adding keywords took place towards the end of the description process once I was certain of the photos’ recurring features and had a better overview of what themes might be of interest to others. One problem arose when creating the front end of the website. CollectiveAccess placed Hungarian keywords beginning with accented vowels – á for állat (animal) and é for étkezés (eating) – at the end of the alphabetical list, after zsinagóga (synagogue). To bypass hours of fiddling, I chose to use the terms haszonállat (farm animal) and ebédidő (lunchtime) instead. Less satisfactory is the software’s inability to handle the Hungarian year-month-day date format. Having combed the comprehensive documentation and online support forum for help, CollectiveAccess added this shortcoming to their “to-do” list. As a result, dates in the Hungarian version of my site are rendered in English for the time being.

Photographer: Ervin Szántó: Forced labourers pulling a cart, October 1940, in the vicinity of Vișeu de Sus (Transylvania). Source: Gwen Jones:

Forced Labour, Hungary 1940, https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/38 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

Photographer: Endre Szántó: Forced labourers shelling peas in the internment camp at Dabas just outside Budapest, October 1940,

Source: Gwen Jones: Forced Labour, Hungary 1940, https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/154 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

Images and Words

I wanted a clean interface that included space for longer texts. The essay on Endre Szántó’s diary was the most difficult and most enjoyable piece of writing in the whole project. István Szántó sent a Word document of his father’s diary that is over 35,000 words long; it is a detailed, reflective and in places shocking document of one man’s struggle to retain his sanity in unbearable – and often unbearably stupid – circumstances. Since Endre’s younger brother Ervin died aged 31 on forced labour service in Ukraine in 1942, Endre inevitably became the narrator and moral anchor of the entire story. His dry humour and dignity in the face of systematic degradation speak for themselves; I quoted him verbatim and did not “update” his 1940s Hungarian or “correct” any idiosyncrasies in the text.

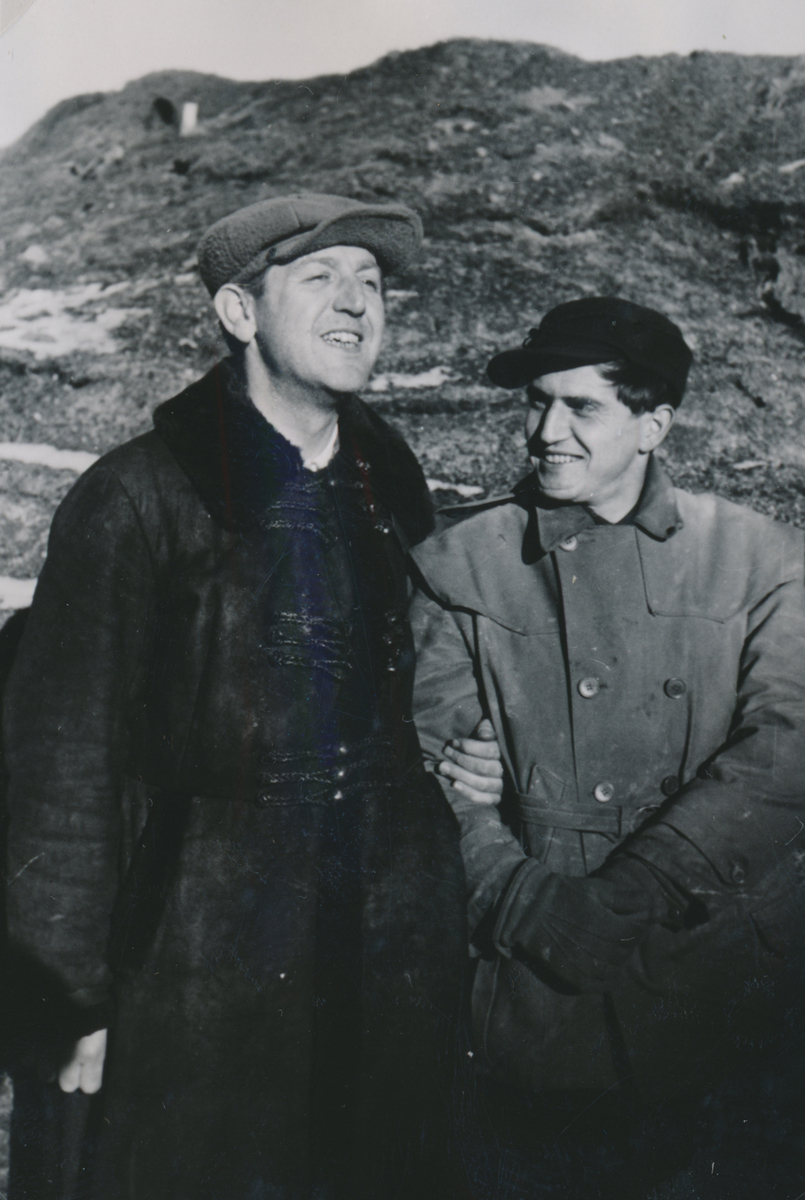

Photographer: Endre Szántó: Endre (on the left) and his friend, above Borșa

(Transylvania), November 25 1940, Source: Gwen Jones: Forced Labour, Hungary 1940,

https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/421 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

