Historicizing Personal Identification and its Implication for Pandemic Response

A Case Study of ID Photographs in Twentieth-Century Japan

Secure and precise personal identification is essential for the continuation of socioeconomic activities during a pandemic. In Japan, the main region of focus for this research, this became even clearer between 2020 and 2021 when multiple cases of online fraud involving identity theft took place, including a series of document forgery to receive a financial relief package and taking online job tests for someone else. When the next pandemic and the next lockdown come in the future, our society needs to be better prepared to face this challenge of continuing life under severely restricted in-person communication.

While there are various means of identification in our society today, such as fingerprints, PINs and passwords, identification by means of a photo ID is one of the most commonly used methods. Even with the emergence of new technologies such as facial recognition, ID cards with portrait photographs still play an important role as they have already achieved a wide social acceptance and they are relatively cheap to produce or obtain. This trend is unlikely to change when a next pandemic compels us to replace face to face contacts with online interactions. Learning how portrait photographs have functioned in the context of personal identification, therefore, has policy relevance in our contemporary world in addition to being an intriguing subject of study in the field of visual history.

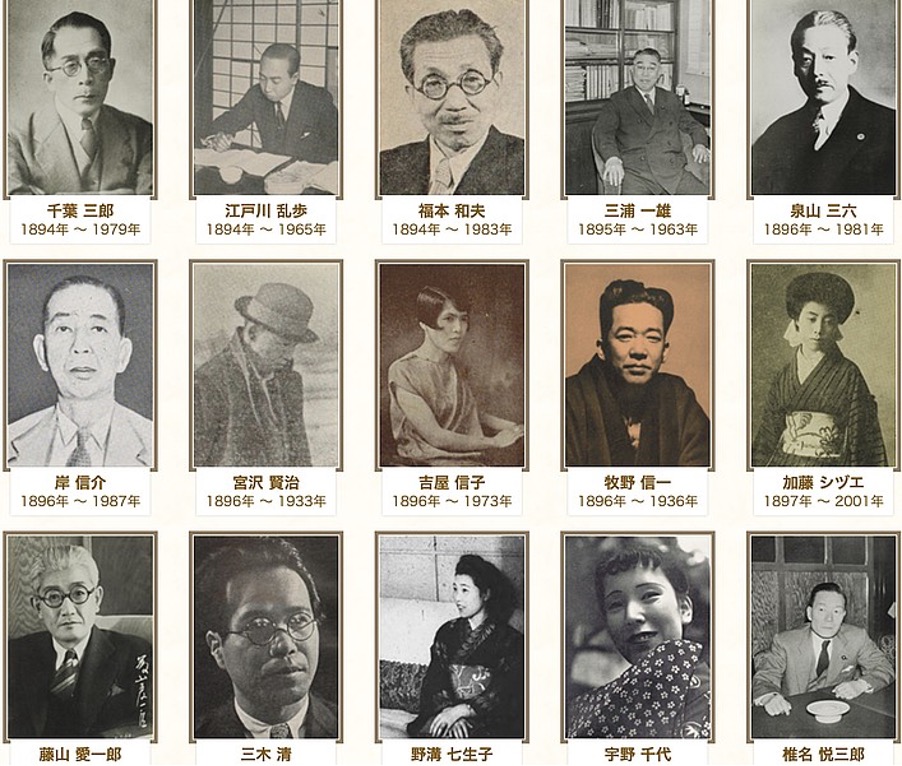

In order to gain historical insight into this issue, this study conducts a historical analysis of the policy debates and public discourses over the spread of personal identification technologies through a case study of ID photographs in 20th century Japan (see photograph 1). Through the examination of its emergence, public responses, and format standardization of ID photos, the project aims to better understand the background of its social acceptance and its relationship with privacy concerns.

Photograph 1: Examples of Japanese people’s portrait photos. Screenshot created from the website of the Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures, National Diet Library, Japan. Retrieved from https://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/ [25.07.2023].

1. How did people discuss ID photos’ spread in 20th century Japan?

This question will be explored through the analysis of popular discourse on print media. Even though the amount of written material – newspaper articles, letters etc. – revealed in the preliminary research was lower than expected, the problems arising from the impossibility of perfect identification of individuals became clear in these sources. Reports on fraudsters sitting in for license exams for someone else, financial transactions, or labor contracts abounded throughout the 20th century, and technological developments in photographs never seemed to sufficiently prevent a proxy person slipping through official security measures. But the authors of relevant articles usually assumed and accepted the existence of “paperchase” between the state and the people. The project aims to explore how this process unfolded in different parts of the country.

2. What social infrastructure and legal institutions enabled the spread of ID photos?

Commercial photo studios, beginning in 1862 in Nagasaki by a Japanese photographer Ueno Hikoma, spread across Japan by the end of the 19th century. How, then was this related to the spread of personal portraits for other purposes rather than the recording of daily lives? To what extent did these commercial photo studios, which took family portraits as the main business, serve as the infrastructure for the regime of state-led identification that required mass-scale production of ID photos?