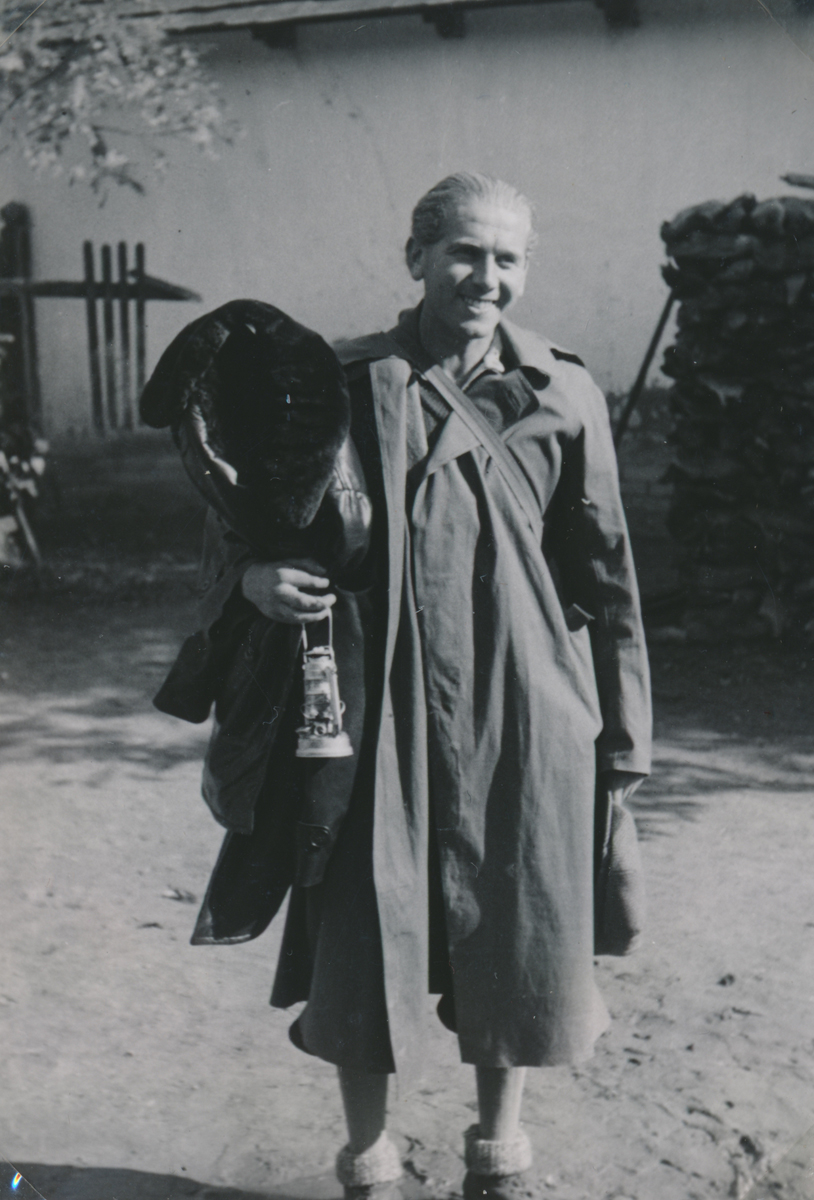

Photographer: Endre Szántó: Endre’s hosts upon arrival in Transylvania, October 15 1940, in Borșa (Transylvania). Source:

Gwen Jones: Forced Labour, Hungary 1940, https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/index.php/Detail/objects/247 [10.07.2023] CC-BY-SA-3.0

The Result, and the Future

The homepage incorporates a slideshow of images and a brief introduction. The site has a description of the project, an essay on the main themes of Endre’s diary, a condensed history of Hungarian Jewish forced labour including supplementary images from Fortepan, a short biographical text on the two brothers, a map which shows the various locations of internment just outside Budapest and forced labour in Maramureș county, northern Transylvania. Furthermore, the page includes a browse section where photos can be filtered by photographer, keyword, and location, as well as six curated galleries. The site is fully trilingual and functions in English, Hungarian, and German.

Inspired in large part by Radu Jude’s 2022 silent short film “Memories from the Eastern Front”[5] I plan on further developing the project by incorporating correspondence and other documents on the part of the political and military authorities. CollectiveAccess allows for the creation of a full-screen slideshow, which could contrast the Szántó brothers’ photos with quotations from the authorities in a slow, film-like presentation, whose horizontal “flow” can be paused at any time by the viewer to go “deeper” into the documents behind the story.

Forced Labour, Hungary 1940

Online Exhibition of around 150 photos taken by Dr Endre Szántó (1908-1989) and his brother Ervin Szántó (1911-1942), curated by Dr. Gwen Jones

https://gwenjones.de/forcedlabour/ [10.07.2023]

[1] See, for example, holokausztfoto.hu and https://fortepan.hu/ [10.07.2023].

[2] Dr. Szántó Endre munkaszolgálatos naplója, Budapest: Dr. István Szántó, 2010.

[3] Fortepan’s Hungarian-language mailing list regularly introduces the latest batch of photos upon publication. Weekly articles in Hungarian are also published on the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center’s devoted Fortepan blog, whose posts are sporadically translated into English.

[4] QGIS is an open source geospatial application: https://qgis.org/de/site/ [15.06.2023]; Open Street Map is an open source geographic database maintained by volunteers, whose topographic map is referred to here as OSM topography, https://www.openstreetmap.org/ [10.07.2023].

[5] See also Svea Hammerle, Amintiri de pe Frontul de Est/ Erinnerungen an die Ostfront. Ein Fotoalbum als Stummfilm in den Berlinale Shorts, in: Zeitgeschichte-online, Februar 2022, URL: https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/film/amintiri-de-pe-frontul-de-est-erinnerungen-die-ostfront [10.07.2023].

Zitation

Gwen Jones, Forced Labour 1940. An Online Exhibition, in: Visual History, 10.07.2023, https://visual-history.de/2023/07/10/jones-forced-labour-1940/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2613

Link zur PDF-Datei

Copyright (c) 2023 Clio-online e.V. und Autor, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online-Projekts Visual-History und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber:innen vorliegt.

Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <bartlitz@zzf-potsdam.de>