3. What contributed to the extreme standardization of faces on ID photos in the late 20th century?

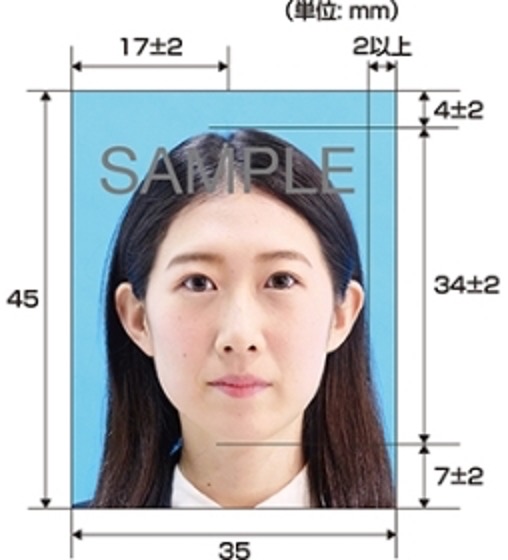

Today, highly regimented portrait photos have become the norm for official travel documents and personal IDs (photograph 2).

Photograph 2: A sample photograph for a passport. Source: Japanese ministry of foreign affairs,

https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/toko/passport/ic_photo.html [25.07.2023]

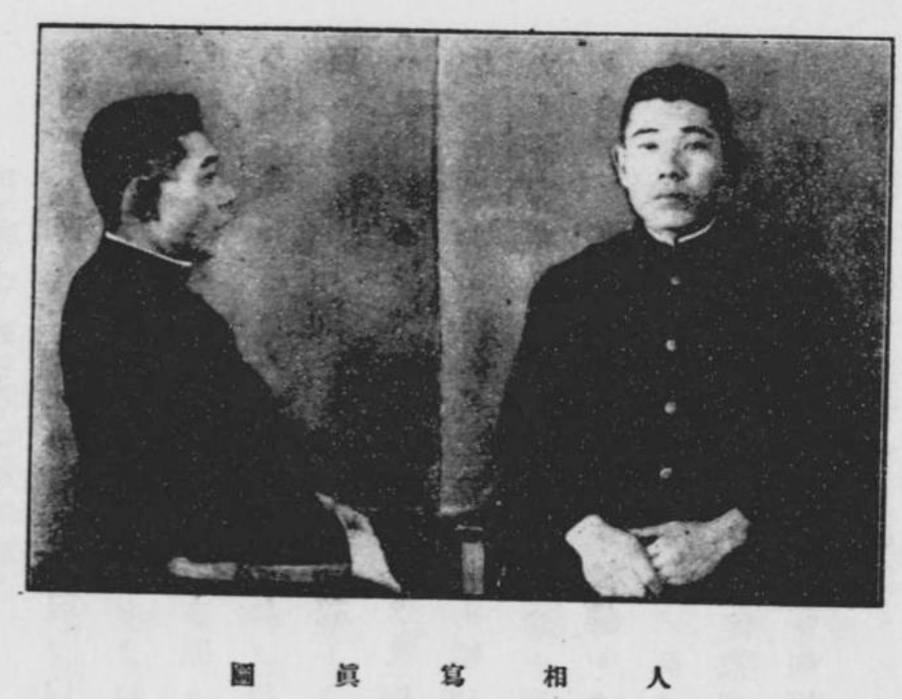

Photograph 3: An example of personal photographs for policing purposes: Hōrai Masayoshi,

Keisatsu Shashinjutsu (in: Kenpei renshūsho gakuyūkai, 1929, p. 47)

Overall, the project will aim to understand what lessons we can draw from the experiences of state authorities using photographs to identify individuals. Is a flawless identification impossible to achieve? If so, what kind of identification regime can better strike a balance between rigorousness against fraud while paying attention to individuals’ privacy concerns?

The project forms part of JST’s[2] research area “Social and technological framework for pandemic resilience”, launched in 2021. This research area aims to create a social and technological framework for a pandemic-resilient society and develop a network of researchers, whose cross-disciplinary approaches may be mobilised in an emergency. This project builds on the PI’s previous third-party-funded project, “Cross-border mobility and documentary identification in Japan in the age of global networking,” funded by Baden-Württemberg Stiftung Eliteprogramm (2019-2021), which investigated the gap between the law and the reality of border-crossing across the Japanese empire in the late 19th and early 20th century.

“Historicizing personal identification” started in October 2022 with a duration of three and half years.

[1] Alfonso Bertillon worked in Paris Metropolitan Police in the 1880s and invented a method of anthropometrics, namely the measurement of body parts to identify an individual, to tackle a growing number of crimes and a large influx of people into the urban center. Anthropometrics was widely adopted and used across the world from the mid-1880s to identify criminals with existing records. In terms of photographs, Bertillon developed a standardized format for portrait photographs of arrested individuals as shown in Photograph 3, in an attempt to utilize visual images for criminal identification. For more on Bertillon, see: Simon Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification, Cambridge, MA, 2002, pp. 32-57.

[2] JST is Japan’s national research and development agency and plays a central role in the government’s Science, Technology and Innovation Basic Plan.

Zitation

Takahiro Yamamoto, Historicizing Personal Identification and its Implication for Pandemic Response. A Case Study of ID Photographs in Twentieth-Century Japan, in: Visual History, 25.07.2023, https://visual-history.de/project/historicizing-personal-identification-and-its-implication-for-pandemic-response/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2615

Link zur PDF-Datei

Nutzungsbedingungen für diesen Artikel

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz CC BY-SA 4.0. Eine Nutzung ist auch für kommerzielle Zwecke in Auszügen oder abgeänderter Form unter Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/